Nigerian writer Tiléwa Kazeem wants vloggers, bloggers and influencers everywhere to think twice about their next ‘authentic travel’ story.

Nigerian writer Tiléwa Kazeem wants vloggers, bloggers and influencers everywhere to think twice about their next ‘authentic travel’ story.

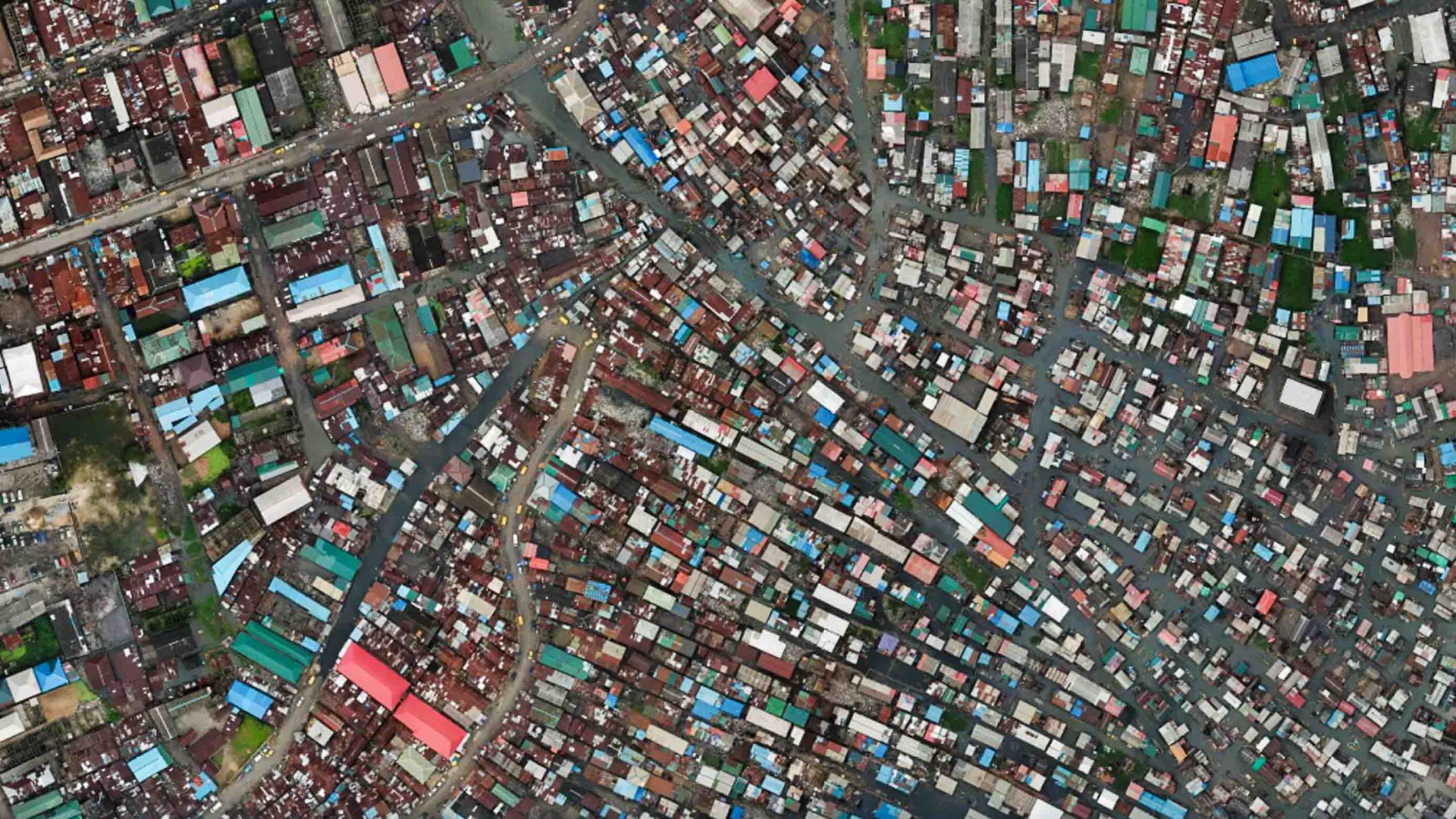

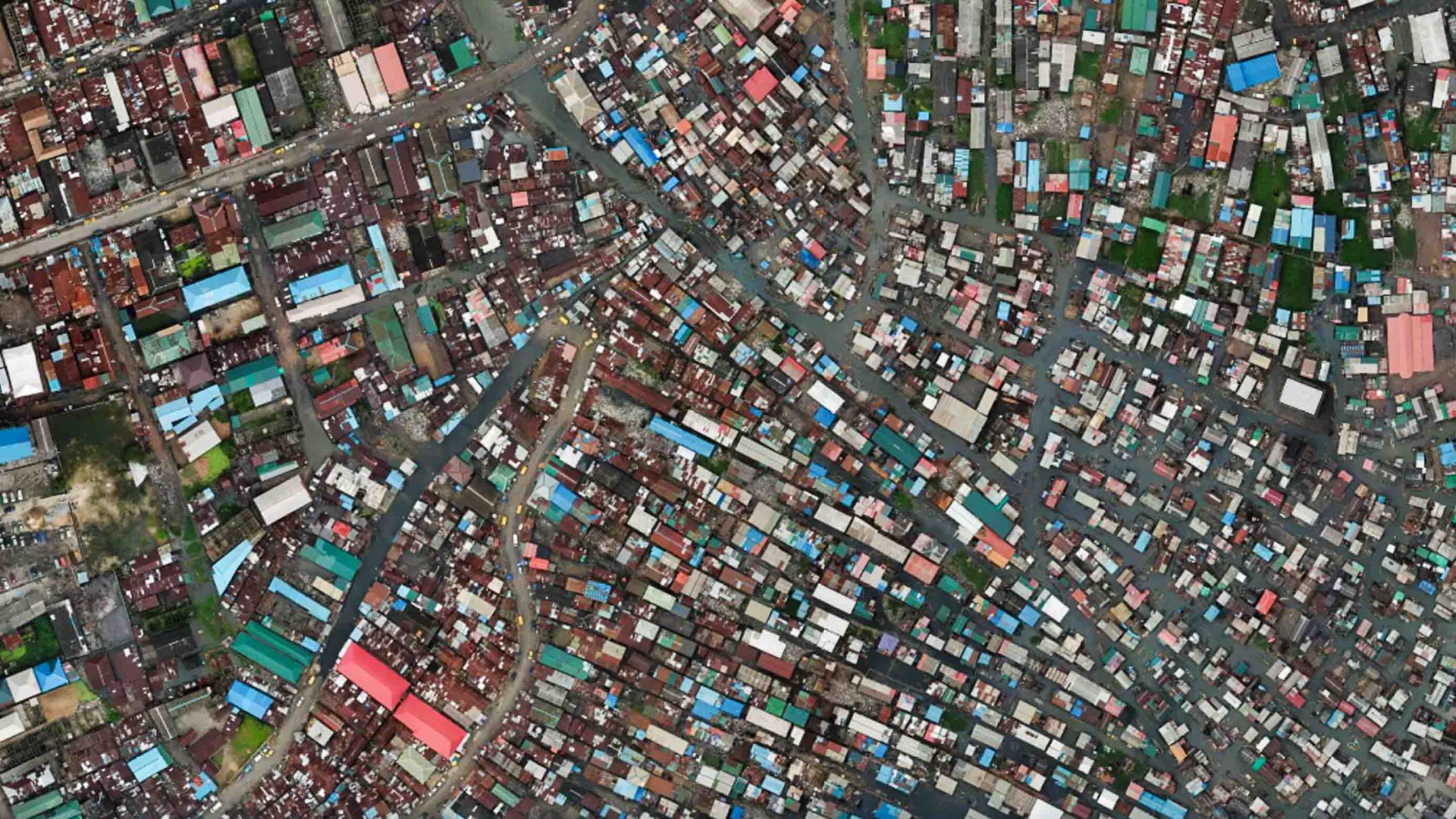

“There are people that canoe through the Makoko waterways, videoing withering octogenarians for content. We don’t need that,” says Rosemary, a provisions seller in Makoko, the informal fishing community in Lagos, Nigeria and ‘world’s largest floating slum’. Rosemary’s words reflect a growing local discontent as vloggers and bloggers flock to the town seeking to capture ‘authentic poverty’.

What they often miss is the vibrancy of life here, and the dignity and resilience of those who call Makoko home. Instead, the community is reduced to poverty porn—a voyeuristic portrayal of hardship—key ingredients being dirty waterways and houses made of scrap planks—designed to evoke pity and gain views.

In a world obsessed with viral content, the people of Makoko are being objectified, and their stories oversimplified. In reality, Makoko is home to a school, a hospital, motels, people who fish, people who smoke the fish, and people who sell the fish on mainland. It’s a village ecosystem that works.

As a Nigerian, I roll my eyes at every video made about Makoko that pops up on my YouTube feed—and it feels like there’s a new one every day. But what really pushed me to visit for myself, and advocate on behalf of the town, was seeing a Youtube Short of a Mokoko woman in a canoe, desperately trying to hide her face from the camera. It was intrusive and incredibly disrespectful on the part of the cameraman.

It made me ask myself: Since when did a lower socio-economic community become a tourist attraction? Renting a canoe to film people in their homes feels like trespassing. And it’s unnecessary when Lagos has real tourist spots—museums, beaches, historic sites—that are worth visiting. Or if you just want to see a floating village, Benin’s Ganvie, probably the largest lake village in Africa, is an actual destination. Although it’s no Venice, with fewer gondolas and more hazards.

To those who really want to visit Makoko, make sure your intentions are genuine. Are you here to help or to exploit?

Established in the early 19th century, the Makoko stilted community gained prominence when fisherfolk from Benin, Togo, and Ghana began emigrating in search of good fishing grounds. Migrants from other parts of Nigeria soon followed, drawn to the burgeoning city of Lagos.

What stands today is a population estimated by locals to be about one million (although it’s difficult to know, given the village was not recorded in the 2006 census) and a blend of cultures: The Eegun people, who migrated from the inland waterways of Badagry and the Benin Republic; the Ilaje people, originally from Ondo; and the Awori people, the original settlers of Lagos. The languages spoken on the waterways are French, Yoruba and Egun, a local dialect.

To get to the ‘Venice of Africa’, I choose to take the less scenic route through Apollo, one of the six communities that make up wider Makoko. My tricycle driver, who has made this trip countless times, enquires about my intentions and asks if I have a contact waiting for me—if he can spot me as a visitor, so can everyone else. It’s not my appearance that matters though—anyone visiting Makoko needs a guide, for both access and safety.

Luckily, I have one saved in my phone—Augustine Omogbemi, a stocky man in his early 30s and Makoko’s ‘King of the Boys’. Born and raised by the waterside, Augustine serves as a youth leader within the informal community system. Part of his role, besides guiding visitors like me, is doing his best to ensure peace in the village, prioritizing the people’s interests above his own.

“Recently, an artist came to the waterside to shoot a music video, and before he left, he donated to the community,” he tells me. “I did my best to make sure everyone got a little something, no matter how small.”

Since his appointment earlier this year, transparency has been Augustine’s guiding principle. He explained that while most people in the community are content, things can be tough, and the village has had an issue with well-meaning donations—from NGOs and visiting individuals—going missing. Sometimes pocketed by families in need, other times donors have been harassed or had their contributions taken by thugs manning the entrance to the town.

Disheartening events like this is exactly what prompted the need for a new youth leader—big shoes that Augustine is trying his best to fill.

As we move through the town, smoke billows from its shanties, evidence of one of Makoko’s main trades: Smoked fish. This trade, alongside sand dredging and salt making, sustains many residents, like Sam, a 46-year-old father and fisherman.

Sam took over his father’s fishing business and has lived on the lagoon since he was born. “Fishing raised me, and it’s how I’ve raised my family,” he tells me. The fish Sam catches is then smoked and goes on to end up in the vegetable soup and tomato stew that is eaten all over Nigeria.

Yet vloggers, bloggers and ignorant tourists continue to reduce Makoko to a backdrop of misery, magnifying its hardships while ignoring real contribution from the settlement. The issue isn’t a lack of knowledge, but a refusal to look deeper. To those who really want to visit Makoko, make sure your intentions are genuine. Are you here to help or to exploit?

Feeling the camera’s gaze, I realize how easily roles can be reversed. I’m no longer just an observer; I’m now the subject of someone else’s detached curiosity.

Makokorians have enough challenges to contend with without having to worry about going viral on YouTube. Just recently, Lagos State issued a notice for villagers to vacate, stating they’re at risk to the power lines that run across the ocean. This has been an ongoing issue between the community and State government dating back to 2012 when the first demolition order came with a 72-hour evacuation notice.

Police and soldiers entered Makoko to remove the community and destroy homes, but a community leader, Timothy Hunpoyanwha, was shot dead by police in the process and evacuation plans were paused. Since then, the community has received ongoing threats of eviction.

As Augustine and I wrap up our chat, I notice one of his attachés wielding their phone oddly, the camera aimed directly at me. I had been explicitly instructed not to record while in Makoko, and so this feels like an invasion of my privacy. And, just for a moment, I understand what it’s like to be a spectacle. I realize how easily roles can be reversed. I’m no longer just an observer; I’m now the subject of someone else’s detached curiosity.

This experience highlights that it’s not just the lens that shapes the story, but who wields it and their intent. The real question isn’t whether to record, but what stories we choose to tell and how they’ll impact those who live them. Are our stories being told with empathy and compassion for Makoko’s unique culture and history or are they perpetuating stereotypes and exploiting a floating Nigerian village for gain?

Until then, just stop vlogging about Makoko.

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Freelance writer, journalist, and culture enthusiast, Tiléwa Kazeem transcends niche boundaries in identity, tech, relationships and travel, championing the voices of the underrepresented. When not immersed in writing or culture, he enjoys watching or playing football and finds contentment in moments of stillness.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: