Iran. Those who visit tend to love it, but for many, it’s become synonymous with travel bans, cultural restrictions, poor human rights and high security. But what’s it like to travel there? Here’s what featured contributor Leon McCarron says.

In late winter of 2014, my friend Tom Allen and I flew from London to the Iranian capital of Tehran, then traveled onwards to the ancient city of Esfahan by bus. Under one of the 33 arches of Si-o-se-pol—the largest and most beautiful of the major bridges across the Zayanderud river—we met our friend Saeid, who drove us high into the Zagros mountains.

He left us where the road ended, and we walked on, alongside a small trickle of water buttressed on both sides by deep snow. A few hours later, at around 3,500 meters, we stopped where the water too halted; or perhaps more accurately, where it began.

It’s this spring that gave birth to the Karun, the longest river in Iran and the natural highway that Tom and I would follow for five weeks, on foot and by kayak, until we reached the Persian Gulf. And so, we began the journey south, into a blizzard and, for me, very much into the unknown.

After many years of international sanctions, which have squeezed the Iranian economy almost to breaking point, there was something of a rapprochement under the recent presidency of Hassan Rouhani. This resulted in the much-feted “Nuclear Deal’ of 2015/16, in which Iran agreed to reign in nuclear activity in return for an easing of economic sanctions.

Any progress on that front, however, was rolled back in summer 2018 when President Trump, after months of rhetoric, eventually pulled out of the Obama-era agreement. Coupled with Trump’s much criticized ‘travel ban,’ which has also been labeled a ‘Muslim ban’ for the fact that it primarily targets Muslim-majority countries, we’re back to a situation where diplomatic relations are as strained as ever.

And as a result of the new sanctions imposed by the US on Iran, British Airways and a host of other European carriers put a halt on their direct flights to Tehran. The movement of people to and from the west is as tricky now as ever.

For non-British Europeans, it’s still relatively easy to get visas, and to travel via indirect flights through Istanbul or Kiev or elsewhere. If we do visit, we can expect things on the ground to remain much the same as before.

It’s almost a cliché by now, but Iranians are perhaps the friendliest people in the world, and just about anyone that has been will testify enthusiastically to this. One does have to be respectful, as always in such a conservative Islamic society. Women should cover their head and wear loose clothing, and men should avoid shorts. Alcohol is out of the question, and conversations about religion generally best avoided with strangers.

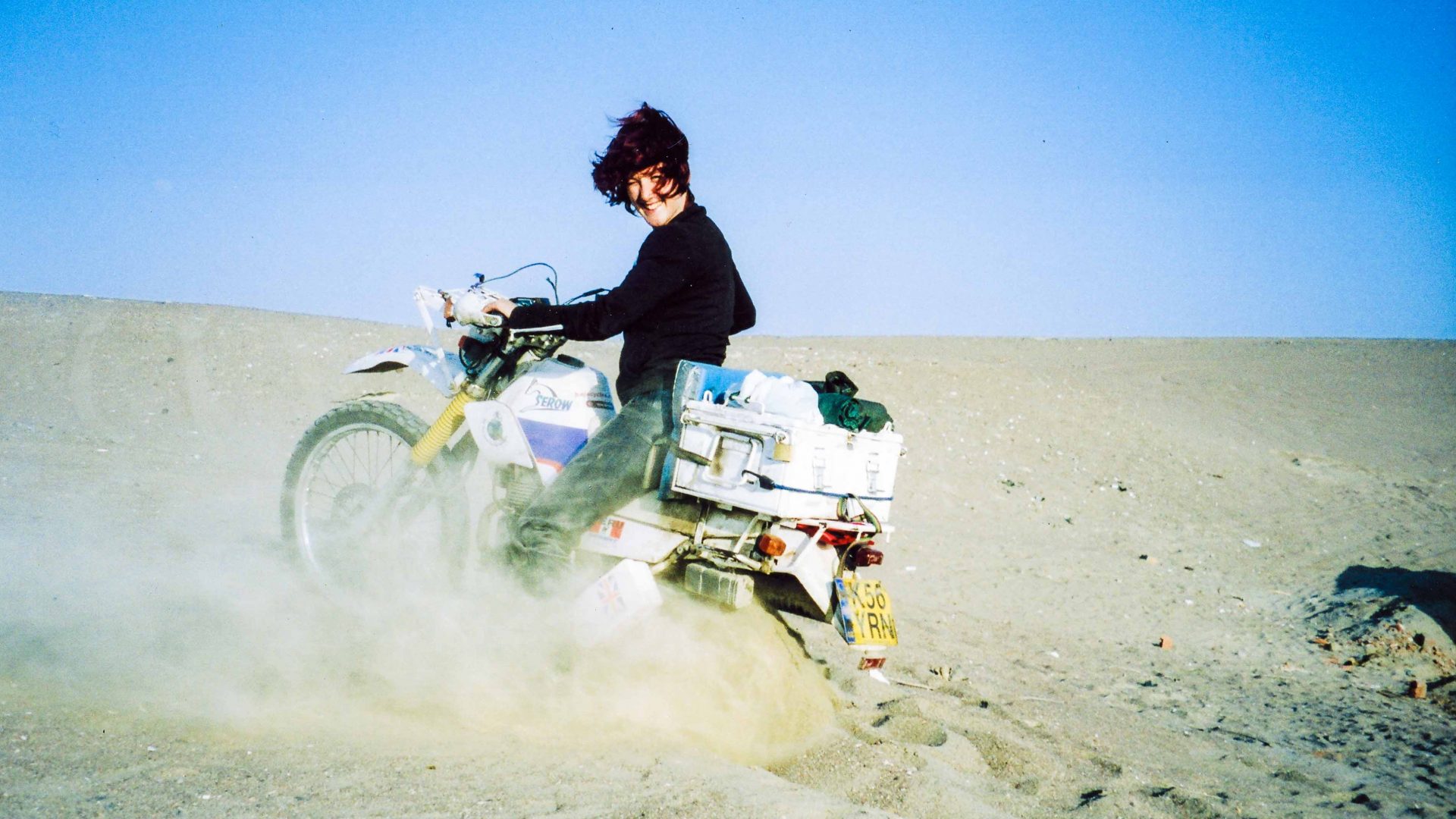

RELATED: The woman who motorcycled solo around Iran

There are police—and secret police—everywhere, but if you’re following the rules and simply touring around, you’ll have no issues. Iran is not a dangerous place as such—rates of petty crime are extremely low, and the risk of a terrorist attack is much less than in major European cities like Paris and London.

And let’s not forget this is truly a remarkable country; inimitably rich in history and natural beauty, and home to some of the oldest civilizations on earth. All those places that you’ve heard about—Persepolis and Shiraz, the mosques of Esfahan, the Silk Road, the desert city of Yazd, the ski slopes of the Alborz and the otherworldiness of Qeshm island—they’re absolutely worth the hype.

Had I listened to the advice of the UK Foreign Office, I would never have gone to follow the river Karun. I’ve written elsewhere about the inherent importance of these government bodies (FCO, State Department and equivalents), but they also deal in generalizations, and nuances get lost. The challenges posed by a visit to Iran now, even for Americans and Brits, is still more logistical than anything else.

The best memories of my travels in Iran are from the time spent with Iranians, on the streets and in their homes. The film that Tom and I made was designed as our offering to the canon of alternative narratives from the country; adding much-needed humanity to a much-demonized country. Four years later, and in the current global climate, such storytelling seems even more important. If you look beyond the politics, deep into the heart of Iran, you find a very special place indeed.