Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

In Brazil’s ‘other rainforest’, John Malathronas finds—among other things—one of the most biodiverse areas on the planet, potentially Brazil’s best beach, and black flies that cannot be killed.

“The first expedition to arrive here on 20th January 1602 was Amerigo Vespucci’s,” says Marcelo, our gregarious and knowledgeable driver, as we inch through the jungle in an open jeep.

Our party—two Brazilian families and me—nod knowingly. We are on the island of Ilhabela, Brazil’s fourth largest, and we’ve just left Vila, the main tourist hotspot, to traverse the rainforest to Castelhanos, one of Brazil’s most legendary beaches.

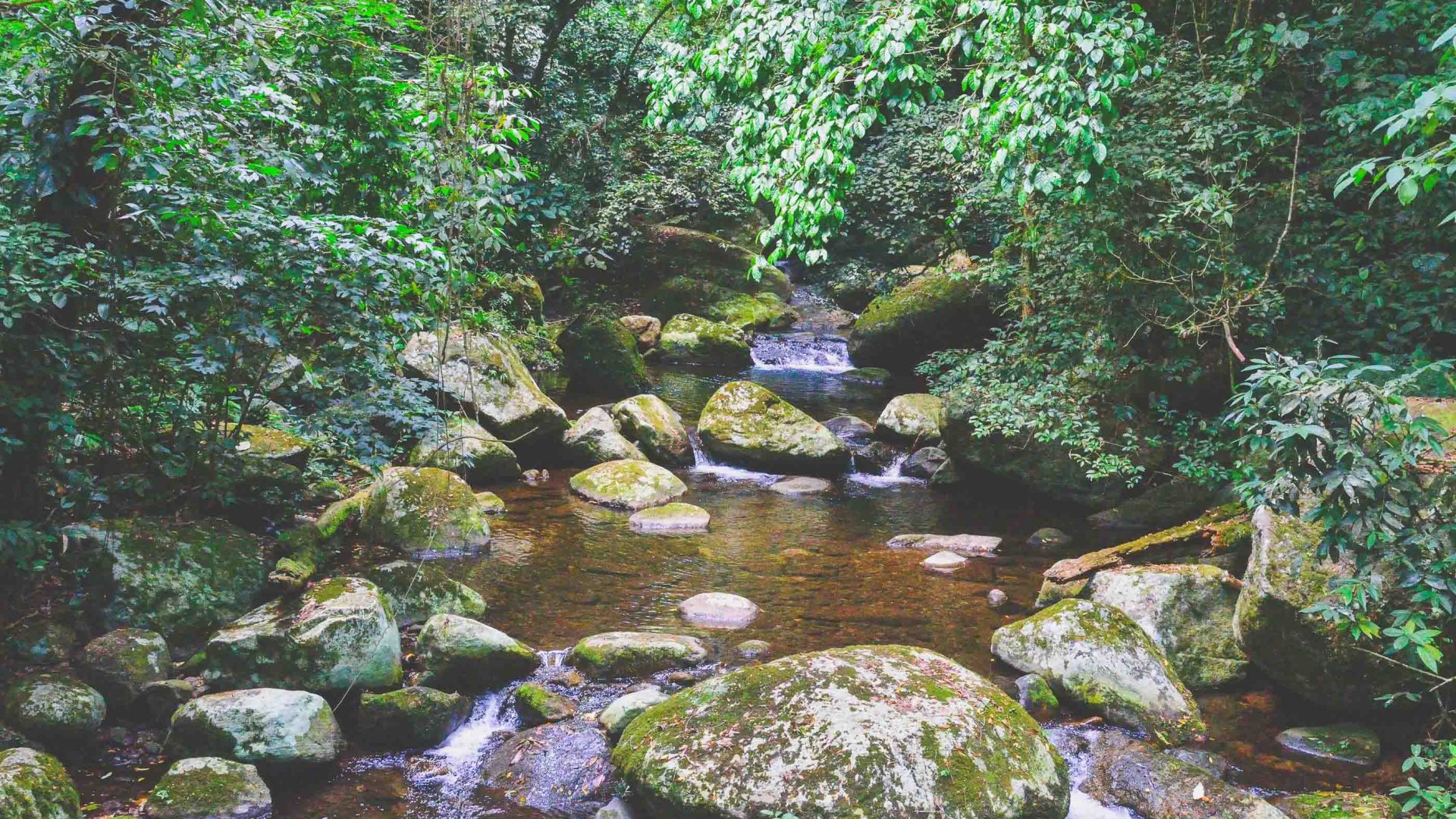

The narrow dirt road is puckered with stony ridges and sometimes water-clogged by the odd stream that’s capriciously decided to flow our way. Marcelo is navigating at crawling speed, avoiding potholes and sharp rocks with the same concentration a video gamer commits to dodging asteroids.

You see, there are two rainforests in Brazil. While the deforestation of the Amazon attracts attention, stokes up protests and dominates the news, its cousin, the Atlantic rainforest (Mata Atlântica), hardly registers a mention.

That’s because it’s already been annihilated; only about 10 per cent of the dense jungle that used to cover the Atlantic shore is left. The rest has fallen foul of the cultivation of sugarcane and coffee, as well as of encroaching urbanization, for Brazilians love their beaches and cling like seabirds to the coast.

RELATED: Where to find Cambodia’s best unspoiled beaches

Except that in Ilhabela, these roles are reversed: The island consists of 85 per cent virgin Atlantic Forest and only 15 per cent human settlement. It has the largest remains of Atlantic rainforest on the planet and has been declared a biosphere reserve by UNESCO. Maybe it’s because Ilhabela is separated from the mainland by a narrow channel, whose rip tides are notorious; it took the ferry 15 minutes to negotiate just three kilometers.

“Vespucci did well out of this trip,” Marcelo continues. “His description of the New World became such a bestseller that people started describing the whole continent as Amerigo’s.”

Marcelo describes various trees with gusto, probably to make up for the lack of animals. “That’s an ypé fighting it out with the lianas. That there with the reddish-brown berries is Araçarana spicewood.” At one point, he stops the car, runs to a tree and cuts off some leaves. “Smell,” he says.” They reek strongly of garlic. “Pau d’alho. Garlicwood. The leaves are used as an antiseptic.”

Towering trees are pressing in claustrophobically—no guesses as to why human eyes have evolved to see more shades of green than any other color. From the yellow tint of lime to the noble hues of malachite and jade, the green landscape is only broken by the bright red and orange of the odd orchid or bromelia.

RELATED: How to travel and make the world a better place

Then all of a sudden, the trees stop, and blazing sunshine dazzles our eyes. We’ve reached Castelhanos, a two-kilometer stretch of beach as stunning as anticipated: Oatmeal-brown sand fringed by the shamrock-green of the jungle facing an expanse of pelagic blue.

I notice that my travel mates are busy spraying themselves with repellent. “Borrachudos”, they shout, pointing at my legs. I look down and count six bites. “But I sprayed myself with DEET,” I complain. “No, take this” they insist, passing me a bottle of Citronella.

While Marcelo is speaking, the weather is turning. The welcome breeze that greeted us has turned stormy and the rippling waves have become surf-size breakers. We’re debating whether to start back early when we spot a local caiçara woman from a nearby barraca (beach taverna) walk towards us.

“Would you like to share some food?” she asks. We look at each other with surprise, but apparently she means it. She just got a message on the walkie-talkie that a party of Dutch arriving by boat was canceled because of rough seas and the barraca has already catered for 50. They’ll be paid, of course, but it would be a shame to throw all that food away.

We vote to stay.

After tucking into platters of seafood under the friendly scrutiny of the family toucan, I lose myself in the vastness of Castelhanos, hypnotized by the thundering crash of the waves. I’m glad there’s still some Atlantic rainforest left, so that we can experience its charms even for a passing few hours. I find myself struck by the same wondrous awe as Amerigo Vespucci, Hans Staden or Anthony Knivet centuries ago. It’s quite a feeling.

At least these unkillable black flies will ensure that such wilderness remains unsullied.