Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

In Greece, Holly Tuppen discovers an untouched playground where travelers are an essential drop in an ocean of biodiversity, mountain adventure, and centuries-old communities.

Moments of discovery have a way of creeping up when you’re least expecting them. Case in point: I’m in Greece, but I may as well be in the Andes, the Atlas Mountains, or the Himalayas.

The air is filled with tinkering cowbells, wafts of wood smoke,

soft chatter from the village square, and a cool breeze that’s whistled along

ice-cold rivers and echoic ravines to reach me. I never expected to find such wilderness

in a country I thought I knew so well.

Most people visit Greece for a dose of laidback island life, but I’m here for towering peaks and deserted trails. Since weaving west 300 kilometers from Thessaloniki, there hasn’t been a platter of squid or quaint fishing boat in sight. Instead, road signs warn of bears, rusty pick-up trucks chug along carrying everything from beehives to precariously perched goats, and unending forest has replaced the ocean.

I’ve come to the Northern Pindos National Park where just 4,000 people populate 200,000 hectares of pristine mountains, rivers and forests. My base is Aristi Mountain Resort, a world’s-best, sustainably-minded lodge hovering above one of the Zagori region’s 46 carefully-preserved stone villages.

RELATED: Tracing Greece’s youth ‘hippie trail’

Breakfast comes with a view of one of nature’s most enchanted playgrounds. Astraka’s craggy peak looms and a dark slash in the forest reveals Vikos Gorge, a 20-kilometer long, 400-meter wide ravine (the world’s deepest according to the Guinness Book of Records).

Hairpin bends glimmer in the distance, winding up to the three Papigo hamlets where a smattering of stone cottages and family-run vineyards peter out into ancient trails. Trails that lead to some of Greece’s highest summits, the mysterious Drakolimni lake, and the translucent Voidomatis River. I’m at once fixated yet itchy to play.

Having been abandoned by residents in the 1960s, the remote and overgrown village of Old Perithia on Corfu is one such place. Thanks to The Merchant’s House guesthouse and resident beekeeper Vasili’s “calm, tourist-friendly bees”, the settlement is being given a new lease of life. In Crete, the rising popularity of agriturismos (agricultural tourism) has saved the hinterland’s farms from near-extinction, while over on Ios, Angelos and Vassiliki Michalopoulos have been purchasing land since 2003 to ensure tourism enhances rather than hinders conservation efforts.

