When American writer Ariel Sophia Bardi discovered she was eligible for Italian citizenship through her great-grandfather who had settled in Baltimore, it led her to a tiny, seemingly undiscovered village in Italy.

In 1913, Giulio Bardi—my bisnonno, my great-grandfather—disembarked from a transatlantic ship at the Port of Baltimore. After many gray days at sea, he arrived on a hazy, lusterless morning. At least, that’s how I imagine it; it may well have been a bright afternoon.

I picture the young Italian, stocky and lantern-jawed, lined up with other men on the docks. They look unshaven and slightly shell-shocked. Seagulls screech and oil-swirled saltwater laps the pier. Giulio opens a battered suitcase for inspection, dark eyes glinting with the light of a new world.

In reality, I don’t know much more than names and dates. I knew the Bardis were a prominent Renaissance banking family, but until I started tracking my great-grandfather’s immigration papers, I knew very little about my origin. And with family stories focused on a distant golden age, it never occurred to me to wonder what our last Italian relative had actually left behind.

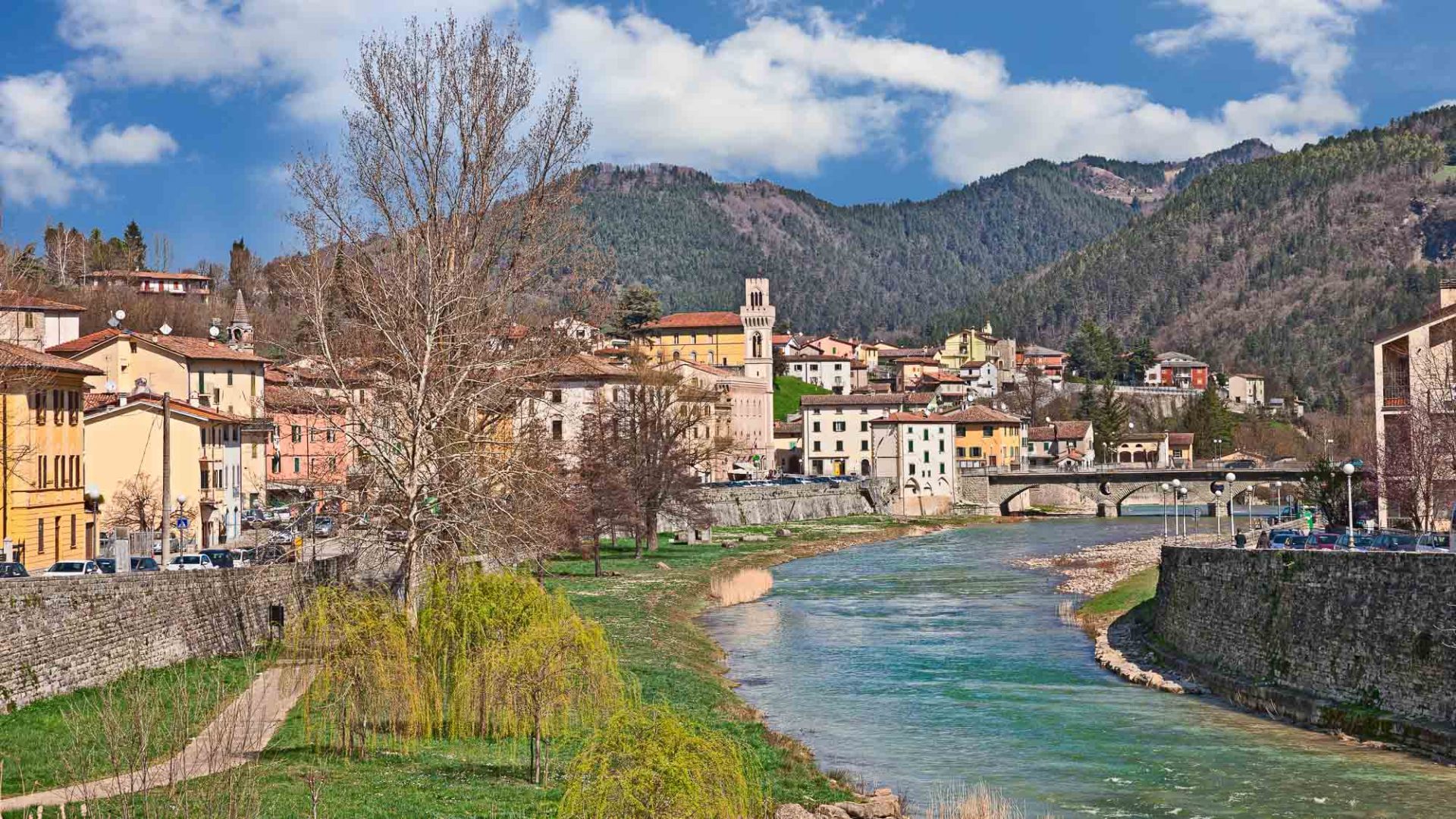

“Lots of Bardis come from here,” the dark-haired woman checking me into the hostel tells me. I set my bags down in a sparse vaulted room then head back out to explore the town. Across the river is the old quarter, Mortano, which remained a separate village until 1923. It began as a Roman-era settlement and in Renaissance times (between the 14th and 17th centuries) it housed a noble palace. Much later—in 1888, to be exact—it was also where my great-grandfather was born. A cousin told me he lived above a barn owned by the church and worked on their farm.

Up a sloping hill, illuminated by the late afternoon sun, I round a corner and spot an old, moss-covered church—and next to it, a barn. A fat, prowling cat with pale green eyes stalks the roof. I feel a frisson of discovery.

RELATED: Finding tranquility in an alternative Iceland

The genealogical thrills I had come for were proving easy to find. But what I hadn’t counted on was the allure of the village itself. With the sherbet sunset streaking the sky, I eat a plate of gnocchi overlooking the Bidente River, which runs the length of the town. A sculpture park skirts the water on either side. And though off-the-beaten track, Santa Sofia is an arts and gastronomy hub. Each meal I have is proudly regional—and mouthwateringly sensational. During the next day’s lunch of grilled offal sausage (ciavàr), baked eggs with truffle, and pear arugula salad with a sprinkling of parmareggio, I all but forget my original mission.

Luckily, the village comune, or municipality, is close at hand. The young, friendly clerk is, serendipitously enough, named Giulia. I inquire about Giulio Bardi’s birth record and steel myself for a long wait. She will no doubt climb a ladder through some dusty, neglected archive and emerge sneezing, hours later, tattered tome in hand. Within minutes, she hands me a crisp print-out of the certificate, signed and sealed: Mission accomplished.

I doubt my great-grandfather could have foreseen that I would one day follow his footsteps in reverse. But I give silent thanks for the opportunity, looking forward to taking one last stroll around our family’s rediscovered village.

Giulia still seems confused as to why I came in for the copy. Nervously, I explain the citizenship application package, and wonder aloud if I’m the first person to make such a request. Talk about unchartered territory.

“No, no,” Giulia laughs. “Plenty of people ask me for this,” she tells me in Italian, sounding out each word for my benefit. “But they usually do it by email!”