It’s not top of the list when it comes to city breaks, but Leon McCarron was surprised—and heartened—when he visited Baghdad, a city that once upon a time was the center of the world.

“We’re going to one of the most interesting places here,” says my guide Mustafa as he drives through the streets in his silver Mini-inspired car. “You’ll see what this city is really like when we get there.”

We park up outside an old mosque with fading blue turquoise tiling and an ornate stone doorway, then walk along a broad boulevard of busy stores, people spilling out onto the road. Behind a man selling sugarcane from a wooden cart is an arched entrance to a smaller, narrower street that’s fully pedestrianized—or perhaps so busy that no vehicles dare enter.

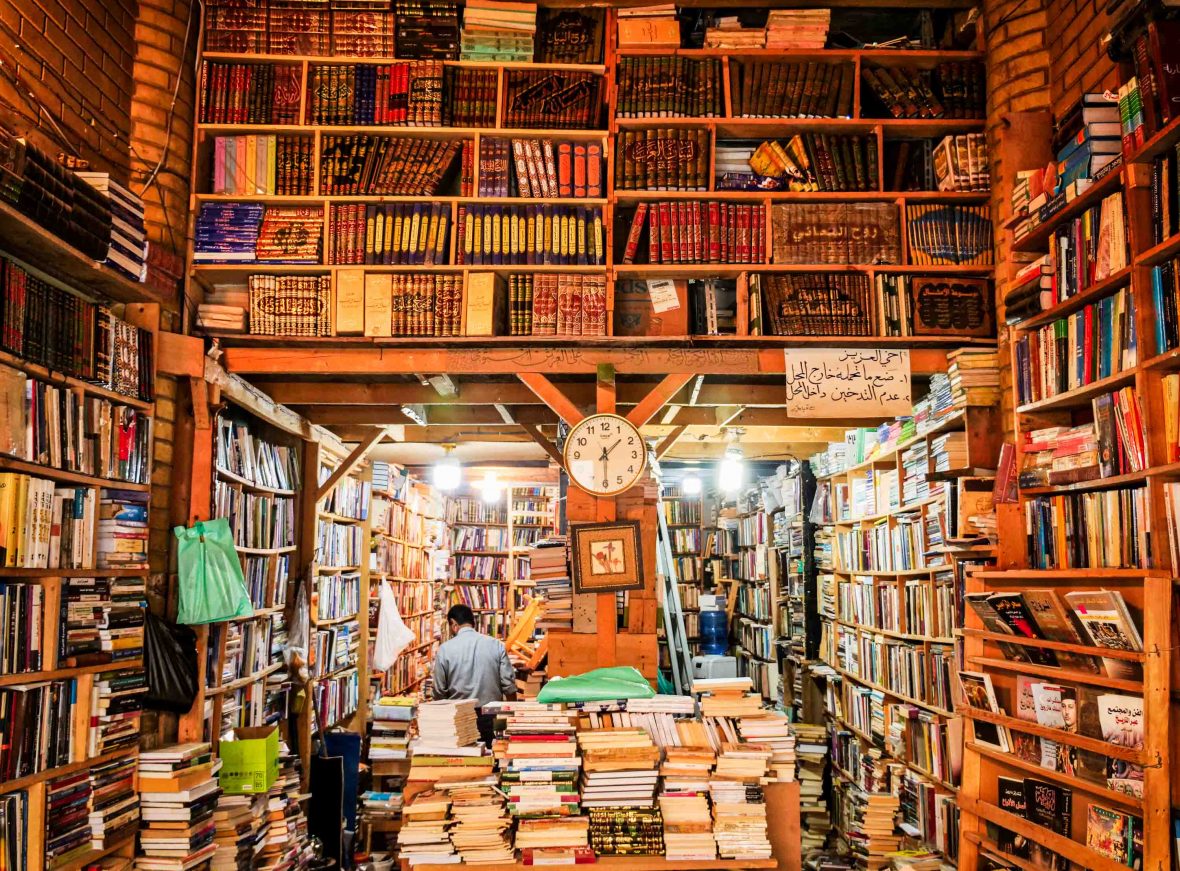

“Welcome to Al-Mutanabbi Street!” said Mustafa. We’ve arrived in the middle of the weekly book market—Mustafa promises this will say “more about the city today than any news report.”

Even with an open mind, this was not the scene I had expected on my first visit to Baghdad.