In Texas, the story of the state’s most beloved dish—chili con carne—meets at the intersection of tradition, culture and immigration.

In Texas, the story of the state’s most beloved dish—chili con carne—meets at the intersection of tradition, culture and immigration.

Mi Tierra Café y Panaderia on San Antonio’s historic Market Square, the largest Mexican-entrenched plaza in the United States, is a place so perfectly realized and fully colored-in it feels like stepping into a Frida Kahlo painting.

It is festooned with piñatas, papel picado (handmade, Mexican bunting), decorative murals and Día de los Muertos altars laurelled with magnolias and cornbread—and when you hear its harmonizing in-house mariachi band, you can’t help but rush headlong inside. It is a kaleidoscope turned inside-out, and since opening in 1941, it has served the people of the city 24 hours a day, every day of the year.

“This is the magic kingdom of Tex-Mex,” says the restaurant’s third-generation co-owner, Pete Cortez, with infectious energy. “Market Square was originally meant to be a parking lot, but my grandfather Pedro’s vision transformed the area and my grandmother Cruz supplied the recipes for the first restaurant here. It’s part of Texan history and now a symbol of San Antonio foodways.”

For those not familiar with the fastest-growing city in the United States—or one of only two places in North America to be recognized by UNESCO for its culinary heritage—San Antonio supports the world’s greatest concentration of Tex-Mex restaurants. At best guess, there are around 1,000 cantinas and cafés.

Inside each one is a soul that can’t be easily replicated, and one dish above all that has become synonymous with the city: Chili con carne. It is a story of family, community and home, but mostly, it’s a story of immigration.

“Before the arrival of the Spanish, local tribes ate spices used in chilli con carne, but the biggest change was the introduction of invasive species, like cattle, goats, sheep and pigs as a food source.”

- Bruce Shackelford, curator

Common understanding has it that the roots of Texas’ official state dish came to San Antonio before the bloody Battle of the Alamo in 1836, even as early as the 1700s, some food historians say.

The claim is the recipe was borne on masted ships sailing from the Canary Islands across the Atlantic and carrying some of the first settlers of the modern United States. At that time, Indigenous islanders were enticed to move to what was then part of Mexico as a bulwark against possible French expansion across Texas.

The part of the story most aren’t familiar with is they brought with them a heavy-handed approach to using comino molido, or dried cumin. Things changed dramatically, of course, when it became used for chili con carne.

But a visitor to San Antonio will also hear stories of Mexican cattle herders, or vaqueros, who arrived with saddlebags of chili ancho, garlic and Mexican oregano, also now staple seasonings in the blue-collar dish.

A visit to the Witte Museum in Brackenridge Park also reveals it was the Spanish who brought about the most influential change. To feed more converts to Catholicism along the Mexican frontier, the area’s religious Missions—now such a historic part of Downtown San Antonio—raised livestock as a vital food source. And so, chuck beef was added to people’s diets, and ‘chili’ had a ‘con carne’ bedfellow for the first time.

“Before the arrival of the Spanish, local tribes ate spices used in chili con carne, but the biggest change was the introduction of invasive species, like cattle, goats, sheep and pigs as a food source,” says Bruce Shackelford, Texas History Curator at the Witte Museum. “All of these animals were raised at the missions, and what came next was stews of all kinds as a way to feed more people.”