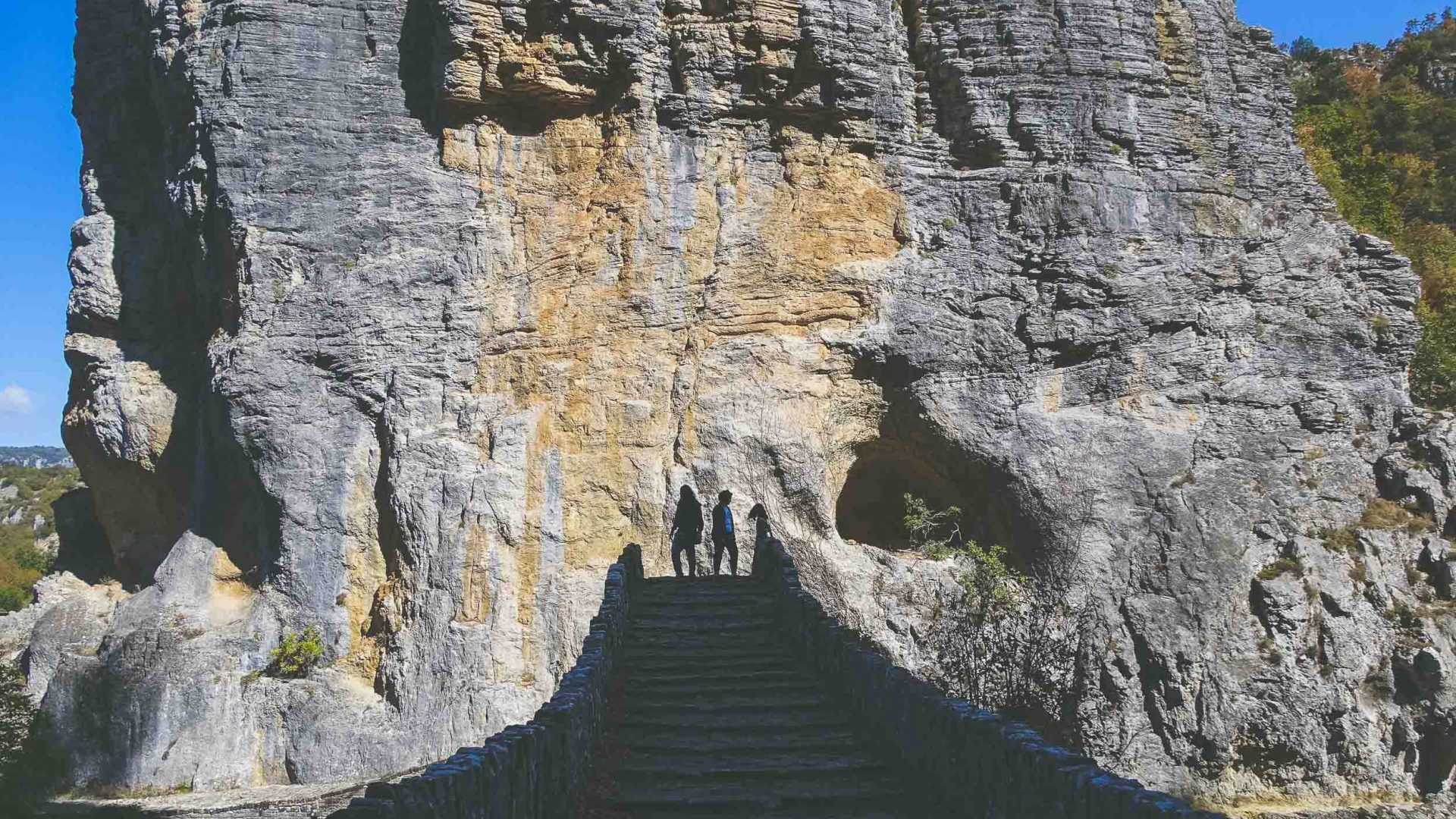

Here, strict building regulations across Zagori makes it remarkably free of modernity. Until the 1950s, there were no roads at all; only 200-year-old stone bridges and cobbled paths, which now provide trekkers with endless trails.

Local mountain guide Apostolis Demertzis drives us up towards a ledge overlooking Vikos Gorge, pointing out villages that are almost invisible to the untrained eye. “Even just a mile away, it’s impossible to see them,” he says. “Built from the mountain rock, the villages look like natural scars across the mountainside.”

In the 15th century, when the rest of Greece was subjected to Ottoman rule, Zagori maintained some autonomy. Merchants looking to trade freely were drawn to the area and by the 18th century, their riches flooded in, building bridges, footpaths, schools and mansions.

The builders of Zagori’s 108 stone bridges took their secret craft all over the Balkans and, as Apostolis puts it when referring to the three-arch bridge at Kipi that took 51 years to build (because the river washed it away every winter), “rich men got greedy”. Free of Ottoman oppression, this tiny region became a beacon of Greek culture—home to enlightenment scholars and the ‘Vikos doctors’, who used local herbs to advance medicine.

RELATED: Welcome to Africa’s secret summits

I ask whether or not the region’s remoteness is its greatest asset. “Yes and no”, answers Apostolis. “The last great exodus to the cities destroyed the area. There was no-one left. Although things are changing.”

In 2009, a new road connecting the ‘spine of Greece’ reduced the seven-hour journey from Thessaloniki to just three, which has helped. Throughout my trip, I get an acute sense of how important tourists are here. Apostolis isn’t the only one to point out that since the recession, some young people are returning in the hope of a simpler and more affordable existence.

Swathed in golden-hour sunlight, we plod back to Aristi behind a shepherd as his flock tumble lethargically down a small lane. Unlike the toothless, stocky shepherds we’ve crossed paths with all day, his youth, jeans, sunglasses and trainers feel incongruous.

I wonder if he’s fresh out of the city, and whether one day we’ll all retreat to the land. I ask Apostolis if he’s here to stay. “These mountains are infectious; I don’t ever want to be anywhere else,” comes his response.

It’s a sentiment that sounds as familiar now the tinkering of cowbells. Once these mountains are in the blood, it takes an awful lot to get them out.

—-