Travel writer Johnny Motley takes an unexpected journey—literally and historically—through the northern Spanish-influenced Basque country of the American West.

Travel writer Johnny Motley takes an unexpected journey—literally and historically—through the northern Spanish-influenced Basque country of the American West.

At least since Pliny the Elder’s accounts of enigmatic mountaineers on the Roman Empire’s fringe, the Basques of northern Spain have mystified historians. Their language, Euskara, is unrelated to any other tongue on earth, and genetic analysis shows Basques, long isolated in the deepest reaches of the Pyrenees Mountains, might be descendants of Europe’s earliest human inhabitants. Many are surprised to learn Basques were among the first Europeans to explore the Americas. Juan Sebastian Elcano, a Basque ship captain, completed the first circumnavigation of the globe with the Magellan expedition and later became the first European to systematically map the coast of South America.

Mythology and colonial history aside, the American West is today home to one of the world’s largest Basque diasporas. Pulled by jobs as sheepherders and pushed by persecution in the Pyrenees of northern Spain and the coast of southern France, thousands of Basque families immigrated to the Great Basin and the Rocky Mountains in the 19th century. Especially in pockets of Nevada, Idaho, and California, the West’s Basque heritage remains robust and proud. From Boise to Bakersfield saloons serve pintxos (bar snacks) and picon punch year-round, and the exuberant rhythms of trikitixa (Basque accordion) enliven streets during annual Basque festivals.

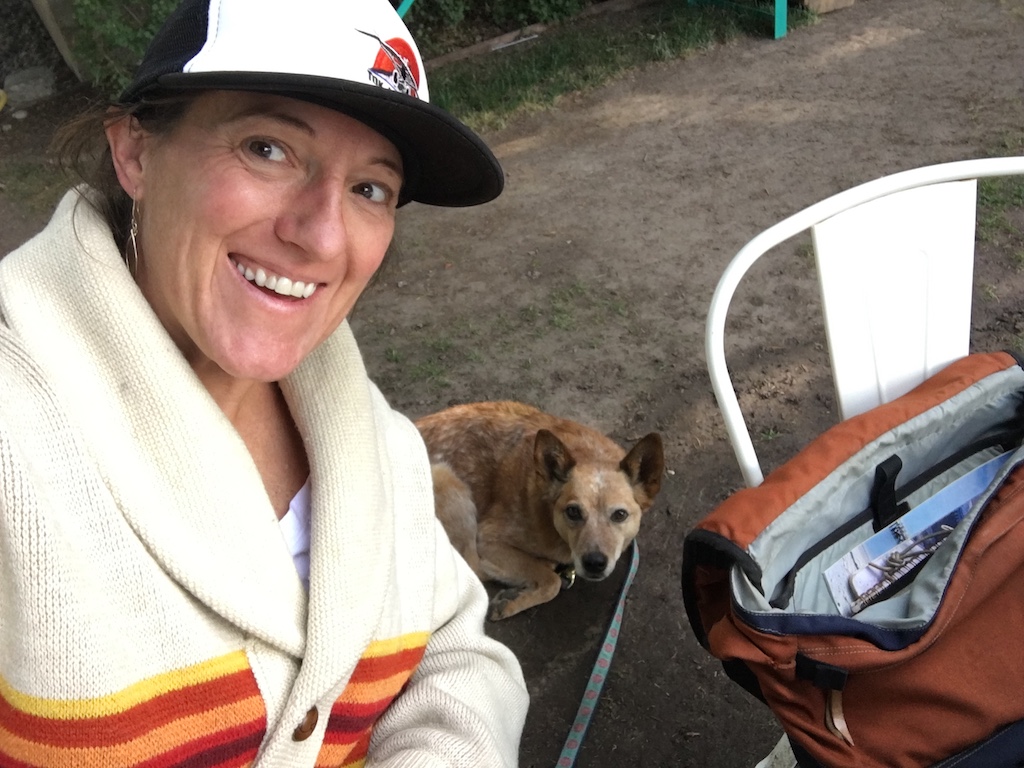

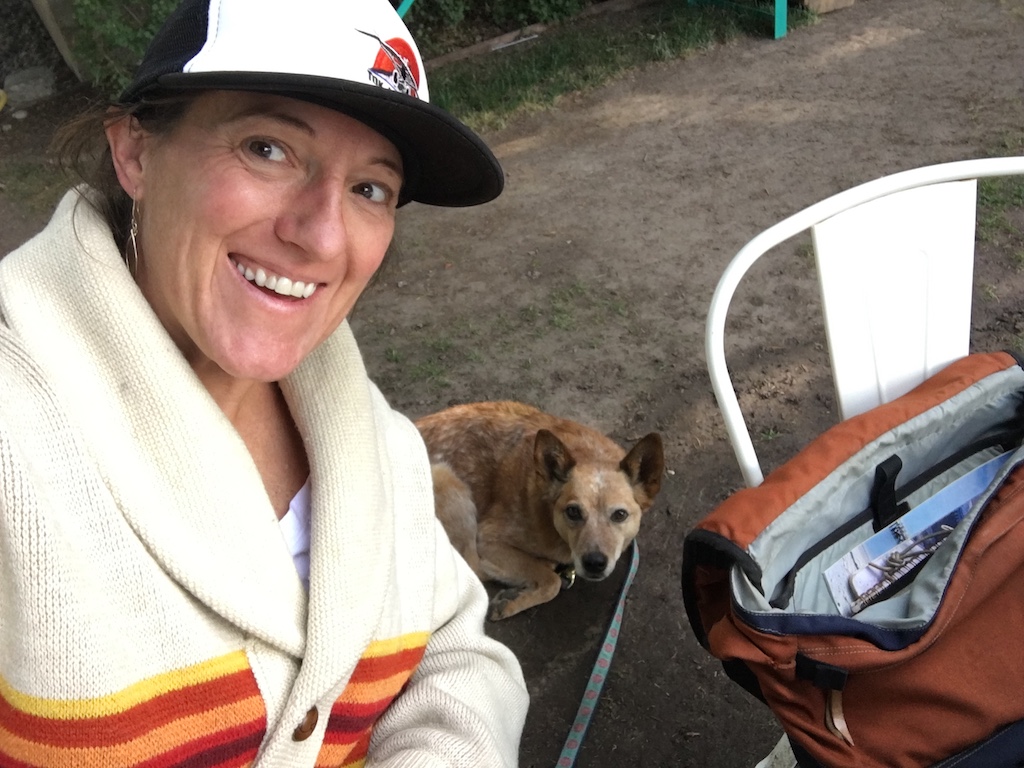

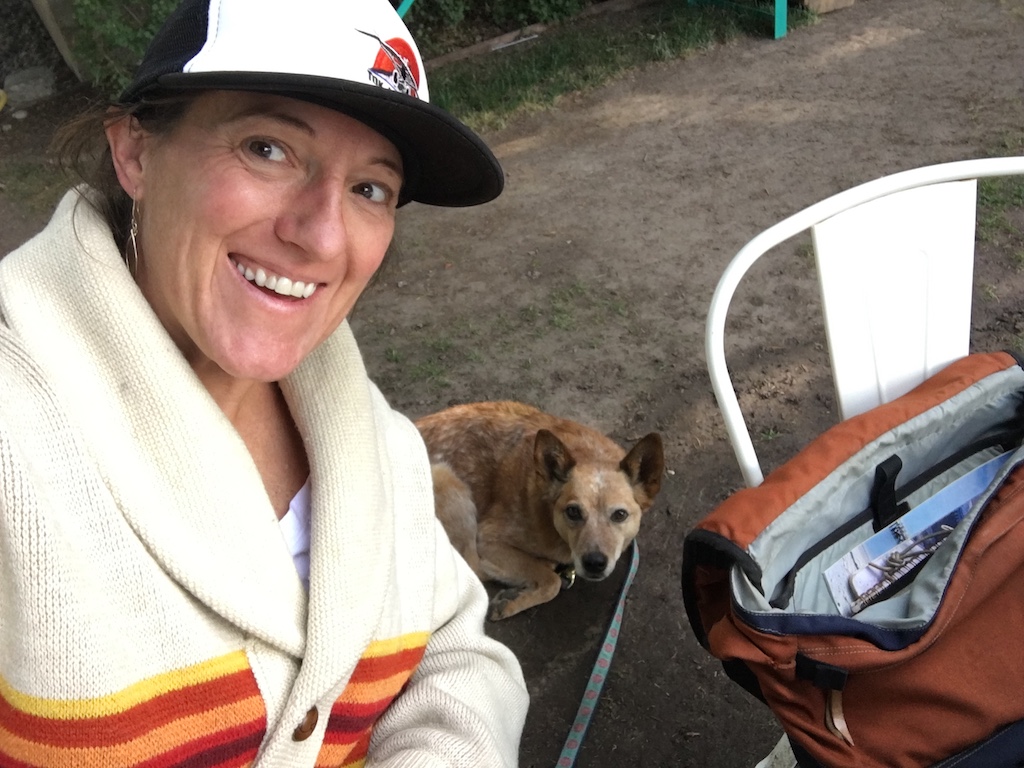

I took a road trip through these parts and found myself in the Basque-American heartland of the West. The route from Boise to Bakersfield showcased the region’s dazzling cultural mosaic as well as majestic landscapes of mountain ranges, big sky basins and desert.

For the epicurean in me, Basque American delicacies like solomo (lamb stew), and the aforementioned (and delicious) picon punch alone made for an unforgettable trip. Lonely desert highways led to tumbleweed-strewn ghost towns, the turquoise lakes of California, and a new outlook on what ‘the West’ really is.

Basques were long time pastoralists in their hilly European homeland, and they found their skills well-suited to the rugged slopes of Idaho.

Boise, one of the largest cities in the Rockies, is directly accessible from most major airports and makes for an ideal starting point for a road trip. Eons ago, glacial activity carved out the dramatic gorges and peaks of the Snake River Valley of southern Idaho, today home to the highest concentration of Basque people in the United States. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, waves of Basque immigrants arrived in Idaho to work as sheepherders in the Sawtooth Mountains, a territory too rugged for cattle but well-suited for ovine grazers. Basques had long been pastoralists in their hilly European homeland, and they found their skills well-suited to the rugged slopes of Idaho.

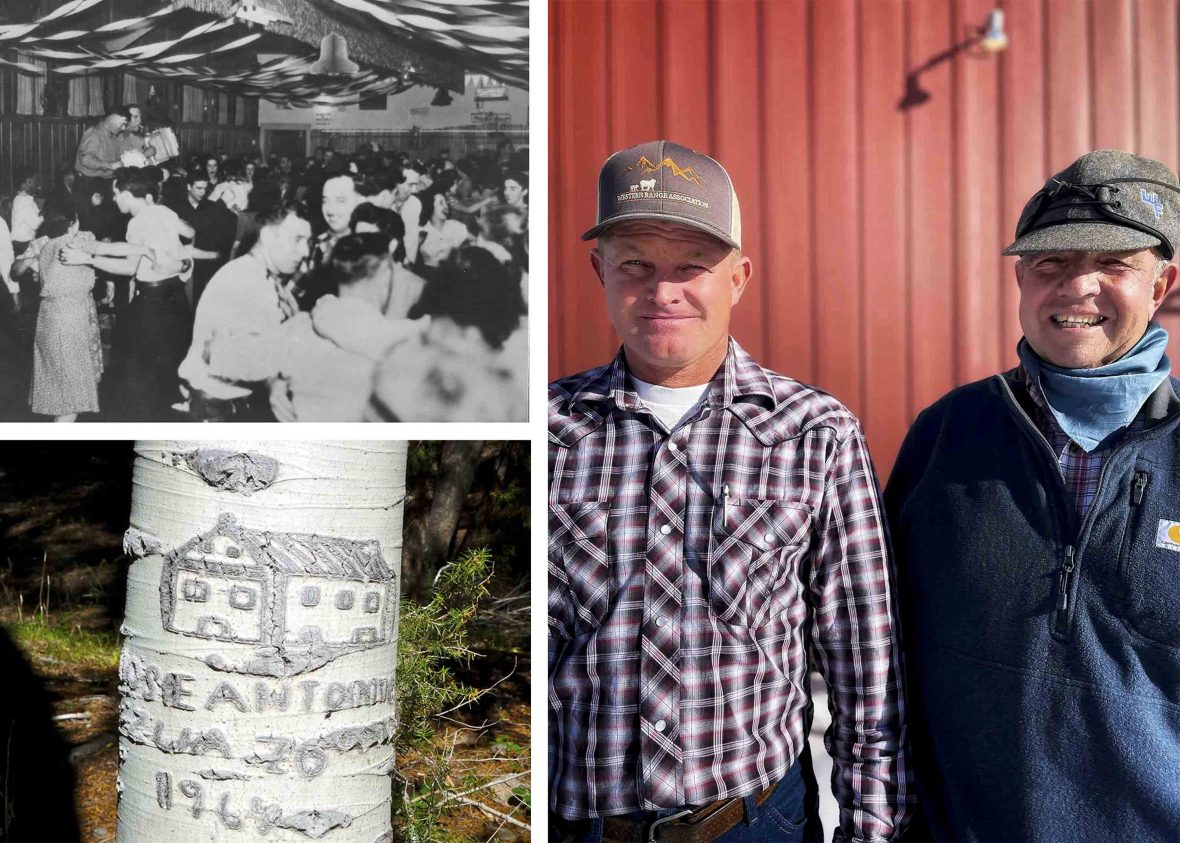

While some émigrés returned to the Basque Country after a few seasons of driving sheep, most ended up staying in southern Idaho, often opening boarding houses and restaurants in towns like Boise, Mountain Home and the to-be ski town of Sun Valley. To pass the lonesome hours on the trail, Basque herders etched ornate designs called arborglyphs into the soft bark of aspen trees. Arborglyphs often depict the lauburu, a cruciform symbol long representative of the Basque people, but just as frequently take a turn for the ribald—portraying nude figures, fantastical animals, or other playful images.

The epicenter of Boise’s Basque culture is the aptly named Basque Block, a neighborhood replete with restaurants, markets and wine shops. Here, I visited the Boise Museum & Cultural Center to take a deep dive into Basque history. The exhibits speak to the contributions of Basque people to both US and world history, and hanging around allowed me to tour a historically-preserved Basque boarding house, or ostatua, from the 19th century. After, while strolling the leafy streets of the Basque Block, I encountered old-timers chatting away in Euskara over cigars, espressos and dominos.

While perusing the block, I found myself sampling a smattering of local delicacies. The Basque Market serves traditional fare like pintxos—tapas-like small plates—charcuterie, and an impressive selection of Spanish wine and sagardoa, non-carbonated apple cider. Ansots, a restaurant recently nominated for a James Beard award, proved to be a delight—incorporating native plants like mountain sage and huckleberry into Basque-inspired dishes. The txacoli, a sparkling wine from the Basque Country, beautifully complemented my plate of manchego cheese and jamón Ibérico shaved directly off a cured pork leg like in Spain.

From Boise, it was about a two-hour drive to northern Nevada, the next leg of my journey. As I drove, Nevada revealed itself—flatter and more arid than Idaho, with the latter’s mountains giving way to sage-brushed blanketed canyons. As in the Sawtooth Mountains, sheepherding was an important industry in the Great Basin, a geological region encompassing Nevada as well as slivers of Utah, Oregon, and Idaho. But in addition to tending flocks, Basques immigrated to Nevada seeking work as gold miners, ranch hands and hoteliers. While Idaho’s Basques came almost entirely from Spain, Nevada’s community originated in roughly equal proportions from Spain and France.

The Basque culinary influence is particularly strong here, often mingled with the flavors of Mexican and cowboy cuisine. Every grocery store I visited in the Great Basin was stocked with vying brands of Basque-style chorizo, sweeter and less spicy than its Mexican counterpart. And in every respectable saloon, hotel bar or casino in northern Nevada there was the notorious picon punch, a potent mix of bitter-orange amaro, lemon and grenadine—the unofficial libation of the state. As Nevadan saloon barkeeps told me, picon punch is distinctively Western, a cocktail created by Basque Americans and only popularized in Europe by repatriates. The story goes that when the FDA banned Picon Amer, a French liqueur containing the slightly toxic calamus root, Basque Americans created a substitution, Torani Amer, that mixed perfectly with grenadine and a spritz of lemon.

Elko, a desert town known for gold mining and the annual Cowboy Poetry Gathering, is home to the Star Hotel. Established in 1910, the boarding house charged Basque herders $1 per day for room and board during weeks away from their flocks. For generations, the Star was the beating heart of Elko’s Basque community—hosting weddings, holiday parties and events. Today, still, diners sit at long tables under a patterned copper ceiling, horse tack and a canopy of Basque flags. The house specialty—baked lamb with bright mint jelly—is the kind of comfort food trail-bound sheepherders must have dreamt about, especially when washed down with red wine or picon punch.

The Martin Hotel is another time-honored Basque boarding house in Winnemucca, a town roughly halfway between Elko and Reno. The “complete entrees” come with a parade of accompaniments like pasta, potato, beans and salad—a meal best shared family-style. Even with a hearty appetite, I ended up sharing these plates with a group of hunters at the hotel’s bar. The group, local guys in their forties, had been in the brush all day hunting sage grouse. The bird’s penchant for roosting in thorny brambles made for an arduous chase, but the reward—succulent and flavorful meat tinged with the flavor of wild sage—was worth the cut hands and tired legs.

This is an American West vast in size and sublime in topography, and as rich and complex as any other part of the country.

From Winnemucca, it’s about two and a half hours to Reno, “the Biggest Little City in the World.” Reno attracts plenty of visitors looking to explore nearby Lake Tahoe or attend Burning Man, but the former cowboy town has no shortage of its own quirks. Traipsing under Reno’s iconic neon lights, I beelined it for Louis’ Basque Corner, a Reno institution for stiff drinks and hearty, lamb-laden dishes.

After crossing the California state line, I found myself driving seven hours through the Central Valley’s orchids, vineyards, and farms—leading me to Bakersfield. Although large-scale immigration began in the 19th century, the Basque presence on California shores stretches back centuries: Andres Urdaneta, a Basque ship captain, bumped into California’s coast in 1565 after sailing east from the Spanish-controlled Philippines.

Much later, the California Gold Rush of 1849 attracted Basque fortune-hunters willing to endure the 6,000-mile journey from the Pyrenees and the subsequent harsh mining work. Around this era, California was just gaining US statehood, and the Basque arrivals to Bakersfield would have found a city with a mixed population of Anglo-American, Mexican and Chinese residents. Today, Bakersfield’s community is mostly of French ancestry, with most early Basque immigrants hailing from Iparralde, the northern region of the European Basque country.

Even though Basque boarding houses I visited across the West claim to have invented picon punch, it turns out that the cocktail likely originated at the Noriega Hotel in Bakersfield. Sitting at the hotel’s long wooden bar—a counter that has served its fair share of cowboys and drifters over the decades—I asked the barman about the origins of this bitter but strangely pleasing libation. Picon liquor, he explained, purportedly boasts a litany of medicinal benefits—from staving off malaria to revving up the libido and enhancing creativity. Torani Amer, the most popular brand of Picon liqueur, is manufactured in California, so it makes sense the cocktail would have originated in Bakersfield.

It’s easy to imagine faraway western states as culturally monolithic. Prior to this road trip, my own conception of the West came largely from two-dimensional Hollywood depictions: John Wayne, Annie Oakley, Billy the Kid, and pioneers in covered wagons defined my ideas about Western history and culture. But as I was driving those long miles between the Rockies and the Great Basin, I began to think a little differently about the American West. It is hard to ignore its vast size and looming topography while humming along under its big sky. But in between rest stops and dinners with strangers, I came to realize that its culture is as rich and complex as any other part of the country. The Basque diaspora is but one thread in this tapestry—a story entwined with those of Native American tribes, Spanish settlements, Chinese and Irish railroad workers, Latin American immigrants, and many others.

Johnny Motley is a Brooklyn-based educator and writer-photographer with bylines on Matador Network, The Points Guy and others. Research and curiosity have taken him to Papua New Guinea, the Amazon Rainforest, and the Silk Road, while Japan and the Himalayas are next on his dream travel list.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: