If you want extraordinary Mayan sites without the crowds, you just have to head deep into the jungles of the Yucatán Peninsula, discovers Graeme Green.

The road ahead is blocked. Standing between us and the ancient Mayan city of Calakmul, deep in the Yucatán Peninsula, there’s a strange and colorful bird with either a perverse sense of humor or a stubborn streak. Every time we stop the car, the bird—a wild, blue-headed Ocellated Turkey with wings of green, brown and gold—moves to the side of the road. But as soon as we rev the engine or inch forward, it moves right back in front of us, making it impossible to pass.

There are worse ways to be held up; the bird’s immovability allows us ample time to get out and photograph it. But after 10 minutes, it stretches the patience. We finally make it past, only for another technicolor turkey to appear, shortly joined by a posse of feathered friends further along. This could take some time…

Wild turkeys aren’t the only obstacle to reaching Calakmul, one of the most important and powerful cities of the Mayan empire. There’s also the distance (it’s 373 miles/600 kilometers from Cancún) and the time it takes to drive deep into the Yucatán to reach this archaeological hotspot, 22 miles (35 kilometers) from the Guatemala border. It also means Calakmul and other intriguing sites, including Dzibanche and Chicanná, receive a miniscule fraction of the almost-2.5 million visitors who fill the grounds of Chichén Itzá each year, and other easy-to-access sites such as Tulum and Coba.

RELATED: How did Tijuana become Mexico’s go-to foodie city?

The other hurdle is the fact that so few people have heard of these remote sites. Those who have, however, know that Calakmul is one of the most interesting archaeological areas in the entire Yucatán Peninsula. And that’s certainly enough to justify a road trip.

From Cancún airport, we drive past the laidback beach town of Tulum, detouring to the cenotes (natural pools in collapsed caves) common in this region of Quintana Roo. The coastal road then opens up, traffic thins and a sense of adventure sets in. Reaching the sleepy seafront town of Mahahual and, further still, Bacalar, the ‘Lake of Seven Colors’—a massive expanse of water striped from white to deep, dark blue—there are notably fewer tourists and a feeling we’re reaching places few others do.

A long highway drive takes us across Quintana Roo, into the Campeche region, and onto Xpujil, the nearest town to Calakmul and home to more significant Mayan sites in the surrounding countryside. We visit Chicanná in the morning, accompanied by birdsong—but no other visitors. “The Maya were never helped by extra-terrestrials,” reads a sign by the entrance, sounding a little tired of answering the question.

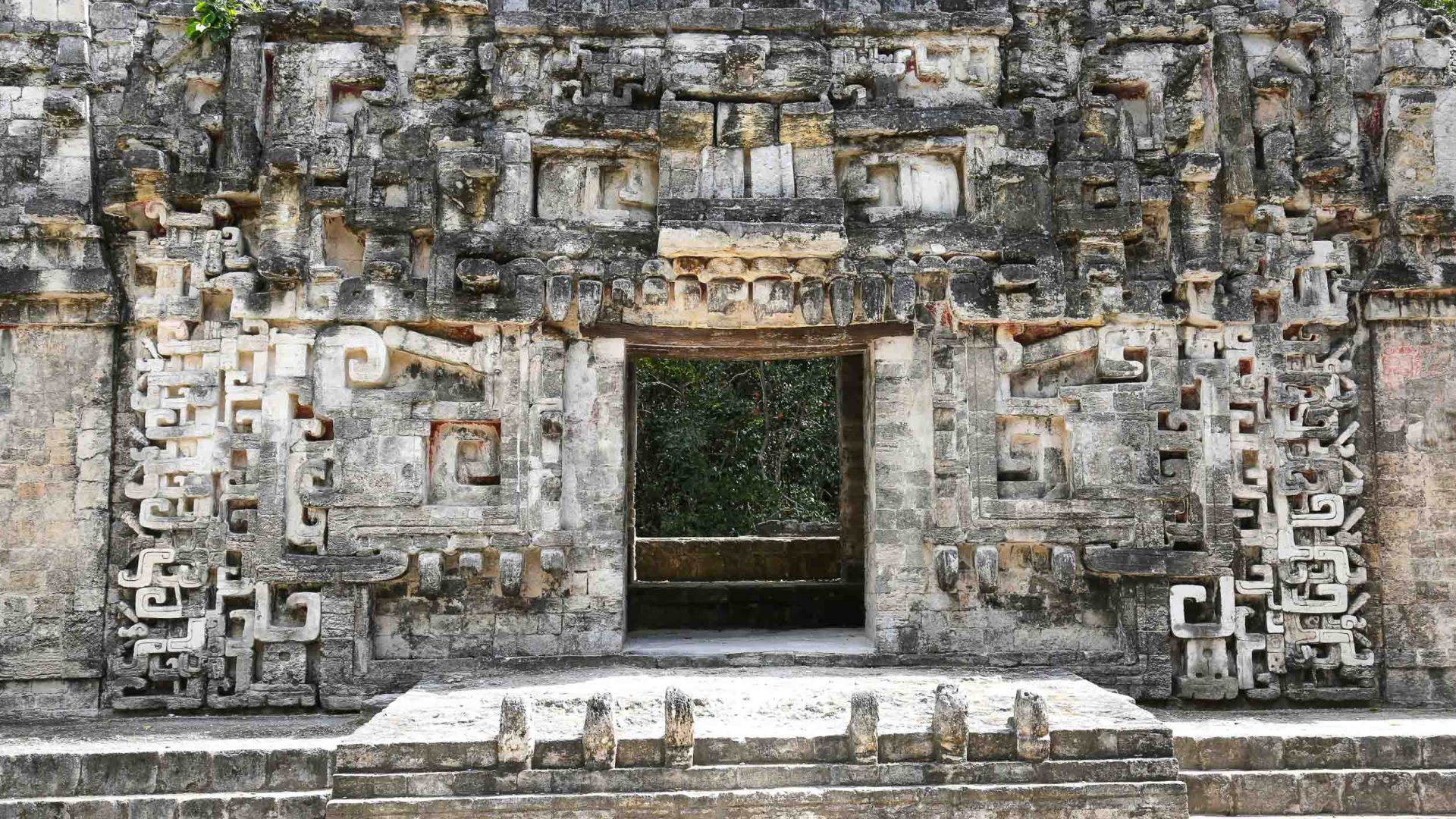

The structures inside are more elaborately decorated than those in Quintana Roo, a common feature in the Mayan structures of Campeche. On the ornate façade of Structure 20, an ancient house, are numerous carvings including masks of Chaac, a human-reptile god of water and rain. Stone steps lead up through an arched doorway into empty stone chambers; the holes in the walls most likely housed statues of deities. Deeper into the site, we reach the House of the Mouth of the Serpent, the arched doorway representing a mouth, with six large teeth on the step below.

After a second night in Xpujil, we leave early for Calakmul (mornings offer the best chance of seeing wildlife in the biosphere reserve surrounding the ruins). Driving slowly down a pot-holed road, we spot an osprey eagle watching from branches high above. Below, a capybara (native South American rodent) springs from the forest and runs across us the road, narrowly avoiding a collision.

RELATED: The Caribbean as it used to be: How Montserrat is coming alive again

From 250AD onwards, Calakmul was one of the most important Mayan cities. Archaeologists believe it was home to around 50,000 people in the seventh century and the heart of what was the ‘Kingdom of the Snake’, and a powerful rival against Tikal across the border in Guatemala.

Its name, which means ‘City of the Two Adjacent Pyramids’, comes from several Mayan words pieced together by the biologist Cyrus L. Lundell who helped rediscover the site in 1931. The massive pyramids are just two of around 6750 identified structures that stretch across the sprawling 27 square kilometers of the archaeological zone, though we just explore the smaller central core.

Plenty of other wildlife lives here too, including Howler monkeys, vultures, jaguars and pumas. Geremias Diaz Trejo, one of the men working to clear overgrown paths, says he sees a jaguar or other big beasts almost every day here. “This is one of the most beautiful places because you have the archaeology and the wildlife and the nature. Chichén Itzá doesn’t,” he says. “If you just take a seat somewhere quiet, you might get lucky and see something.”

Later, we climb the underwhelmingly named Structure 2. At 45-meters-tall, it’s one of the tallest pyramids built by the Mayans. Joined by a small cluster of fellow visitors, we spend a while at the top, enjoying the feeling of standing among these mighty ruins, deep in the jungle. Howler monkeys disturb the otherwise silent scene, their grunts and roars carrying on the wind. It’s moments like this that are the reward for travelers ready to make a long drive—and who can make it past the turkeys.

—-