Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

Not only did he shape how the world saw Japan through his landscapes, the works by 19th-century artist Katsushika Hokusai continue to inspire today. Shafik Meghji goes on the trail of Japan’s greatest artist.

A few hours after arriving in Japan, jetlagged and slightly disheveled, I climbed a steep flight of steps to the candy-striped Chureito Pagoda in Yamanashi Prefecture for my first glimpse of Mount Fuji.

Despite the distractions of a “Please beware, there is a bear in the area” sign and a gaggle of tourists brandishing selfie sticks, tripods and plastic cherry blossom sprigs to pose beside—the real stuff was not due for a fortnight—the snow-topped volcanic peak was mesmerizing. Although I’d never seen it before, it was immediately familiar.

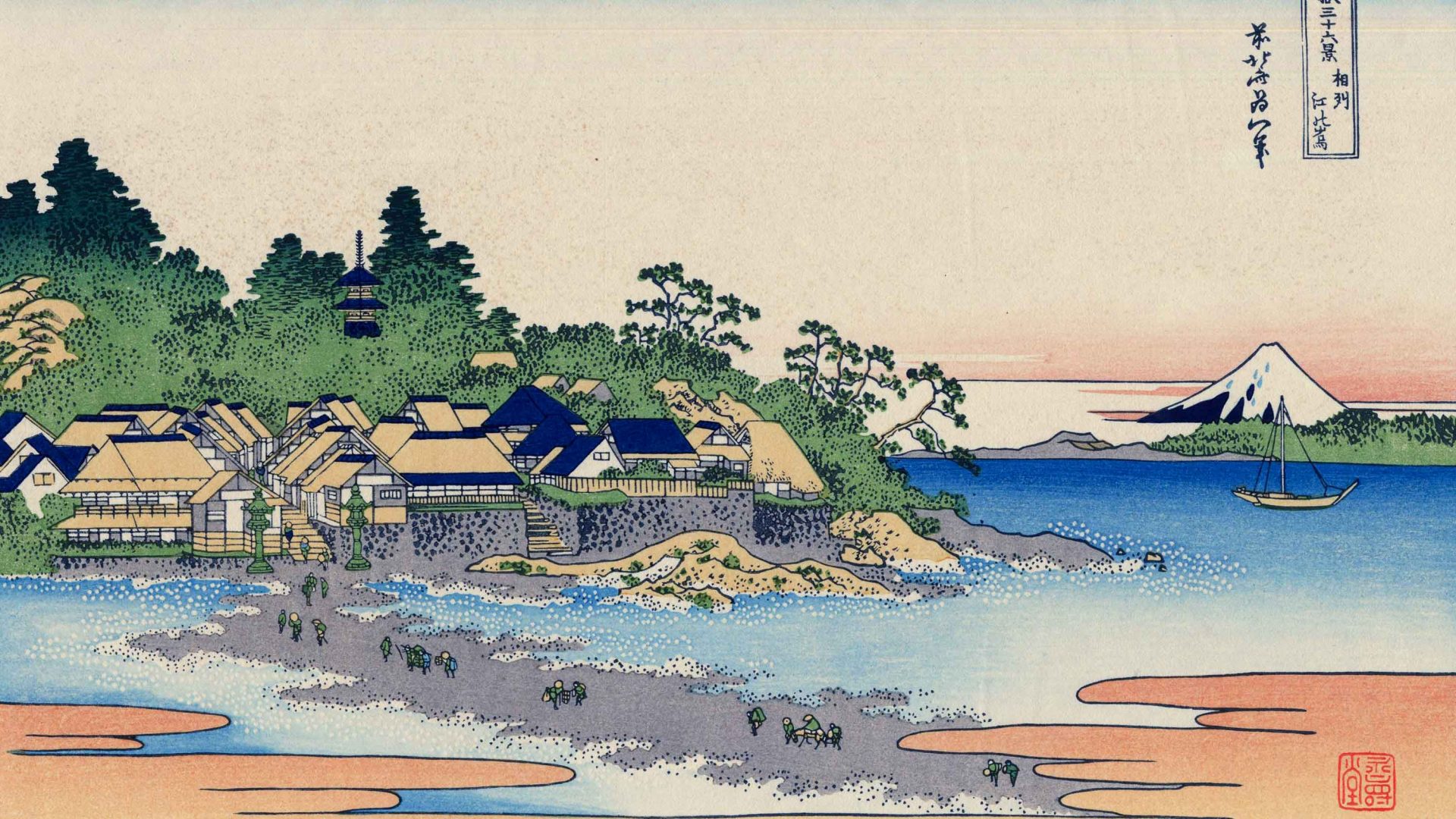

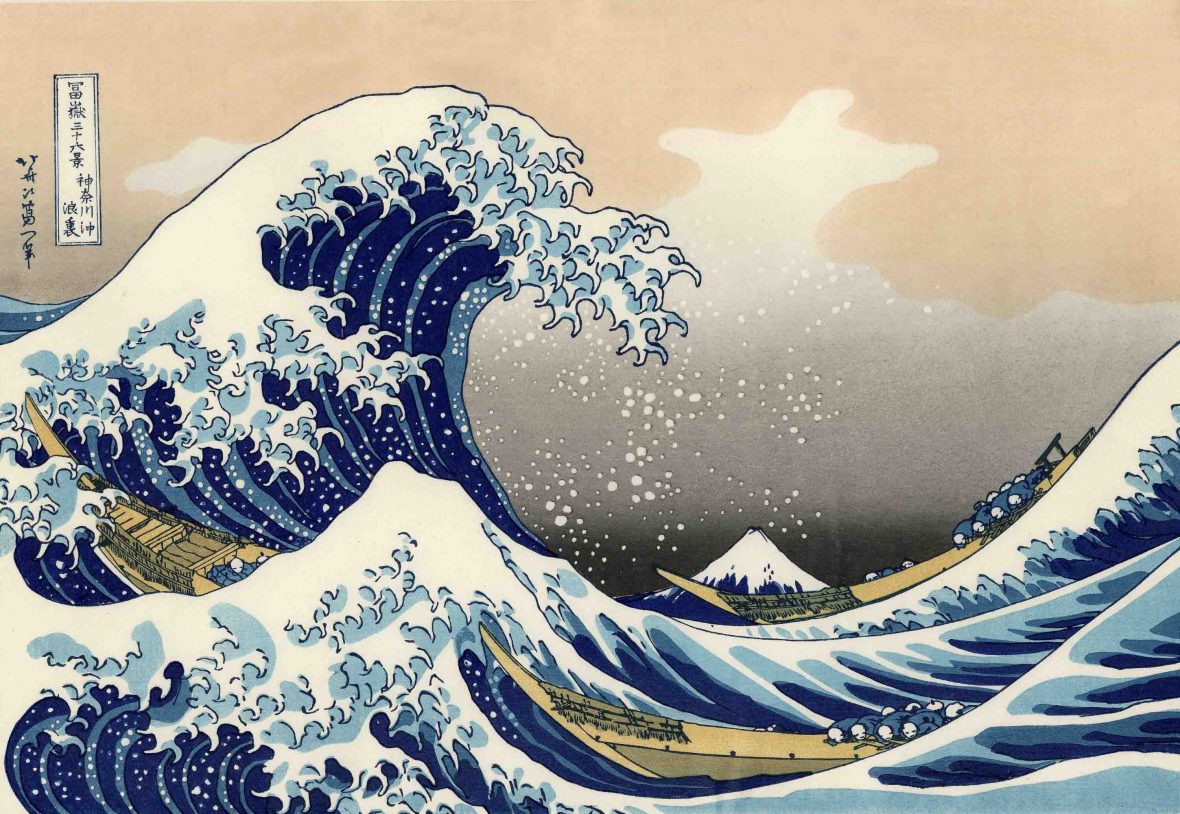

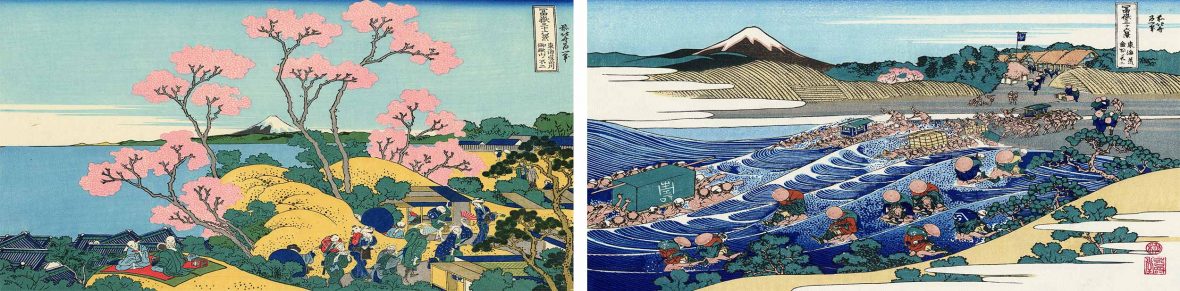

Like travelers for almost two centuries, the picture of Japan in my head was thanks to Katsushika Hokusai, perhaps the country’s greatest artist. Even if you don’t know the name, you probably know the work. His series of Ukiyo-e—color woodblock prints—Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji, produced between 1830 and 1832, show the peak from different angles, at different times of the year, and in different contexts, both realistic and fantastical.

In total, he is estimated to have made some 30,000 pieces of art, an astonishing figure given the hardships he faced. He suffered severe poverty, was struck by lightning at the age of 50, and had a stroke in his 60s. His first wife, second wife and eldest son all died before him, he was lumbered with his grandson’s huge gambling debts, and lost much of his work in a fire at his studio.

It’s perhaps not surprising that he was prone to superstition: every morning he drew a picture of a Chinese lion and then threw it away in an attempt to ward off evil.

RELATED: Snow food: Japan’s unusual Alpine cuisine

According to Hokusai, he only started making art that was “worth taking into account” at an age when most people are contemplating retirement. He produced Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji when he was in his 70s, and a decade later, traveled from Edo, now Tokyo, to live in the tranquil town of Obuse, 134 miles (215 kilometers) northwest. This move heralded a remarkable burst of creativity.

The highlights though are two lavishly decorated floats, carved and painted by Hokusai himself. Remarkably, they were used in local festivals until only 40 years ago, when it was decided they’d be preserved for posterity.

While Obuse was his eventual inspiration, Hokusai, who was born in 1760, spent most of his life in the Sumida district of Edo (now Tokyo). Since 2016, the area—whose landmarks feature in many of his early works—has been home to a striking museum dedicated to his art.

RELATED: Inside Tokyo’s capsule hotels

Hokusai started drawing at the age of five, became a wood-carving apprentice at 14, and entered the studio of a Ukiyo-e master at 18. Over the course of a peripatetic life, he moved house 93 times and adopted over 30 different artistic names, including the ‘Old Man Crazy to Paint’. Although most associated with woodblock prints, Hokusai also produced sketches, paintings, illustrations, murals, picture books and even erotica.

Later, I stroll over to the eastern edge of Obuse, to the 190-year-old Ganshoin Temple. Few foreign tourists make it here, but those who do are rewarded by one of Hokusai’s greatest works. In the gloomy interior, a ceiling mural of an unfurling phoenix appears luminously bright. The bird has a knowing, almost mischievous expression, its beady eye seemingly following you around the room.

“The phoenix is a symbol of eternal life,” my guide Ayako Furuya explains, “and Hokusai himself believed he would become divine if he lived to 100. He was very health-conscious and exercised every day.”

Sadly, Hokusai only made it to 89. His last words were reputedly: “If heaven will afford me five more years of life, then I’ll manage to become a true artist.”

Back home in London, I still have Hokusai’s images of Japan in my head: Giant crashing waves, Mount Fuji covered in snow, endlessly spiraling phoenixes. But, after seeing first-hand the landscapes that inspired him, those images are now even clearer.