For eight years, I have studied digital nomadism, the millennial trend for working remotely from anywhere around the world. I am often asked if it is driving gentrification.

Before COVID-19 upended the way we work, I would usually tell journalists that the numbers were too small for a definitive answer. Most digital nomads were traveling and working illegally on tourist visas. It was a niche phenomenon.

Three years into the pandemic, however, I am no longer sure. The most recent estimates put the number of digital nomads from the US alone, at 16.9 million, a staggering increase of 131 percent from the pre-pandemic year of 2019.

The same survey also suggests that up to 72 million “armchair nomads”—again, only in the US—are considering becoming nomadic. This COVID-induced rise in remote working is a global phenomenon, which means figures for digital nomads beyond the US may be similarly high.

My research confirms that the cheaper living costs this trend has brought to those able to capitalize on it can come with a downside for others. Through interviews and ethnographic fieldwork, I have found that the rise of professional short-term-let (short-term rental) landlords, in particular, is helping to price local people out of their homes.

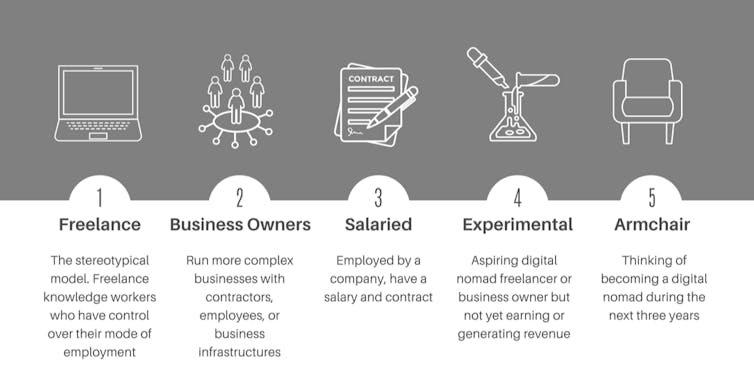

Before the pandemic, digital nomads were mostly freelancers. My research has identified four further categories: Digital nomad business owners; experimental digital nomads; armchair digital nomads; and, the fastest emerging category, salaried digital nomads.