Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

In South Africa, two to three rhinos are killed by poachers every day. But there are pockets of hope—Holly Tuppen went to meet some of the brave individuals leading the charge.

If Thembinkosi

has seen this all before, he’s not letting it dampen his enthusiasm.

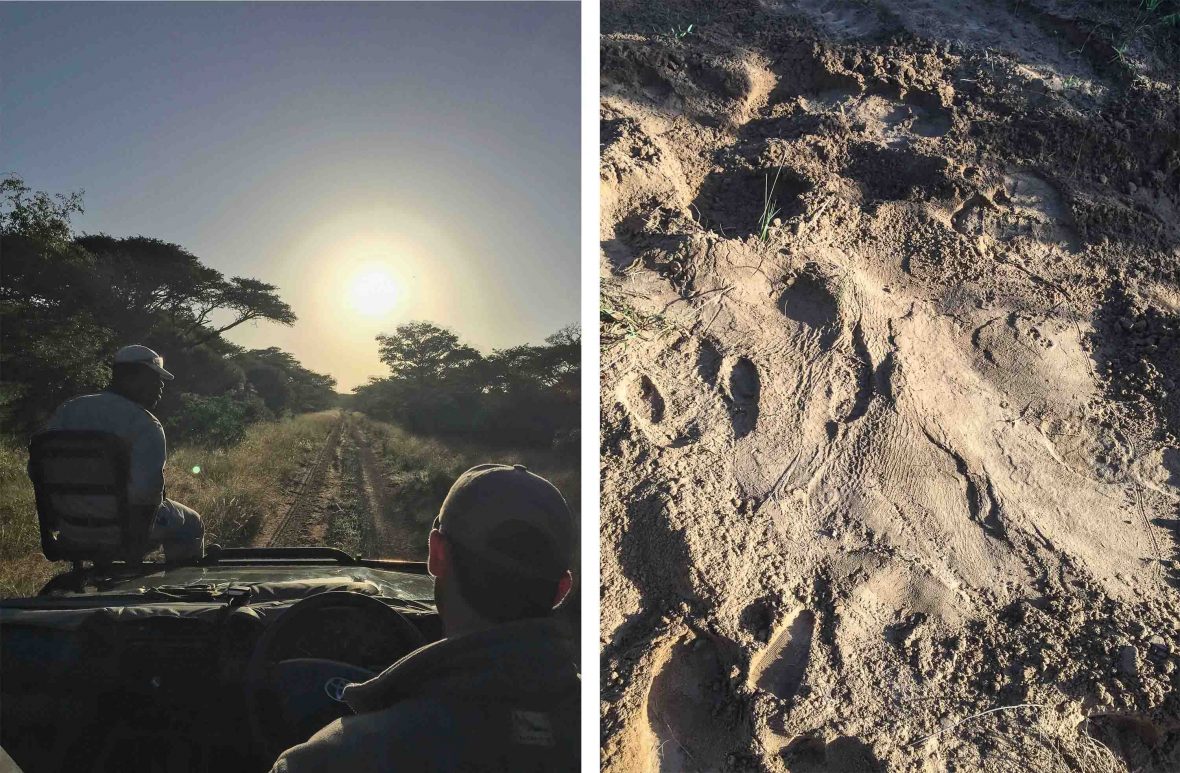

“Look, in the sand,” he tells me. I do. It looks as if hundreds of little worms have wriggled and writhed the night away on a 30-centimeter patch of sand below our feet. “A rhino rolling on his back, probably this morning.” I run my hand over the marks, entranced.

Four of us have been tracking rhinos on foot since sunrise at Phinda Private Game Reserve, a 70,560-acre reserve in KwaZulu-Natal where seven ecosystems collide, hosting everything from crocs to cheetahs. Watching Thembinkosi (aka Mr T, assistant head tracker) at work is mesmerizing. He picks out our path, following where the rhinos have been chomping on grass, breaking branches, and even offloading on a midden, a communal pile of rhino dung that functions like ‘rhino Facebook’—spreading rhino gossip.

After nearly two hours, Thembinkosi’s hand shoots up, and we all stop in our tracks. The atmosphere changes and adrenaline rises.

Less than 10 meters from where we stand are two huge rhino bulls. They’ve heard us approach, ears spinning and back legs crunching on branches in the thick bush.

RELATED: Could this be Malawi’s next Big Five destination?

Having watched with bated breath for 10 minutes, we slowly retreat. The first thing that strikes me is how formidable these creatures are—gentle, yet powerful. The second is how desperate anyone would have to be to kill them for profit.

On Monday 25th March 2019, two weeks after my rhino encounter, a Durban magistrate convicted three men of shooting a rhino. When they were arrested in 2009, they were found with a rifle, blood-soaked axes, and a pair of rhino horns in the back of their pick-up truck. The men delayed their trial by 10 years after dismissing and employing up to 25 defense lawyers. It sounds unbelievable, but for those working in conservation in South Africa, it’s a common frustration.

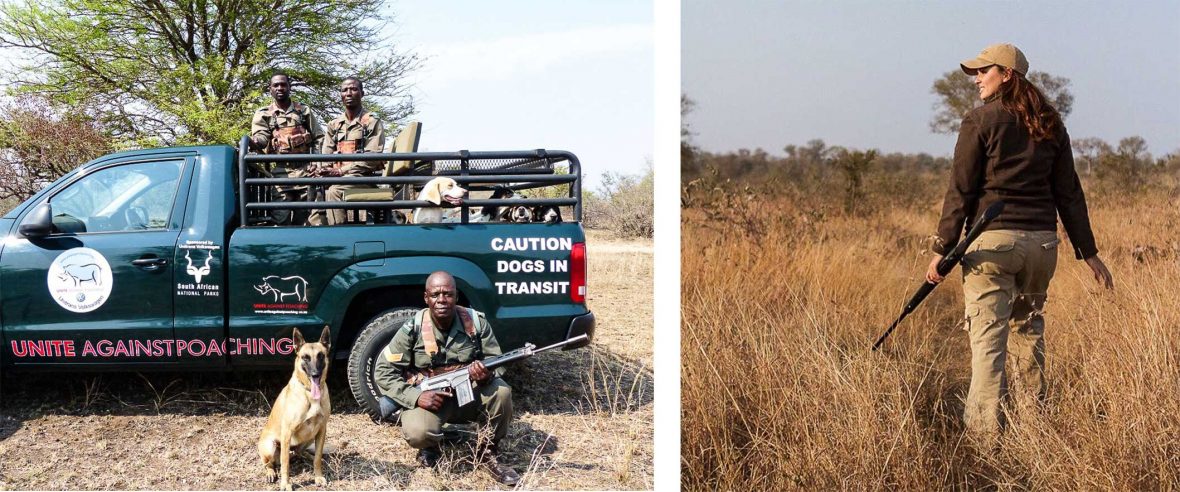

Having witnessed rhino poaching for over seven years, Lee-Anne decided to take action in 2012 by educating guests, local communities and school children about the unnecessary slaughter going on throughout South Africa. Since then, she’s received enough donations to operate two planes plus 30 dogs to support the K9s, Kruger’s canine crack-poaching team, which made 87 arrests last year.

Although the outlook is bleak, there are pockets of hope, and Lee-Anne’s words spurred me on to track them down. Phinda Private Game Reserve, which is owned by safari operator andBeyond, has lost only three rhinos in the last eight years, despite being in one of the country’s top poaching hotspots. By contrast, a nearby reserve has lost almost all of its rhinos.

Much of Phinda’s success is down to Simon Naylor, a legendary reserve manager whose Instagram account is the stuff of conservationist dreams. His kind but no-nonsense manner is as trustworthy as it gets, and after a 30-minute chat, I’m in awe. “For the last few years the rhino growth rate for both black and white has been negative—in other words, more animals are dying than are being born,” he says. “Never in the history of the species has the decline been more rapid—the species now faces extinction. The effort to reverse this requires urgent action.”

“We’ve now moved 87 of the 100 rhinos, and it’s been no small feat,” Simon continues. “Fifteen were flown, 12 were heli-slinged, and 32 were moved by road. Eight in total have been taken from Phinda. When moving these animals, you’re dealing with tight margins of time. We’ve had to work with changing weather patterns, mounds of paperwork and sweltering temperatures. Thankfully, all 87 rhinos have been delivered safely.”

This is a man who’s used to applying bit of elbow grease when it comes to these 1.5-tonne animals. Once sedated and blindfolded, each rhino needs to be moved into a transportation crate; the easiest way is to get it to walk of their own accord, but when that’s not possible, an army of helpers are needed to shift the weight. “The team effort makes it an incredibly emotional experience,” says Simon.

It’s not just the necessary muscle that makes people a central part of Phinda’s conservation success story; Simon’s tireless work engaging with Phinda’s surrounding five communities is all in the name of conservation. “The biggest threat to rhinos is often close by,” he explains. “Local people must feel and see the benefits of protecting rhinos, so they’re not persuaded to join illegal criminal syndicates to poach and trade in rhino horn.”

RELATED: How to travel and make the world a better place

That means providing jobs, sharing the tourism economy and building infrastructure, but as Simon explains, “it also means being present at every community meeting and proving a genuine commitment. Doing this over the course of 27 years has led to robust relations.”

In 2016, andBeyond made the difficult decision to de-horn its rhinos at Phinda to reduce the threat of poaching. This was partly in response to surrounding landowners doing the same, and not wanting to be, as Lee-Anne calls it, ‘sitting ducks’.

Karkloof has benefitted from an influx of cash and experience. The new owner of Karkloof Safari Villas, software tech entrepreneur Colleen Glaeser, has brought her own security experience to the reserve—Axxonsoft technology uses artificial intelligence to differentiate between humans and animals to target poachers. The solution is cheaper and more accurate than drone and thermal technology solutions and currently helps to secure over 2,000 acres of land in South Africa.

While this works in the short-term, Chris has also worked with reserves throughout South Africa to implement longer-term solutions, and has a bigger-picture idea of where rhino conservation needs to be, how they might get there, and the issues that might stand in their way. “Too often, there’s a disconnect between what tourists, communities, landowners and conservationists want,” he says. “We have to listen to each other and work towards feasible solutions. We have to make these places work, and we have to keep protecting land for conservation.”

His words ring true for issues world-over. If I’ve learnt one thing, it’s that there’s no quick fix when it comes to saving rhinos.

—-