Bringing about changes won’t be easy.

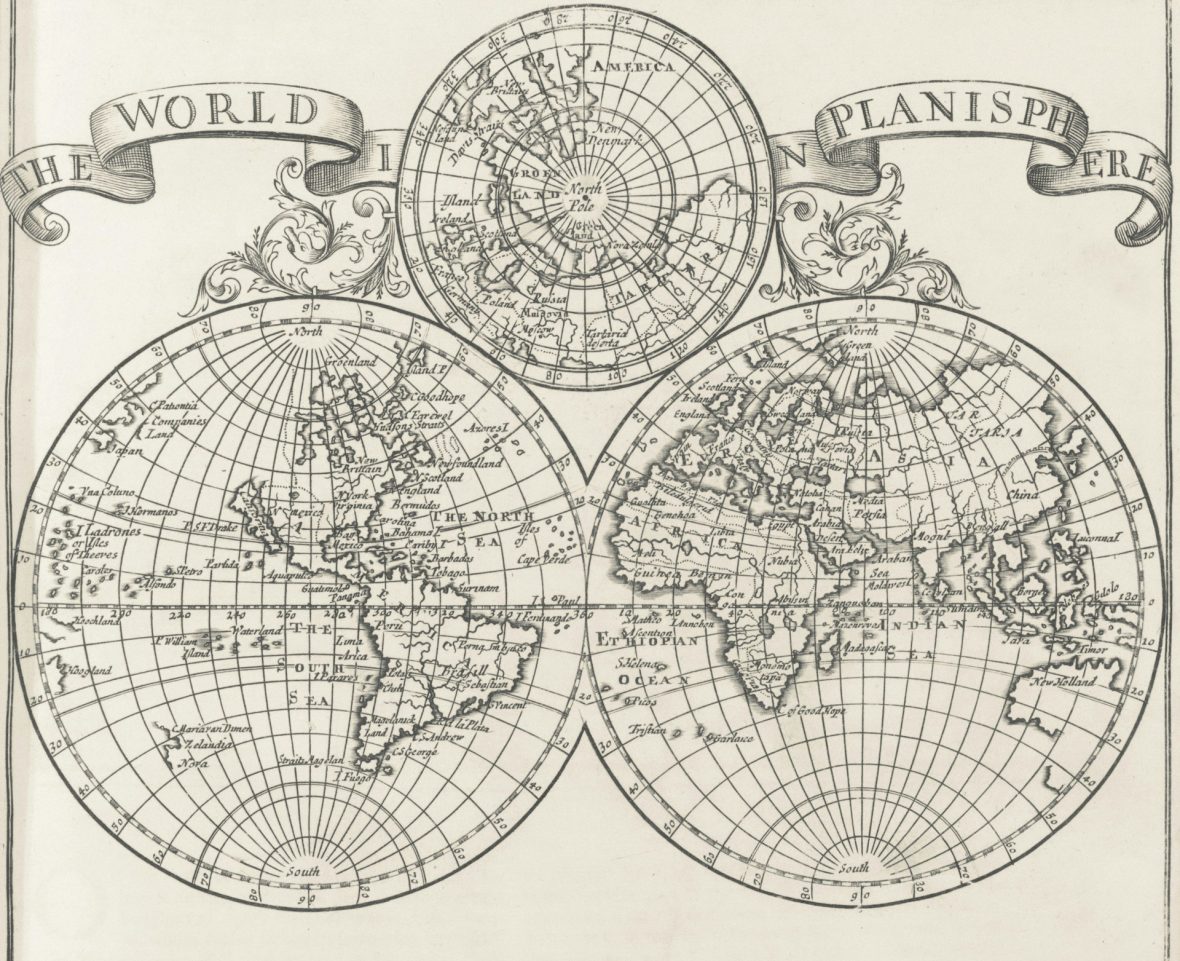

Firstly, global map production is not governed by a single authority. Even if the United Nations were to adopt the Equal Earth projection, world maps could still be drawn in other projections. Cartographers are frequently commissioned to update world maps to reflect changes to names and borders. But the changes don’t always find quick acceptance. For example, cartographers changed English-language world maps after the Czech Republic adopted the name ‘Czechia’ as its English name in 2016. While making the change was not difficult, broader acceptance has been harder to achieve.

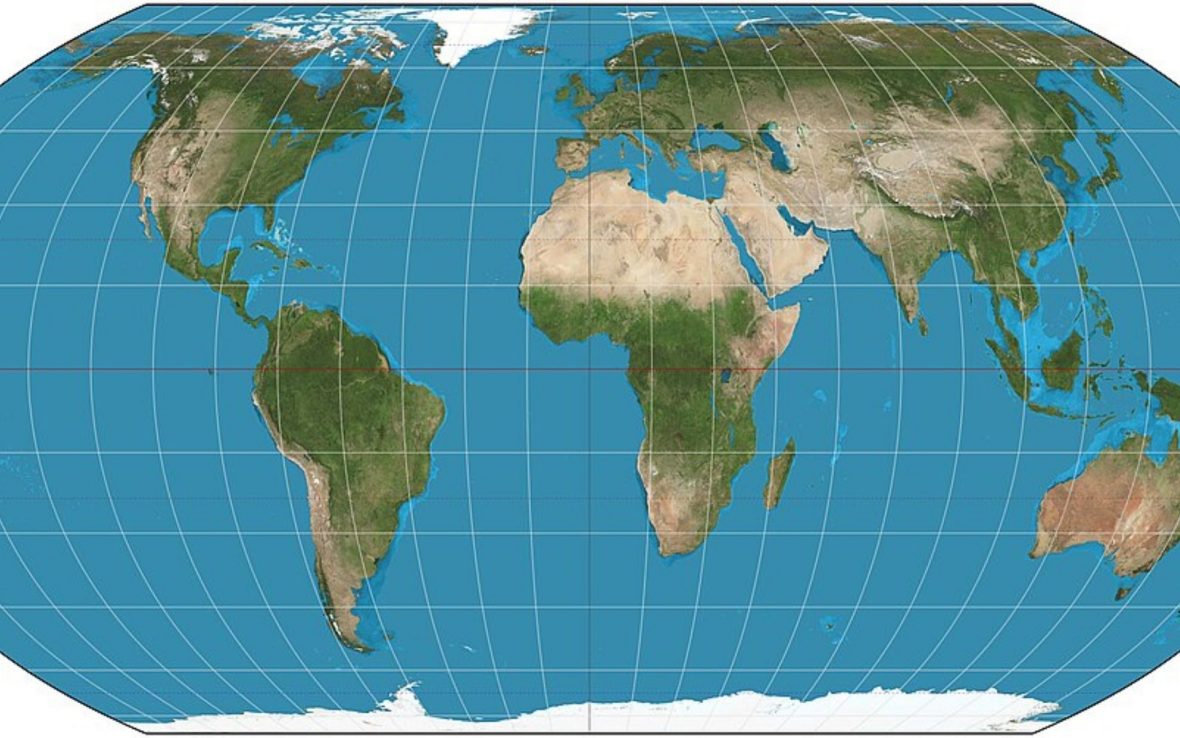

A person’s mental image of the world is solidified at a young age. The effects of a shift to the Equal Earth projection may take years to materialize. Previous efforts to move away from Mercator projection, such as by Boston Public Schools in 2017, upset cartographers and parents alike.

Given the African Union’s larger goals, supporting the Equal Earth projection is the first step in pushing the global community to see the world more fairly and reframing how the world values Africa. Mobilizing social support for the new projection through workshops with educators, diplomatic advocacy, forums with textbook publishers, journalists, and Africa’s corporate partners could help move the world away from the Mercator projection for everyday use.

Shifting to the Equal Earth projection alone will not undo centuries of distorted representations or guarantee more equitable global relations. But it’s a step towards restoring Africa’s rightful visibility on the world stage.![]()

**

Jack Swab, Assistant Professor Department of Geography & Sustainability, University of Tennessee and Derek H. Alderman, Chancellor’s Professor of Geography, University of Tennessee

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.