Applying for a tourist visa can be a pain. But the citizens of Uzbekistan need a visa to leave. The result? A huge domestic tourism market. Central Asia travel expert Caroline Eden joins the locals as they go adventuring in their homeland.

Next time you groan while filling in a tourist visa form, spare a thought for the citizens of Uzbekistan. While many countries demand a visa for tourists to enter, a handful of countries ask their nationals to apply for a visa in order to leave. Uzbekistan is one such country.

Cuba, by comparison, scrapped its exit visas in 2013. But along with Saudi Arabia and North Korea, Uzbek citizens—for now—still need to apply for an exit visa to go to a country outside the Commonwealth of Independent States (a large swathe of the former Soviet Union) and sometimes Tajikistan and Turkmenistan, depending on the political climate.

The long journey, around six to seven hours, to Bukhara is well worth it, though. A city known for its rugs and its ruthless emirs (the Muslim, mainly Arab, rulers such as Nasrullah who beheaded his Italian watchmaker in a fit of rage when his clock stopped), Bukhara is the gem in Uzbekistan’s tourism crown with its historic madrassas, textile shops and chaikhanas (tea houses). During Persian New Year, celebrations fill the streets.

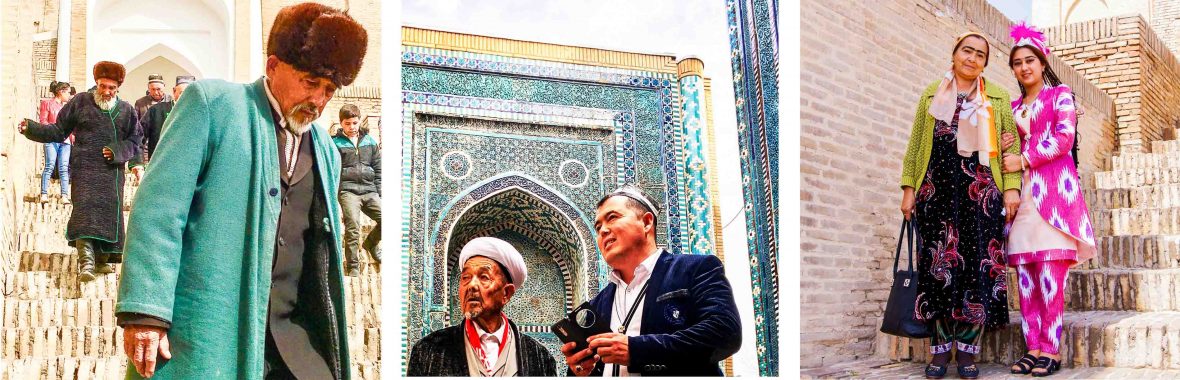

I met these ladies in their finest clothes at the Lyab-i-Hauz, a plaza and pool in the old town.

“Where are you from?” I asked.

“Kasri Orifon, six miles away. You may know it? It’s where Bahauddin Naqshband, the great Sufi saint, is buried. Come and visit us! Come for tea!” they shouted as I took their photo.

The little village of Kasri Orifon is dominated by the Naqshbandi Mausoleum where Uzbek pilgrims, from all over the country, arrive to visit the tombs and mosques and pray to Naqshbandi, the founder of the Sufi Order.

RELATED: Inside the lives of Mongolia’s nomads

There are always a few men hovering around a large tree trunk, too, that appears like a piece of drift wood. I asked my local friend Rimma what the men were doing. “They are breaking off tiny pieces of wood to be kept as a souvenir,” she told me. “They believe this tree sprouted from Naqshbandi’s walking stick. They’ll put the little pieces into amulets.”

We questioned the ethics of this behavior then concluded that, given Naqshbandi is the patron saint of craftsmen (he was the son of a weaver), maybe he’d look lightly on this creative hustle.

Of the three cities that most tourists visit—Khiva, Bukhara and Samarkand—the latter is Uzbekistan’s ‘heavy hitter.’ Samarkand has the Registan, a dizzying ensemble of three madrassas, a giant plaza, and the Gur-i-Emir, the mausoleum of Turco-Mongol king Timur who also goes by the name of Tamerlane, who commissioned many of this city’s great structures.

For me, it is the Shah-i-Zinda, a series of turquoise-tiled mortuary chapels, that’s the most exquisite sight in all of Central Asia. English travel writer and adventurer Rosita Forbes, writing in the 1930s, described their bluish hues looking as if they were “ … steeped in sea-water. All incomparable mosaics of this deep, quiet pool of colour contrasted or blended with the rich browns and golds of the earthen walls. Sea and sand with sunshine caught between them.”