The story of how Earth Day forged the modern environmental movement, from one of the founders himself: Denis Hayes.

The story of how Earth Day forged the modern environmental movement, from one of the founders himself: Denis Hayes.

One of the best things about the history of Earth Day, when you really have a close look, is that the world’s most participated-in secular holiday began as a grassroots effort of just a handful of people.

The build-up to the first Earth Day, which took place in the United States, was one of growing concern over environmental degradation and increased youth activism in the country. Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, which details the harms pesticides have, made waves among those who didn’t often think about environmental stewardship. And years of Vietnam War protests on college campuses had created a generation of young people well-versed in organizing.

In 1969, one year before 20 million people would take to the streets across the US in the first demonstration of the modern environmental movement, the Cuyahoga River in Ohio caught fire, one of a series of blazes resulting from toxic pollutants in the water.

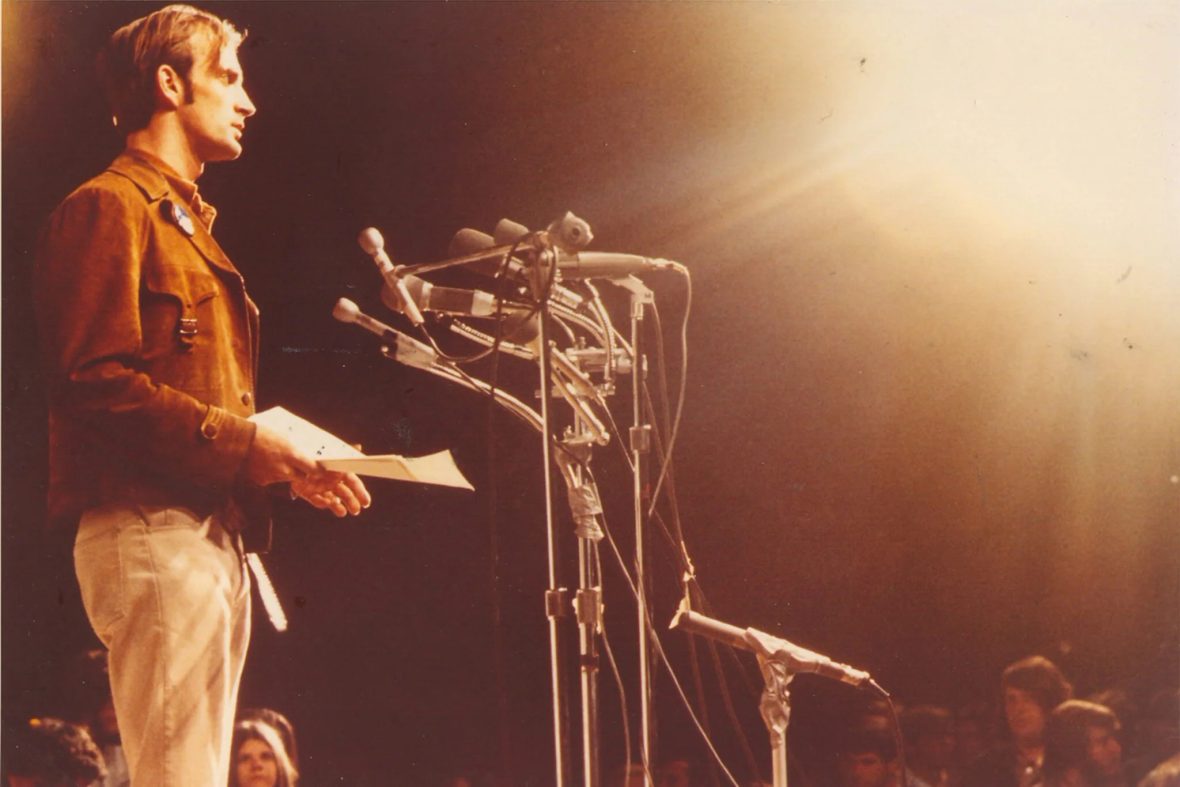

This was the context in which Denis Hayes, a 25-year-old activist and public policy graduate student at the Harvard Kennedy School, picked up a copy of the New York Times one morning that fateful year. On the front page was a story about Wisconsin Senator Gaylord Nelson, who had made a speech calling for a series of environmental teach-ins in the model of the youth-led anti-war movement.

Hayes had been an anti-war organizer as an undergraduate and already decided he wanted to focus his career on environmental issues. But a much more immediate motivation prompted him to get in touch with Senator Nelson: A homework assignment. All the students in the master’s program had to find and work with policymakers outside the university, so Hayes scheduled a meeting and headed to the US capital, Washington DC.

The allotted 15 minutes stretched into hours, and Hayes left with the assignment to organize Boston, the city where he was living at the time. A couple of days later, he got a call from Nelson’s office: Would he be interested in coming on board as the national coordinator for something called Earth Day?

The first Earth Day in 1970 was a roaring success by every metric. Millions of people across the country staged demonstrations advocating for local environmental issues and the broader cause of environmental stewardship writ large.

“It was the fastest set of promotions that I’d ever experienced,” says Hayes. “And it sounded like an awful lot more fun than what I was doing in school.” He dropped out of Harvard to take the gig and recruited a handful of classmates to come along.

In addition to hiring regional coordinators, who were recruited mostly from college campus antiwar activist groups, the brand new Earth Day leadership team reached out to every community and environmental group they thought might have any interest.

“Before Earth Day, there were people who cared deeply about freeways that were cutting through their neighborhoods,” says Hayes. “People cared passionately about the fact that they couldn’t fish in the stream they used to be able to fish from because it was now laced with toxic pollutants. People worried about pesticides. People worried about assaults on whales. All of this stuff was there, but the people who cared about whales didn’t think they had anything at all in common with people who cared about air pollution. And what Earth Day did was take all of those different strands, and—almost without fully understanding what we were doing—weave them into the fabric of modern environmentalism.”

Trade unions have often been positioned against environmental regulations by the argument that regulations will lead to profit losses and layoffs. But organized labor turned out to be an invaluable ally for Earth Day. Walter Reuther, the president of the United Auto Workers union (UAW), was particularly committed to Earth Day and the broader environmental movement. The UAW was Earth Day’s biggest donor, and also printed and mailed all of the newsletters that—absent of Facebook groups or email in those times—were the primary way organizers got the word out to new participants.

As Hayes recalls, Reuther had a different way of looking at things than the car companies that opposed environmental regulations and employed most UAW members. “Reuther told me, ‘You know, last time I flew into Los Angeles, it gave me the impression I was flying into a bowl of split pea soup,’” says Hayes. “‘Americans aren’t going to tolerate it. And these guys in Detroit know how to design clean cars. My guys can build anything that they can design. It’s time to get serious about this or it’s going to kill the automobile industry.’” Turns out, conversations around means of electric transportation have been happening for a long time.

With the turnout and collaboration across the United States and across industries, the first Earth Day in 1970 was a roaring success by every metric. Millions of people across the country staged demonstrations advocating for local environmental issues and the broader cause of environmental stewardship writ large. In the years immediately following the first Earth Day, the newly galvanized environmental movement notched a series of the most meaningful legislation to be enacted in the US then and since, including the Clean Air Act of 1972, the Clean Water Act, the Endangered Species Act, and the formation of the Environmental Protection Agency.

In the 1990s, Earth Day went international. It’s now the most widely observed secular day across the globe. In recent decades, the focus has shifted from the environment to also include climate change.

It’s easy these days to feel like Earth Day has turned into a greenwashing extravaganza, as if it’s a day each year set aside for every corporation to announce that they’re switching to biodegradable straws or giving every employee a reusable shopping bag. But within the history of Earth Day’s origins are lessons for any of us who want to protect the natural world to learn. A couple of our favorites: One, start with the problems close to home; and two, look for solidarity even in places we wouldn’t expect.

The theme for Earth Day 2023 is ‘Invest in Our planet’. Find out more about how you can take action for Earth on the official Earth Day website.

Miyo McGinn is Adventure.com's US National Parks Correspondent and a freelance writer, fact-checker, and editor with bylines in Outside, Grist, and High Country News. When she's not on the road in her campervan, you can find her skiing, hiking, and swimming in the mountains and ocean near her home in Seattle, Washington.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: