It’s natural to want to carve your own path when traveling, but sometimes, says our featured contributor Leon McCarron, there’s something special about following in the hallowed footsteps of explorers long gone.

We’re inspired to travel in so many ways. My first desire was to see if the real world matched up to the one I’d read about; my second was to see if I was capable of making my way through either.

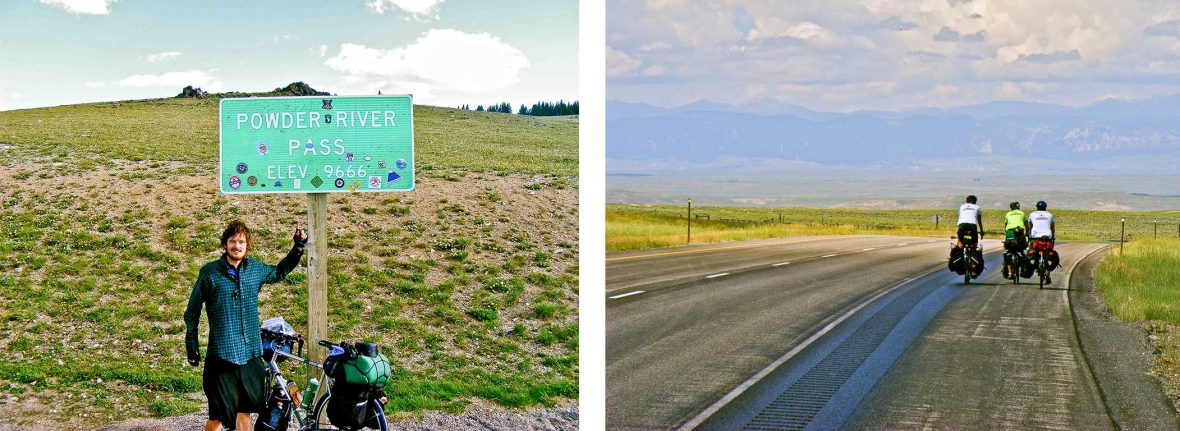

Aged 23, I set off alone on a bicycle in a new continent and, to my delight, discovered places and peoples and ideas that I could never have imagined. The world was not as had been described in my books—it was better.

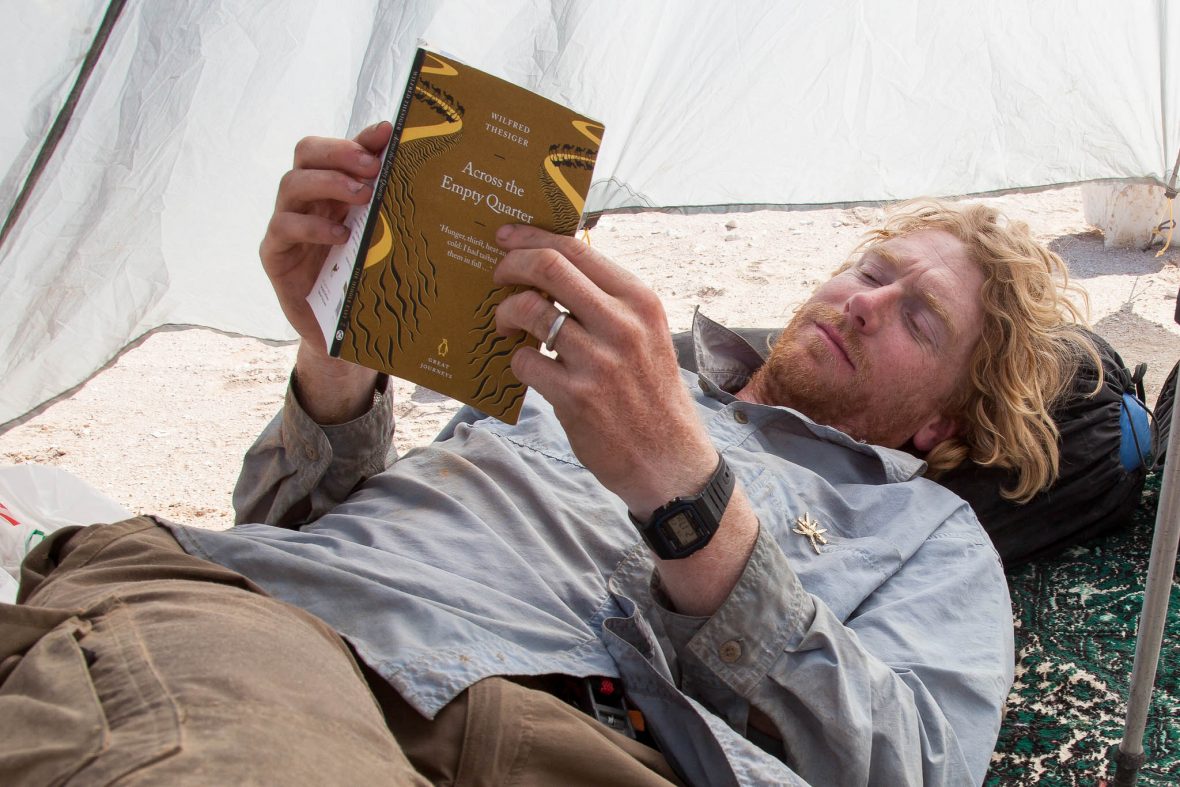

And yet, I’ve always been fascinated by following in the footsteps of someone else—perhaps, initially, it was the appeal of clinging onto the coat-tails of a better, braver explorer, in the hope that some of their wisdom or luck might be transferred onto me.