Tbilisi, the Caucasus’ proverbial melting pot, is reaching a boil—and that’s good for locals and tourists alike, finds reporter Alex King on an Intrepid tour of the region.

Tbilisi, the Caucasus’ proverbial melting pot, is reaching a boil—and that’s good for locals and tourists alike, finds reporter Alex King on an Intrepid tour of the region.

There’s a distinct energy to Tbilisi nightlife these days. We’re sipping beers in a corner of an old Soviet-era power station that has been transformed into the HQ of Mutant Radio.

Old electrical cables and insulation hang precariously above us in an open-air space between tall, flaking concrete walls. A DJ is playing to a swelling crowd, while inside a caravan at the other end of the space, a live internet radio show in solidarity with the emerging protests in Iran is being broadcast.

It’s the evening before Tbilisoba, the Georgian capital’s annual celebration, which has returned after a two-year hiatus to a city both energized by the rebound of nightlife and apprehensive about instability in the region. Three countries that border Georgia are currently at war: Russia, Armenia and Azerbaijan. Ukraine lies on the other side of the Black Sea and the Iranian border is just over 500 kilometers away. Georgia’s population has ballooned as Russians and Ukrainians (in much smaller numbers) have fled here to escape conflict. Tbilisi has re-emerged as the Paris of the Caucasus, a peaceful sanctuary and cultural center for the region.

We’re in Tbilisi with Intrepid Travel on their Premium Azerbaijan, Georgia & Armenia tour. This journey through the Caucasus and three very different post-Soviet states has been an eye-opener, not least due to the timing of the trip. The day we cross the border from Azerbaijan into Georgia, there are kilometers-long queues at Russia’s border with Georgia, as tens of thousands of Russians make last-ditch attempts to avoid military mobilization.

We haven’t experienced a city brimming with such energy since before the pandemic, if at all.

Walls across Tbilisi are covered in responses to what’s happening. In fact, there’s a banner hanging from the wall above us that reads: By entering the territory of Mutant Radio you agree that Putin is a war criminal, Russia is an occupier and you respect the territorial integrity of Georgia, Ukraine and any other country that fell victim to Russian occupation.

Nursing our beers and looking out over this mixed crowd of Georgians, Russians, Lebanese, likely Ukrainians and a host of other nationalities too, in a strange way, it feels like history is being written before our very eyes. We’ve never felt such a powerful connection between what we’ve learned on this tour and what we’ve seen around us. Guides’ thoughtful explanations of the forces that have shaped the region’s history, culture, architecture, economics and politics have filled some important gaps in our understanding. But the most fascinating part of the trip is that these forces clearly continue to shape life across the region today—and this is evident on the streets of Tbilisi.

As we explore the city on foot the next morning, our Intrepid leader, Mariam, explains how Tbilisi was destroyed during the Persian invasion in 1795 and most of what we see in the city today was built in the 19th and 20th centuries, often upon the foundations of earlier buildings.

It’s not long before we stumble across the energy and hubbub of Tbilisoba in Giorgi Leonidze Park, dedicated to the Georgian poet who wrote about the natural landscapes and romance of his native Kakheti, Georgia’s winemaking region—and whose giant bronze statue watches over the park today.

Tbilisoba takes place each October and is a celebration of Tbilisi’s history and diversity, with open-air traditional music concerts, dancing displays, cultural exhibitions and children’s activities spread throughout Old Tbilisi, the historical city center. Tbilisoba was first held in 1978 but integrates elements of the much older Rtveli (grape harvest festival) celebrations, traditionally accompanied by feasts, musical events and traditional costume and dance.

For a number of reasons, 2022’s Tbilisoba is unlike any other. Locals complain to us that pandemic restrictions took a heavy toll on Tbilisi’s famous culture and nightlife. In fact, many of the city’s most recognized cultural institutions, such as the iconic Bassiani nightclub, decamped across the border to Armenia, where Covid restrictions were much more lax. There’s a homecoming feel for late 2022 as Tbiliselebi (people of Tbilisi in Georgian) come together for the first time to celebrate the city’s post-pandemic reawakening. An influx of recent guests adds another layer of energy.

Since the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine nearly a year ago in February 2022, at least 40,000 Russians have settled in Tbilisi, which has a population of just over a million. Some estimates put the numbers much higher. While this unprecedented flow of Russians has created some tensions, many of the new arrivals are activists and artists critical of Putin’s regime, who have made a noticeable cultural contribution to their adopted city—from sets by Moscow’s best techno DJs to opening new queer spaces and parties.

Mariam stops us at the edge of Orbeliani Park, where there’s a sprawling reconstruction of Old Tbilisi with its bustling markets, bakers and traders, stacks of traditional ceramic wine jugs and small urban farms, complete with goats and geese. Around the corner, there’s a big stage looking out over a road lined with stalls selling traditional Georgian food and crafts for sale.

The street is packed with people enjoying the festivities. Many of the younger women are wearing traditional floral peasant headdresses. As Mariam leads us deeper into the old town, she explains how many great powers fought for control of this city throughout its long and rich history—the Roman Empire, Sassanid Persians, Muslim Arabs, the Byzantine Empire, the Seljuk Turks, the Russian Empire and the Soviet Union—all leaving their mark on its culture and architecture.

Tbilisi has historically been a tolerant and cosmopolitan mix of populations. Today, on Vakhtang Gorgasali Square by the river, there are traditional displays from Tbilisi’s significant minority communities: Ukrainian, Greek, Armenian, Assyrian, Polish, Jewish, Azeri and many more. Alongside historic Georgian Orthodox churches, Tbilisi hosts a synagogue, mosque, Zoroastrian temple and churches for an array of Christian denominations. It’s exciting to feel co-existence and cultural exchange still happening around us.

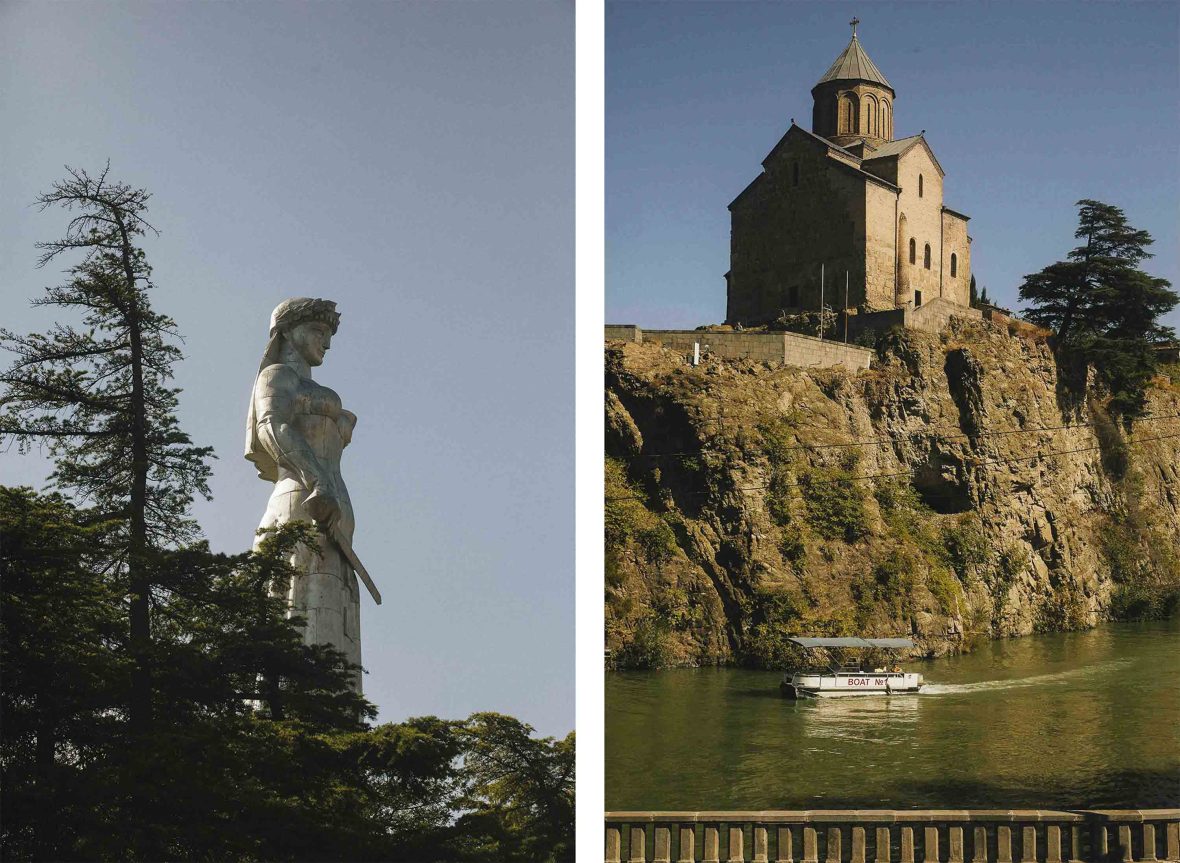

We take the cable car up to Sololaki Hill for a grand view of Tbilisi. The Mtkvari River winds elegantly through it, with the Georgian Orthodox Metekhi church and statue of King Vakhtang Gorgasali, who founded the city in 458, on its left bank. From Sololaki, the 20-meter-tall Mother of Georgia statue stands watch over Tbilisi, with a bowl of wine in one hand and a sword in the other. Unveiled in 1958 for Tbilisi’s 1,500th anniversary, Mariam explains that she represents the character of Georgian women and the Georgian nation: hospitable to those who come as friends but unafraid to resist anyone who comes as an enemy.

On this warm autumn afternoon, the courtyard at Fabrika is full of people enjoying local craft beers or tapping away on laptops with coffees by their side—many of these recent Russian arrivals. Yet inside the bars and cafés are warning signs that read ‘Russia is an occupant’ and explain in English, Georgian and Russian that Russia occupies 20 percent of Georgian sovereign territory through its de-facto control of the unrecognized ‘breakaway republics’ of Abkhazia since 1993 and South Ossetia since 2008.

“It’s very important for the queer community to explore culture because unfortunately queer activism here is very difficult right now. We’re trying to find a way to do our activism, be safe and not make people crazy around us.”

- David Apakidze, artist

Tbilisi’s art scene has long been politically charged and cultural spaces and walls around the city are covered with responses to the Ukraine invasion.

Founded in 2020, queer art collective Fungus Gallery hosted its first group show in April 2022 focused on Ukraine—with a follow-up show in Kyiv. “We try to make political art and speak about gender and other issues important to us,” explains artist David Apakidze. “We’re working on a group show about the experience of Russian colonialism in our region, which is currently in a very strange position. We want to invite artists from Azerbaijan, Armenia and across the region to express themselves through our Tbilisi-based platform.”

The exhibition we visit is Tragedy of the HEROmachine: You and Me on the Brink of Extinction by multimedia artist Lasha Kabanashvili. The exhibit explores consumer society, post-humanism, queer theory and cyberfeminism. While some Russian arrivals have organized new queer events, Apakidze explains rents have doubled across the city, making life even more difficult for local artists, students and working-class people. Queer artists and activists in Georgia have faced intense hostility in recent years, with politicians often stoking the flames of homophobia to further their political programs. So, the queer community has largely redirected its efforts from overt, western-style queer activism to cultural initiatives and joining universal struggles.

“It’s very important for the queer community to explore culture because, unfortunately, queer activism here is very difficult right now,” Apakidze explains. “We’re trying to find a way to do our activism, be safe, and not make people crazy around us. There are so many problems that queer and straight people share: hunger, lack of healthcare, and cost of living.”

Apakidze recommends the nearby Why Not Gallery, where the main exhibition space’s floor is covered with sand and hand-painted wallpaper peels from the walls, echoing the seaside and abandoned houses of Abkhazia. Both artists on display are Mengrelian refugees from Abkhazia. This exhibit is titled Painted Walls Create an Illusion of Reality by Mari Aqubardia. Further inside the space, Charitskhes, De? by Nika Qutelia is a collection of digital and video art, exploring the idea of changing places and restarting life from scratch.

“The war in Abkhazia has turned into myths and legends and everybody has their own interpretation: my generation knows almost nothing about the conflict,” explains Aqubardia, who first returned to her family home in Abkhazia at age seven and started spending summer holidays there. “As a child, I was learning and witnessing more about the war than any kid should.”

Aqubardia explains that it’s still difficult to discuss the Abkhazia war in art, so she chooses to do so indirectly, through her own abstract lens of memory. “I liked wandering around and observing abandoned homes in the neighborhood,” she says. “The image of nature in the looted, derelict, war-torn houses would toss me into a stream of dreams, creating an illusion of peace and a dandy life. I turned into a collector of memories: my childhood memories assembled in a chest. The process of translating these memories into art takes a lot of emotional resources from me. Once opened, an infinite number of stories spread out into visual scenes; stories that are connected to two contradictory emotions—which is why I titled my previous series Tears of Sadness and Joy.”

After the sun sets, the Tbilisoba festivities are in full swing: there’s a heaving crowd swaying to music from the huge stage on Europe Square and the adjoining Rike Park is jam-packed with families enjoying barbecues. There are lots of Russian voices to be heard, alongside Georgian and some English. The atmosphere is buzzing but good-natured—everyone is just out to enjoy themselves. After a short walk along the river, we stumble across a DIY gallery space hidden in the pedestrian underpass on Nikoloz Baratashvili bridge. This surreal concrete cavern was once Tbilisi’s first Soviet-era jazz club, which opened in 1975 but after 15 years, lay empty for three decades.

The space recently reopened as Tato Art Bridge, a gallery space, bar and concert venue, masterminded by Anny and Geo from Georgia and Gary, originally from the UK. Gary used to live in Moscow with his wife, who was born in Abkhazia. They moved to Tbilisi after the invasion of Ukraine, along with many other Russians from the art world, such as Varya Pavlova, aka Lisokot, a formerly Moscow-based conceptual singer and poet, who’s here preparing for her upcoming performance.

“Tbilisi has attracted the crème de la crème of Russia’s art and activist world: dancers, classical musicians and DJs,” Gary explains. “The Russians who left early on were the more open-minded and artistic types. We have big plans to develop this space as an internet radio station and cultural bridge, bringing Georgian creatives together for collaborations with outsiders. Tbilisi has always been open to a vibrant mix of people. It’s that famous Georgian hospitality: come in peace and you’re welcome.”

We haven’t experienced a city brimming with such energy since before the pandemic, if at all. It’s thrilling to be here during this moment of celebration and change: the melting pot of Tbilisi is very much on the boil right now.

There are many reasons to feel fearful about the region’s future. But what we’ve seen in Tbilisi has given us many more reasons to feel hopeful. The tensions are palpable but young people, artists and activists from across the region are coming together, opening new dialogues and creative networks. In their hands, the future for Georgia and the wider region will be one shaped more by culture and collaboration than conflict.

Alex and Ossi traveled on Intrepid’s 15-day Premium Azerbaijan, Georgia & Armenia itinerary. Head to intrepidtravel.com for more information and the full range of itineraries.

***

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: