The daily sailings of the Calmac ferry around Muck, Eigg, Rum and Canna in Scotland’s Inner Hebrides amount to one of the best-value cruises in the northern hemisphere. Andrew Eames goes exploring—for $20.

It isn’t the usual cruise ship crowd. There are walking parties with dogs. Council workers in overalls. Twitchers—bird spotters—with tripods and chunky zoom lenses. A couple of gamekeepers, looking slightly out of place in their heavy waterproofs. And a bus party of tourists from Scotland’s east coast. All getting on the same boat.

No, I say to myself, it isn’t the usual cruise ship crowd, but then nor would you find the port of Mallaig, on Scotland’s west coast, on a map of cruise ship terminals. On one side of the quay are colorful trawlers and scallop dredgers filling their holds with ice, ready to put to sea, while over at the back, I can see the rail terminus of the West Highland Line, where the steam-hauled Jacobite, which has played the part of the Hogwarts Express in the Harry Potter movies, will be arriving.

More than 20 years ago when I last traveled out to Rum (which used to have a reputation as something of a forbidden place) it was in a mailboat that stood off in deeper water—so passengers intending to land had to clamber into a smaller flit boat to go ashore. Now, thanks to new terminals, Calmac’s MV Loch Nevis berths at as many as four islands in a day and can carry 14 cars—and by retracing its outward journey on the way back, makes a huge difference to communities living on the edge. It also means that visitors can do day trips to individual islands, or simply stay onboard all the way round, turning the whole thing into a mini cruise, for a day-trip fare of just £12.

RELATED: Snorkeling in Scotland? Taking the (cold) plunge

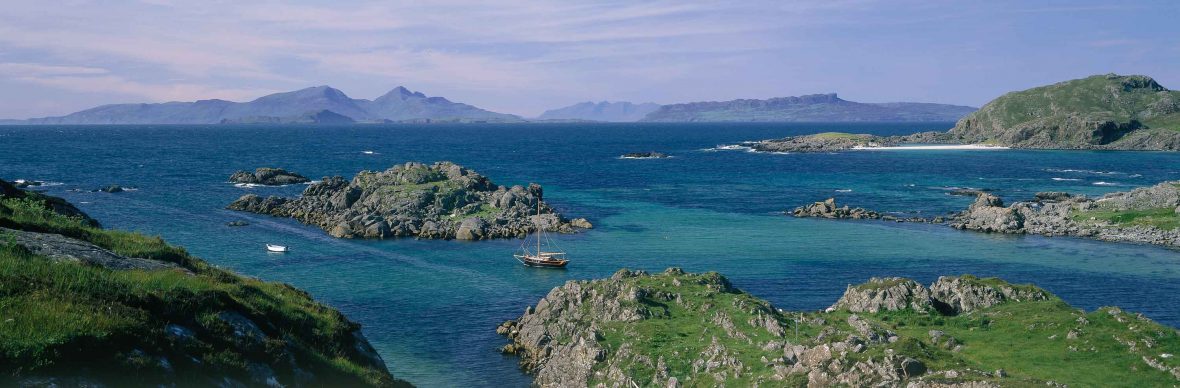

That morning we leave Mallaig at a civilized 10.15am, in immaculate conditions. The islands are basking in steep fingers of sunlight, the sea is millpond smooth, and there’s an air of subdued excitement. The twitchers are talking eagerly about the sea eagle project on Rum, which now has a fancy bunkhouse and no longer discourages visitors. The council workers are already tucking into a plate of chips in the on-board restaurant, and the bus party are bagging seats in the wind-sheltered parts of the deck.

After skirting Eigg’s seal-rich skerries (small, rocky islands) for another hour or so, the boat’s movement becomes more pronounced as we cross to Rum (population 20), broadsiding a gentle Atlantic swell. As we berth in the sheltered surroundings of Loch Scresort, I say farewell to the teacher and head ashore myself, along with the gamekeepers and the twitchers.

RELATED: ‘Britain’s toughest trail’: Is Scotland’s Cape Wrath Trail as hard as they say?

Back in the late 19th and early 20th century, this island was the plaything of a wealthy industrialist, George Bullough, who built a castellated hunting lodge here, kept alligators in the garden, and invited his friends for salacious house parties. More recently, its reputation for being off-limits to ordinary mortals was perpetuated by a major deer study, with only rangers allowed. These days, with a new bunkhouse and campsite, information office and shop, all that has changed.

The ferry is taking my new friend, the teacher, onward to Canna, but it will be back in two and a half hours to pick me up. That gives me more than enough time for a tour of Kinloch Castle, Bullough’s hunting lodge, led by Ross, an island resident with a strong Glaswegian accent and a fund of fabulous stories of the sort that you’d never get in a prim-and-proper country-house tour.

He shows us the under-the-stairs orchestrion—a mechanical orchestra—and the ballroom where the parties-with-prostitutes took place, and tells us how Bullough insisted all his castle builders wear kilts, despite the fact that the midges were terrible. Ross also reveals that Kinloch was only the second place in Scotland to have what he calls ‘tressie’, a word that has most of the group looking at each other perplexed, until someone whispers at the back: “Ah, electricity, of course!”