Far from the pre-packaged, plastic Vodou pushed to tourists en masse, Paul Clammer heads to Haiti in search of the real spiritual deal.

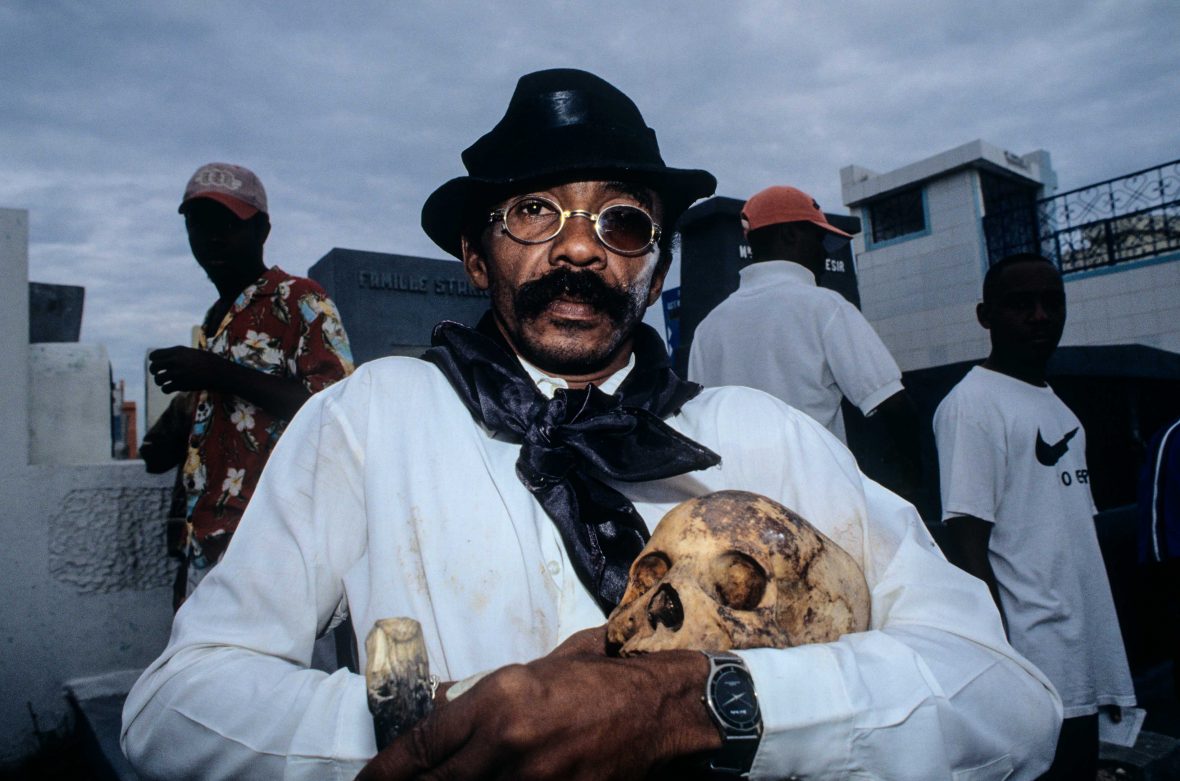

For as long as travelers have visited Haiti, they have been intrigued by Vodou. During the country’s tourism boom of the 1970s’, nightclub floor shows relied heavily on jungle drums and black magic, and chalk-faced witch doctors would appear from a puff of smoke to front advertising campaigns for the national tourist board.

A taste of this pre-packaged exotica still lingers today at Labadee, a private beach resort run by Royal Caribbean on Haiti’s north coast. Dancers still writhe to hypnotic rhythms in a floorshow, breathing fire and walking on glass, hoping to lure tourists away from the all-you-can-eat buffet. It’s fun, but as far from a lived religion as it’s possible to get. To experience that, you have to head far from the crowds and into the country.

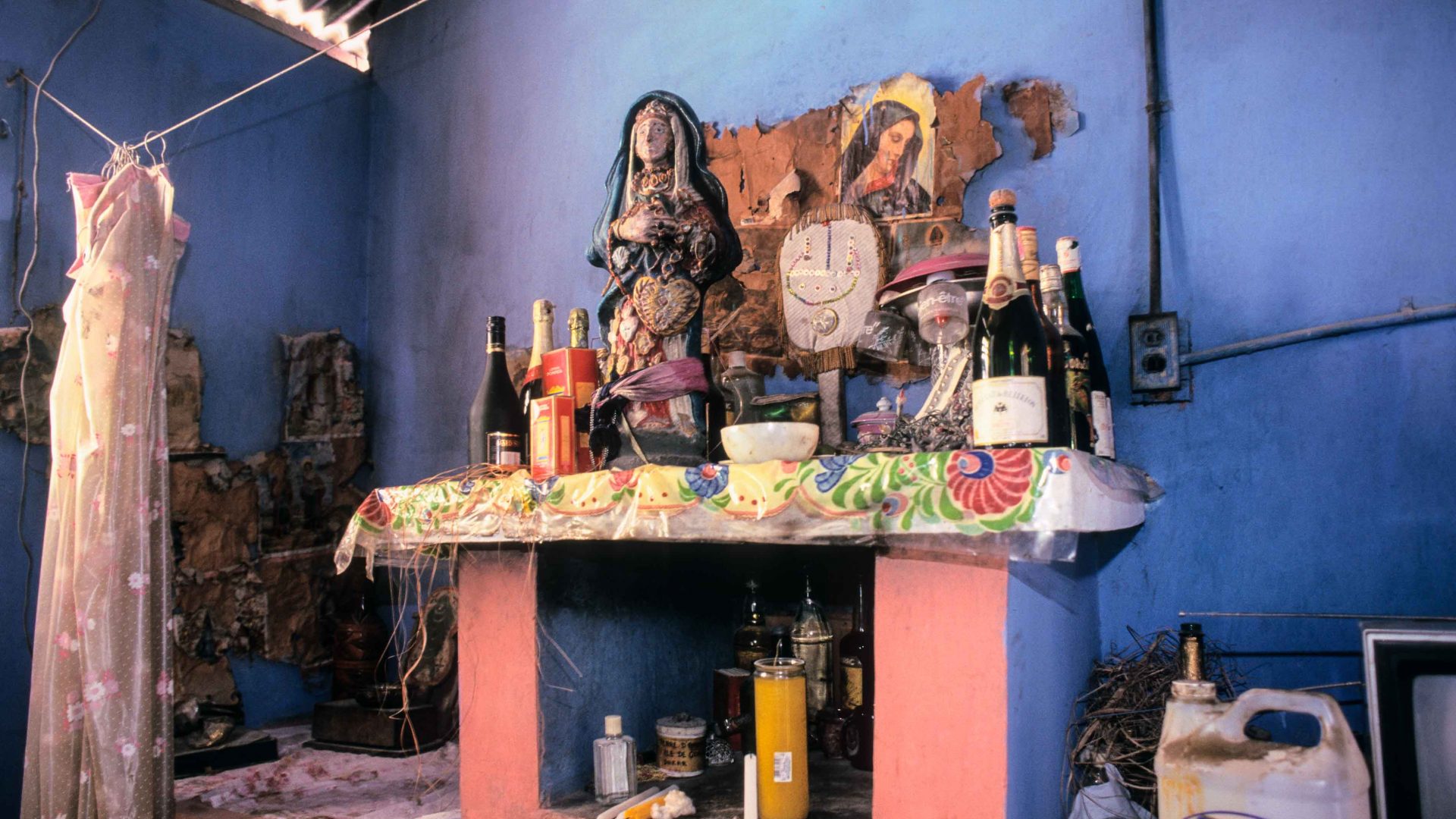

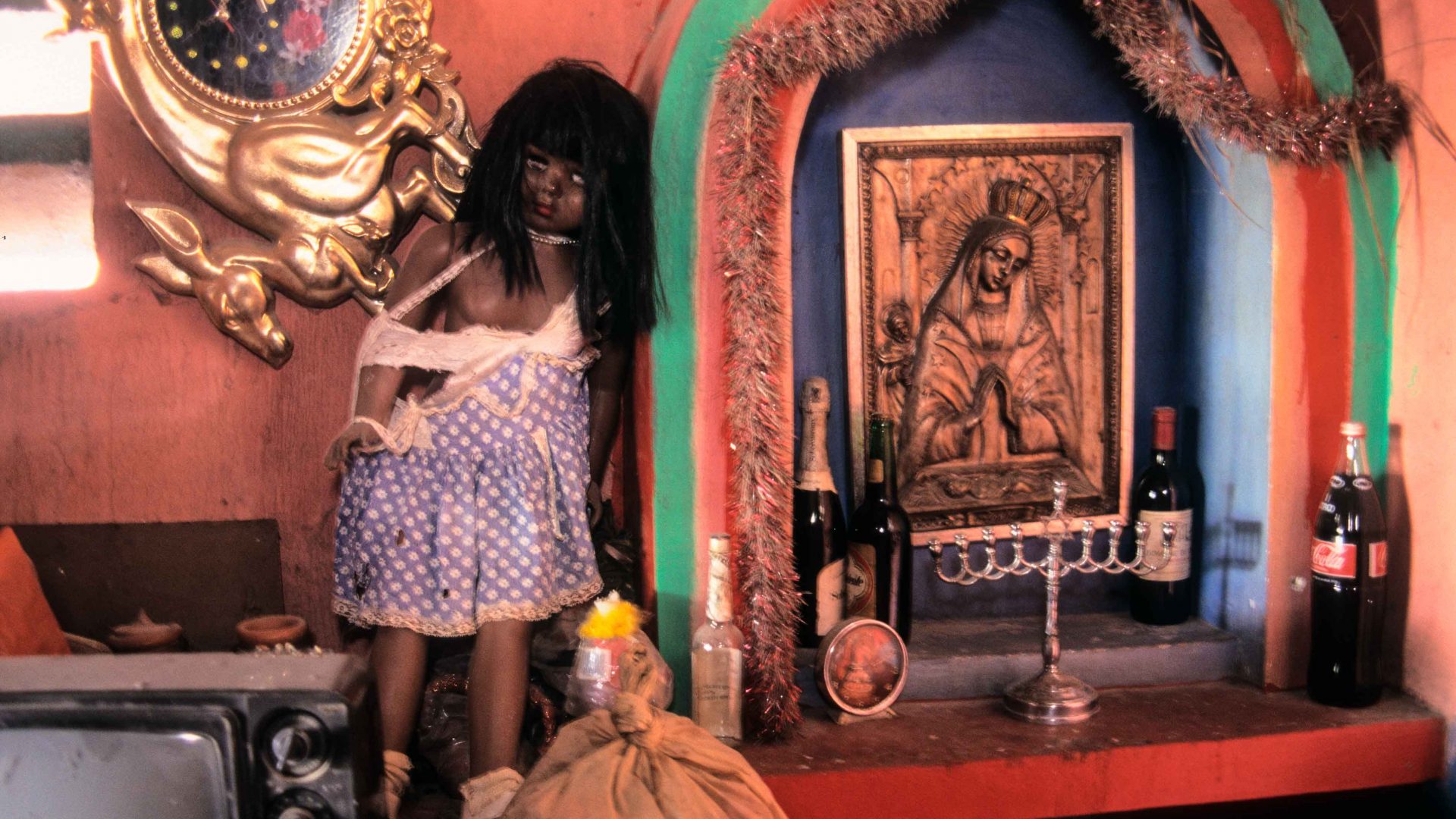

Vodou (the anglicized spelling ‘Voodoo’ is considered pejorative) is not a religion of great cathedrals. Temples tend to be small affairs, tucked away from immediate view, frequently rendering the religion invisible to the casual observer. A first-time visitor to Haiti may have heard the old adage that the country is 90 per cent Catholic, 10 per cent Protestant, and 100 per cent Vodou—no wonder they remain baffled. Churches seem to be everywhere in Haiti—so where is the Vodou?

On my first visit to Haiti, I was let in on the secret. Picture Vodou like a power grid, I was told. It’s everywhere, covering the entire country; you just need to know how to plug in.

RELATED: Adventures with impact for 2018

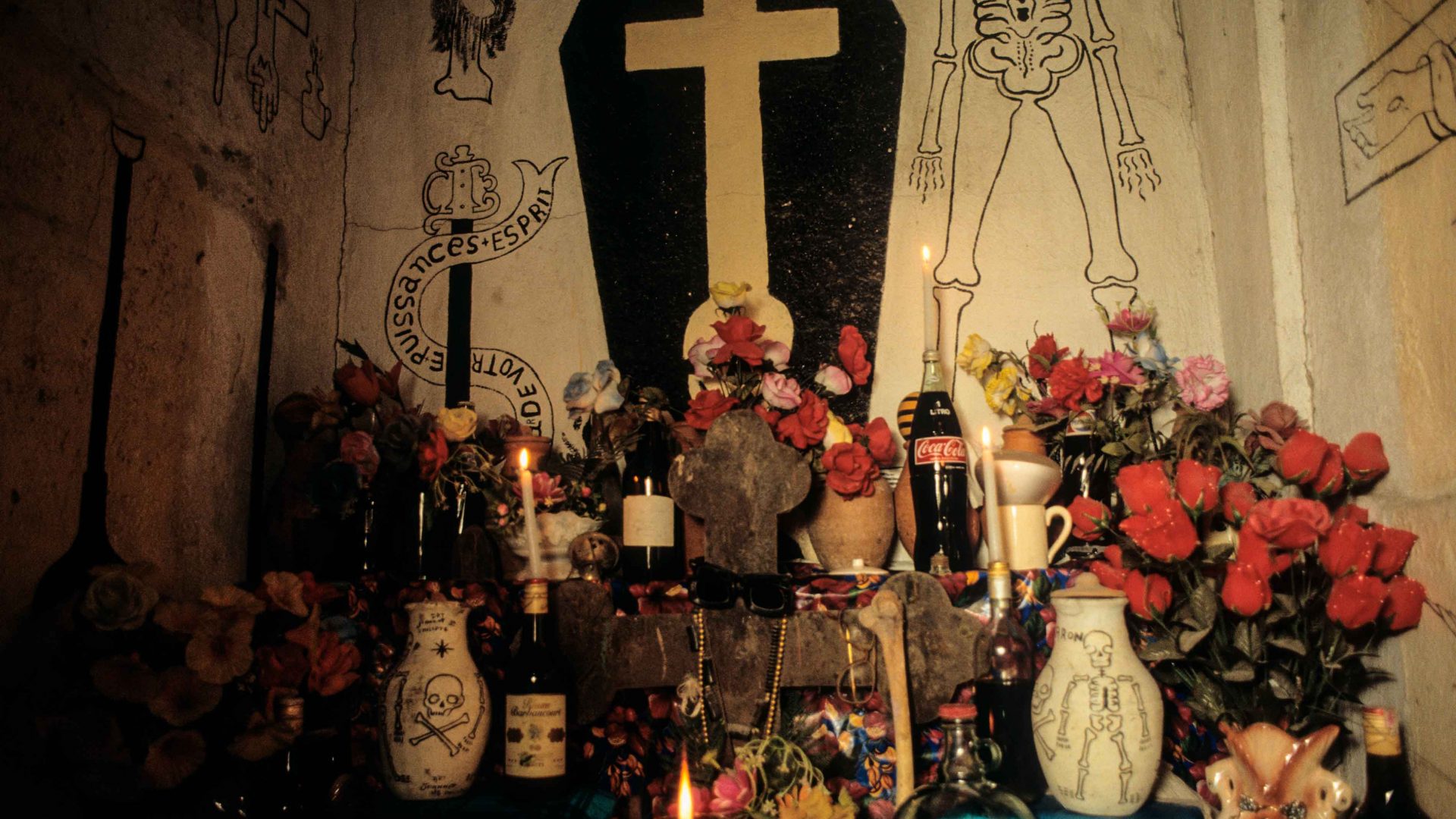

Cemeteries are a good place to start. Here, even at the graves of Christian believers, you find evidence of the lwa, the Vodou spirits. A crucifix may be marked with black and purple, with burnt candles at its base, and discarded bottles of rum represent the offerings made to Baron Samedi, the lwa who guards the passage from the this world to the next, and his wife Brigitte. It’s also common for the recently deceased to have food left out for them to help their spirits back across the sea to ancestral Africa.

A few days after seeing the caves, I was taken to another place that claimed to be the site of the Bois Caïman ritual; later still, I heard of at least two more. One was past the ruins of Breda, the plantation where revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture was born. After the tracks gave out, past the fields of sugarcane, we approached the stump of a mango tree where my guide told me Legba would judge if my intentions were pure enough to visit the sacred spot.

RELATED: How to travel like a travel writer

Drawing level, a white butterfly appeared from nowhere and landed on my shoulder. After 10 seconds of contemplation, it flew off. The judging of the lwa complete—I was assured we could now continue. Another mapou tree marked the spot, but there was no way to tell if this was the ‘real’ Bois Caïman either. Perhaps, as the revolution burned across northern Haiti, the slaves felt that Bois Caïman was everywhere.

Africa continued to water Vodou roots even after the revolution. Near Gonaïves is the sacred pilgrimage site of Souvenance which, according to oral tradition, was founded after the freeing of prisoners from a captured slave ship on the nearby coast, soon after Haitian independence.

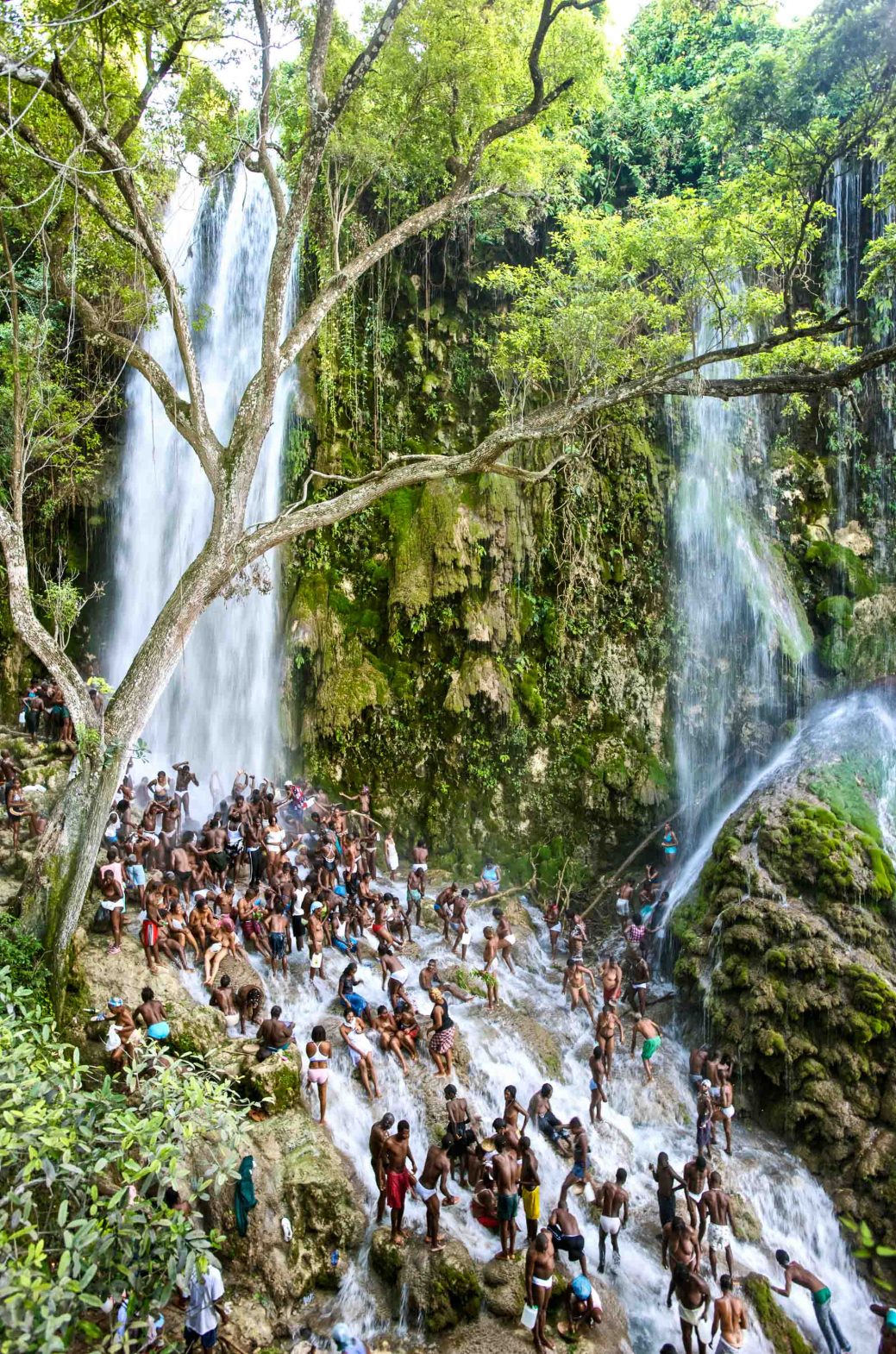

In other locations, Vodou still sits behind its Catholic veneer, such as the waterfall of Saut d’Eau; every July, pilgrims visit the spot where a vision of the Virgin Mary once appeared, matched in numbers by those taking the waters to offer prayers to Ezili Danto, the main lwa or senior spirit of one of the Vodou families.

Away from these major sites, the evidence of Vodou can seem hard to spot in Haiti. But look carefully, and the signs are everywhere—the charms in the trees, the candles burning in unexpected places, and the saints and veve painted on walls. You just need to plug in.