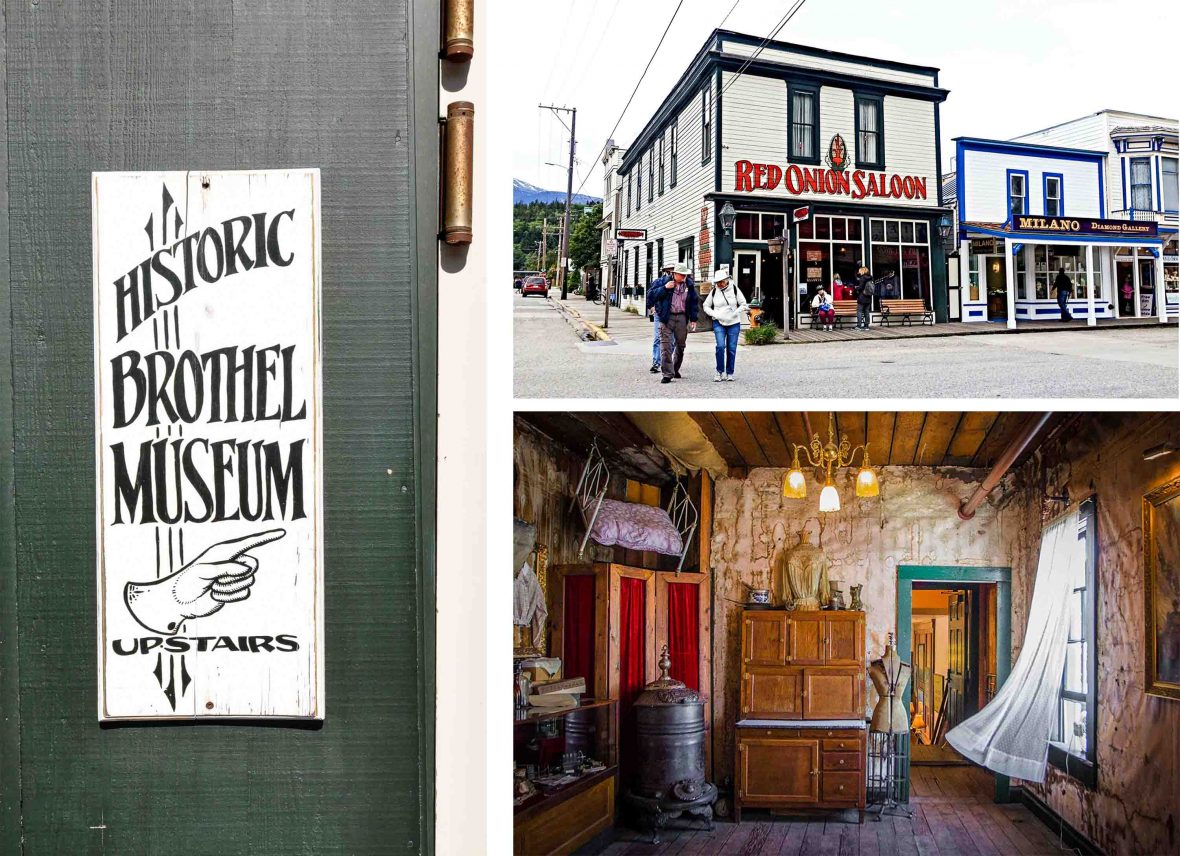

Once the heart of America’s Gold Rush frontier towns, only a handful of genuine saloons are left standing. During a road trip across the States, Shoshi Parks finds much more than just beer and liquor inside them—she finds a window to the country’s past.

The wind is howling when I park my car on Leadville, Colorado’s, main drag. Once a boomtown, first settled as part of a gold and silver mining rush in the 1850s, the now-quiet historic corridor is all but abandoned on this Monday afternoon.

I’ve barely crossed the street before the hail begins, massive balls of ice hurtling from the sky. Covering my head with my jacket, I run for the closest open door: The Silver Dollar Saloon.

I didn’t come to Leadville specifically for The Silver Dollar, but it was high on my list of things to see. Opened sometime before 1879, around the time mining fever took hold of this mountainous region of Colorado, the saloon is famous in certain circles of liquor-loving history buffs.