Life had been a grand adventure for Patrick Leigh Fermor, one of the 20th century’s most celebrated travel writers. So what was it about a remote Greek village that made him stop traveling?

In the early 1930s, an 18-year-old British aristocrat left the conveniences of a comfortable life to journey from the Hook of Holland to Istanbul—on foot and horseback, by train and automobile.

He captured the sights, smells and sounds of a Europe the Nazis were casting to oblivion. And when World War II engulfed the continent, this daredevil didn’t just watch Hitler torture it from the sidelines; he enlisted in the British army, landed on the Greek island of Crete as an anti-Nazi secret agent, and disguised himself as a shepherd under the name Kyr (Mr) Michalis to help locals kidnap a German general. This episode even inspired a Hollywood movie, Ill Met By Moonlight (renamed Night Ambush).

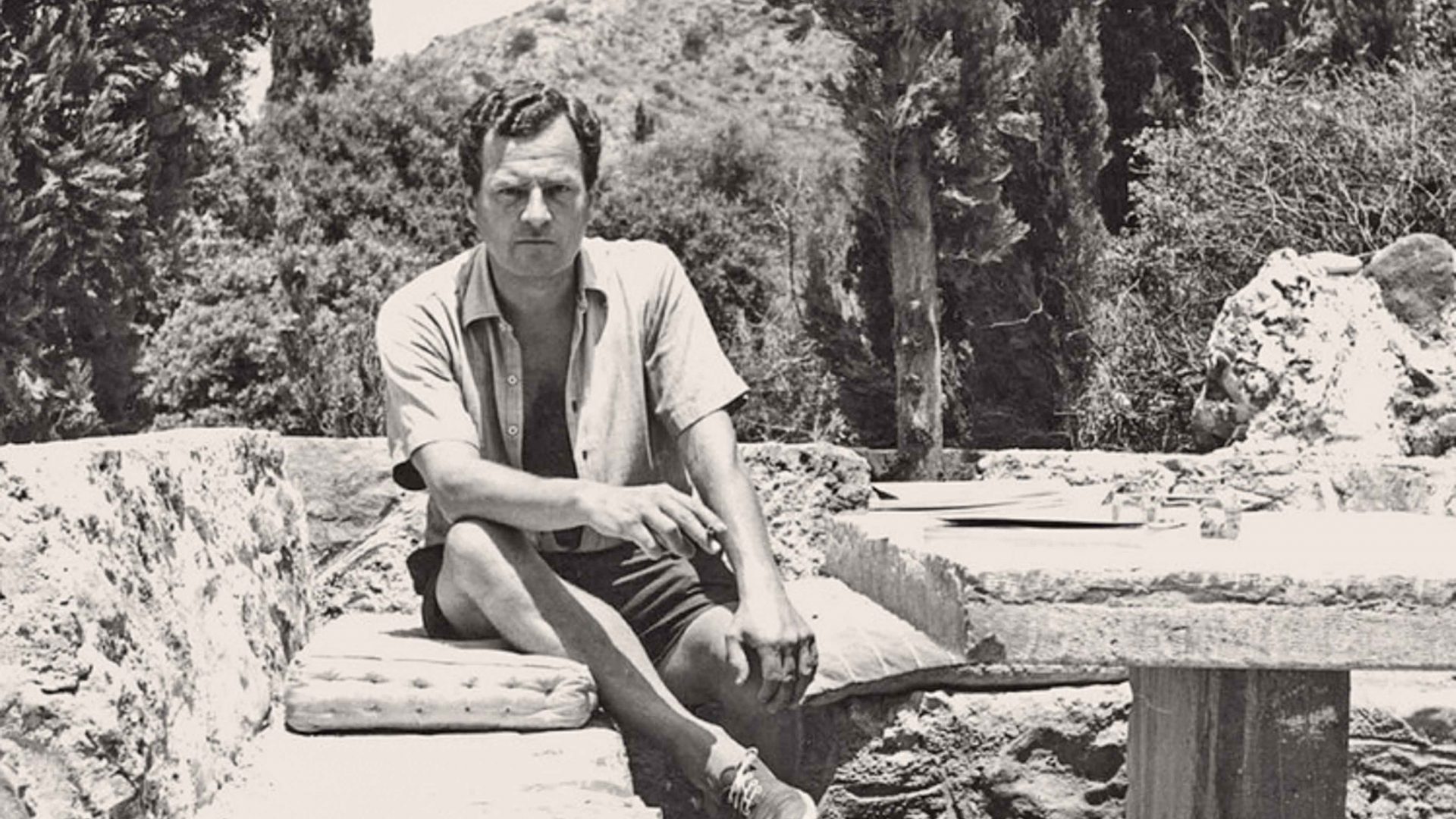

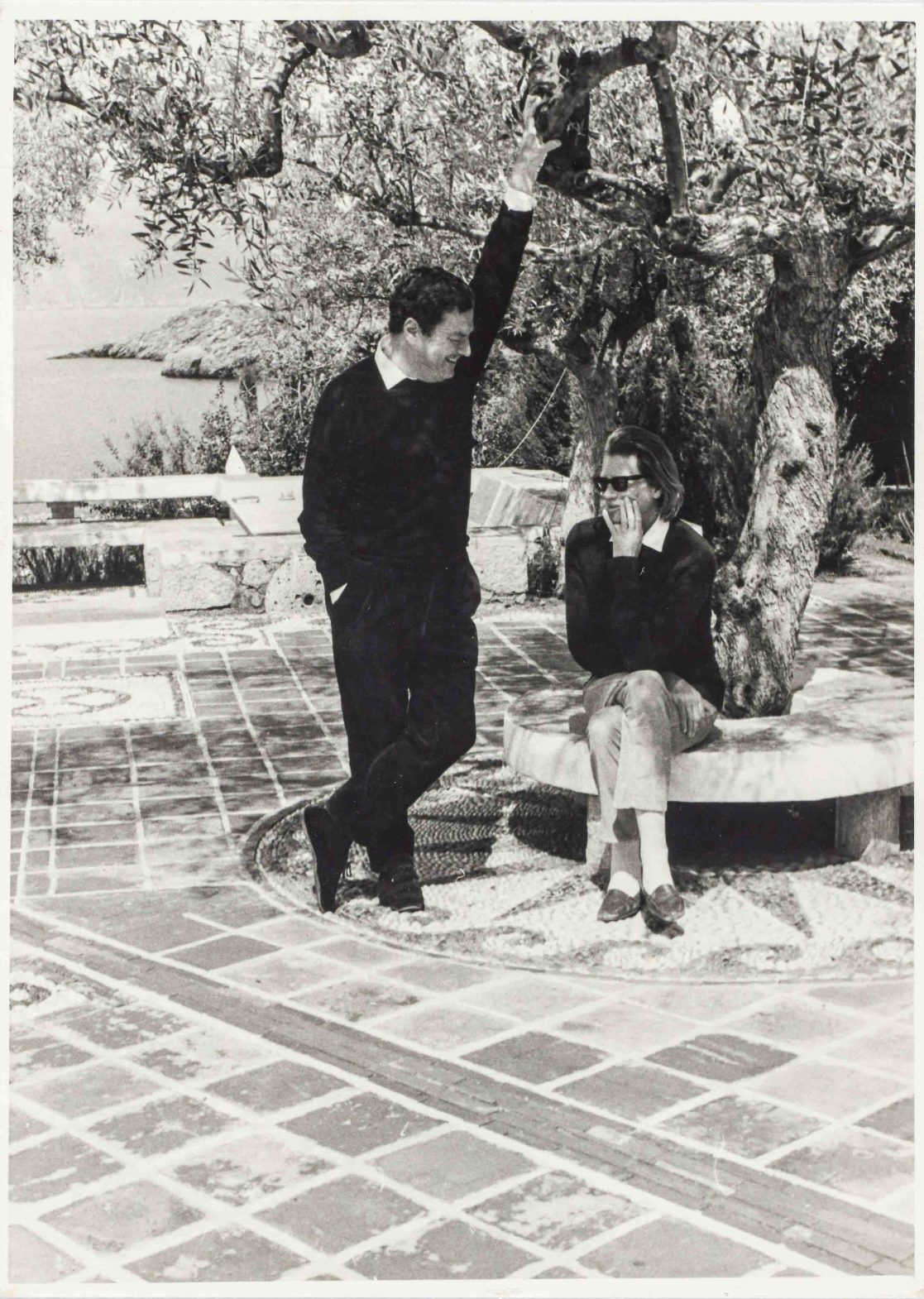

This restless romantic was Patrick Leigh Fermor. Described by one journalist as “a cross between Indiana Jones, James Bond and Graham Greene,” he is, for many—myself included—the 20th century’s most distinct travel writing voice. And the place he eventually called home until his death in 2011 is even more special for it.