Tourists funding their trips by begging for change or selling wares once they reach a destination is becoming a common sight. But is it ever OK to ask other people to help finance your holiday?

This idea that you can travel the world for free, that you can rely purely on the kindness of strangers to fund your adventures and to ensure your survival: It should be a mark of shame. And yet some travelers wear it like a badge of honor. That’s confusing to me.

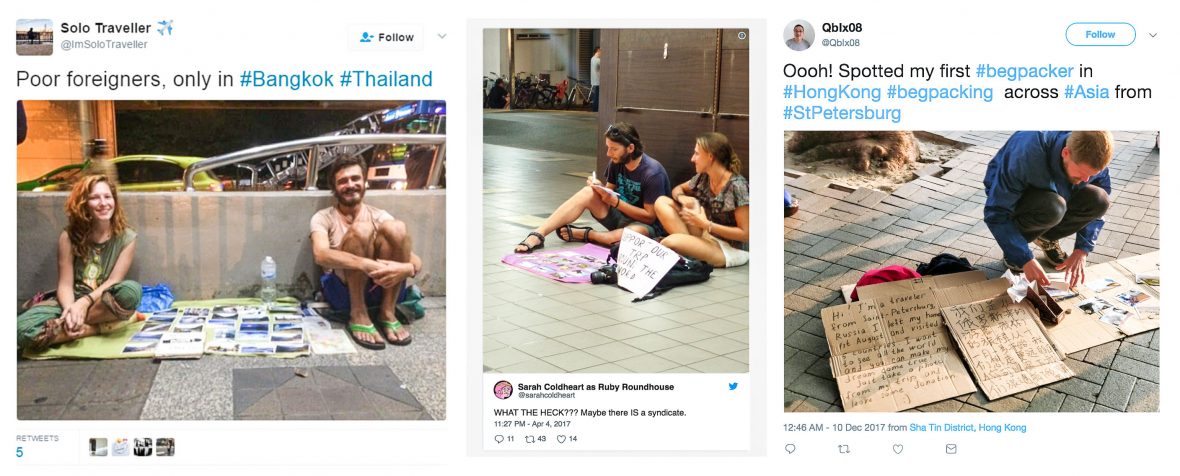

These are the ‘begpackers’, the band of travelers who arrive in their destination with next to nothing, who plan on going cap in hand—to not only other travelers, but locals, too—to help make their way around the world.

It sounds unbelievable. Like, who would have the chutzpah to do such a thing? Who would be able to talk themselves into believing this is a reasonable thing to do?

Some choose to busk, playing musical instruments or selling artworks, which I don’t have so much of a problem with. At least they’re doing something. Others, meanwhile, just put their cap out and expect. They’re openly begging on the streets. They’re starting up GoFundMe and Kickstarter campaigns to fund their travels. They’ve been caught using shower facilities in homeless shelters in Australia; they’ve pinched meals meant for homeless people from Salvation Army food trucks.

RELATED: Is living abroad the ultimate travel experience?

Here’s the begpackers’ boast: That you don’t actually need a lot of money to travel. In fact, you barely need any at all. If you can get yourself to a destination, all it takes is a little creative grifting and you’re on your way. People will help you out.

What that ignores, of course, is the people who are doing the helping. Occasionally, those people might be locals, who may have plenty to worry about without being guilt-tripped into giving to foreign beggars. More often, they’ll be other travelers, those who’ve taken the time and effort to save up for a trip that they’ve paid for themselves.

They saw this as a social experiment, a test of the innate goodness of humankind. And they succeeded in proving it—people are generally willing to help those in need. It might have made for an entertaining TV show, but imagine if every traveler who watched Free Ride decided to head out into the world without a penny to their name. The locals would grow tired of our little social experiment pretty quickly.

RELATED: Has the internet killed the joy of discovery?

The main problem here is that nobody from a Western country should be struggling to survive in the developing world. If you can afford the flights, you can afford to stay home and save for that little bit longer to ensure you don’t have to rely on other people to fund your enjoyment.

There’s a sense of entitlement to begpackers that’s breathtaking. Yes, there are travelers out there who really are down on their luck, and who really do deserve a helping hand. But these poor souls are overshadowed by the vast majority of the begpacking crowd, the types who set out on their journeys with the express intention of relying on the generosity of others so that they can have fun.

That’s hardly a badge of honor.