Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

Forest bathing: It’s more about mental and physical restoration than it is shampoo and rubber duckies. Amanda Ogle dips her toes into this Japanese-born phenomenon.

I’m holding a sprig of cedar and a small note in my hand as I stand at the edge of a dense forest.

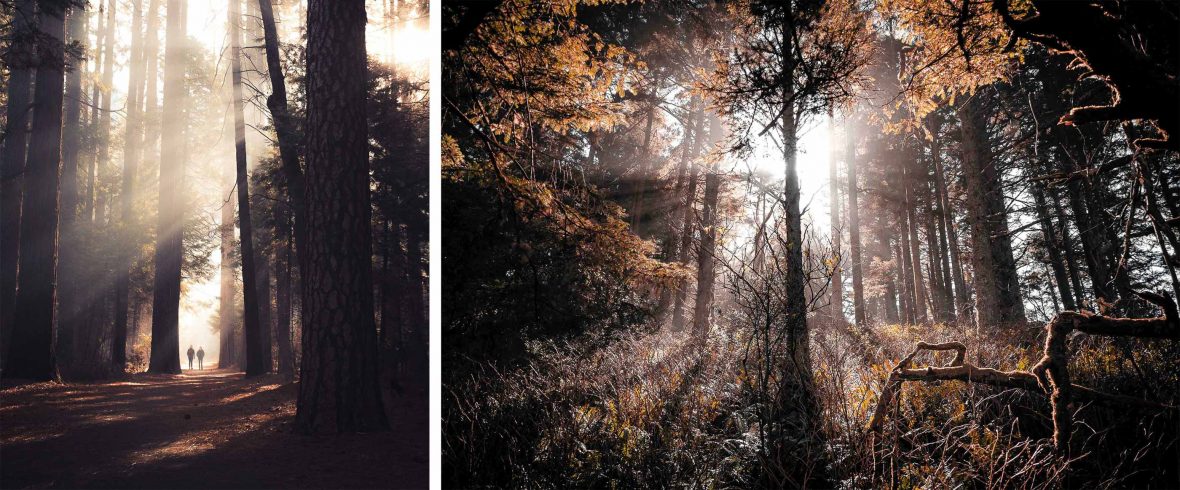

The forest, on Oregon’s coast, is where I’m experiencing forest bathing—or shinrin-yoku as it’s known in Japan: The practice of going into the forest in search of mental and physical healing.

Before entering the forest, or “threshold” as my guide, Erin Bowman, calls it, she encourages us to place an offering of some kind—our sprig of cedar, a tiny pinecone, or whatever speaks to us —on the ground. The offering is a gift to nature for letting us enter. I place my cedar sprig neatly on a pile of greenery in front of me, then step into the forest ahead.