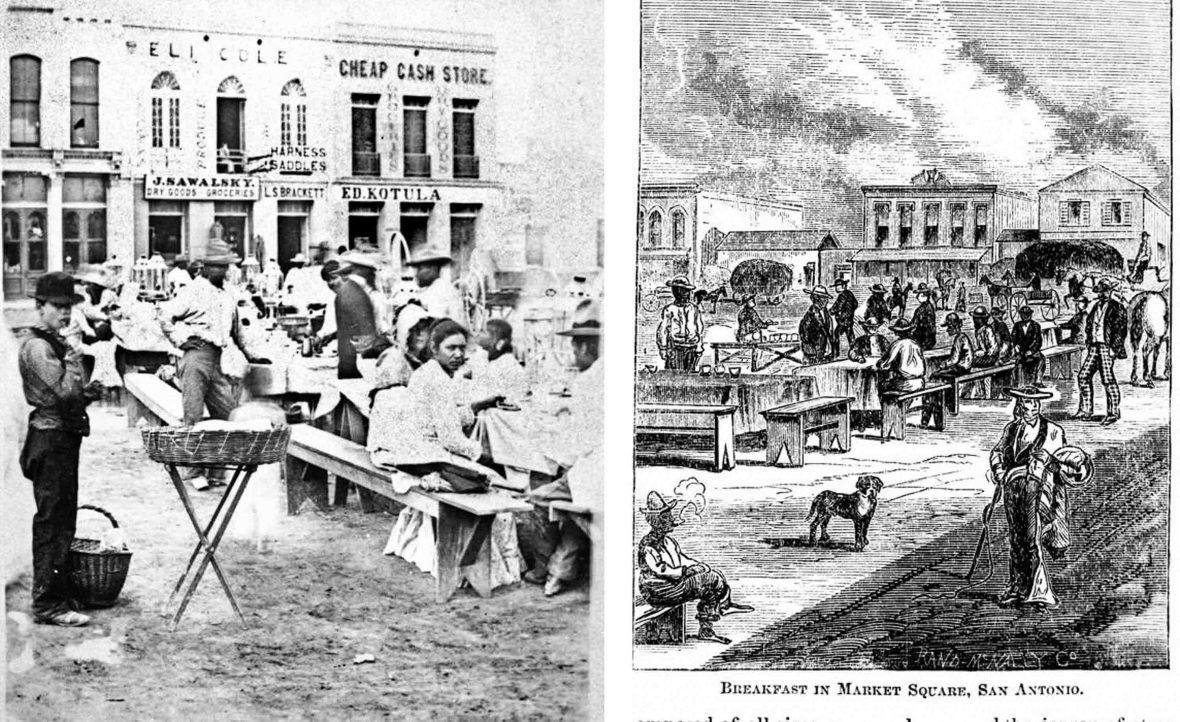

It was around this time in the early 1860s when the ‘Chili Queens’ first introduced their take on chili con carne to San Antonio’s newfangled fabric of residents.

The city’s connection to the interstate railroad for the first time saw it besieged by new arrivals—and, like anywhere, this provided an opportunity to make money by selling cheap street food.

“Every dish here tells the story of our forefathers and foremothers, and our diners are now part of our extended family. They’re loyal—more than that, friends—and many come every day to eat with us. So chili con carne continues to bring San Antonio together.”

- Diana Barrios Trevino

“The first Chili Queens made pots of the hot stew at home and brought them to the plazas in San Antonio to serve usually with smoking hot tortillas,” continues Shackelford. “The press and the numerous writers who passed through San Antonio then romanticized their evening on the plazas in print. Back then, San Antonio was an exotic place to be for a visitor from New York or Boston. And still, it continues to be.”

Hanging in the Witte Museum today, Thomas Allen’s potent and romantic oil painting ‘Market Plaza’ (1878/1879) captures vaqueros, politicians and impoverished travelers amid nesting hens and cattle carts, yet all congregating together on San Antonio’s Military Plaza, as if finding kinship through bowls of red.

As well as the painting, historic accounts from the time tell of mesmeric plazas that reverberated with the sound of clanking pots and smell of casero (home-style) cooking, with wooden tables dragged onto almost every corner. They also chronicle what happened next: There was a communal desire for these quasi-soup kitchens and evening open-air fare—and the Chili Queens’ reign began.

The stands became so popular that, in 1893, the San Antonio Chili Stand was presented at the Chicago World’s Fair, giving many Americans their first taste of chili. Unlike the chili con carne known today though, the Texan original was different: It lacked any kind of luxurious bean or tomato, and was primarily made of dried pepper paste and chuck steak.

Yet still, the dish went on to conquer the nation. What’s more, for those chili conquistadors back on San Antonio’s plazas who continued cooking for workers long through the Great Depression, it might have seemed like the piquant aroma from their pots had blown right across the country.

More than a century later, chef and restaurateur Diana Barrios Trevino best represents the Chili Queens’ culinary legacy today, having experienced so much of San Antonio’s growth first-hand. Growing up in the kitchen run by her mother Viola, who immigrated from Bustamante in Nuevo León, Mexico, she remembers food being “driven by family and community.”

“My mother felt it in her heart that a restaurant life was something she wanted for our family,” she says. “So it was only a matter of time before Los Barrios was born.”

That Tex-Mex restaurant, first opened in 1979, now has three siblings serving a rich, piquant chili con carne in all its glory across the city. Its shared philosophy— ‘amor, fe y alegria’ (love, faith and joy)—is something Trevino says is now deeply embedded in the city’s DNA: “Every dish here tells the story of our forefathers and foremothers, and our diners are now part of our extended family,” she adds. “They’re loyal—more than that, friends—and many come every day to eat with us. So chili con carne continues to bring San Antonio together.”

This is a simple truth behind the longevity of evocative restaurants like Los Barrios and Mi Tierra Café y Panaderia and the myth of the Chilli Queens. People queue not just for chili con carne in all its hot takes, but for a bite of nostalgia, one forkful at a time.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us anytime at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: