The rebellious, scandalous, dangerous, and dirtbag-y history of climbing will forever be remembered, thanks to Ken Yager, a conservationist and climber, who has worked tirelessly to preserve it.

The rebellious, scandalous, dangerous, and dirtbag-y history of climbing will forever be remembered, thanks to Ken Yager, a conservationist and climber, who has worked tirelessly to preserve it.

On a family trip to Yosemite Valley aged 13 years old, Ken Yager fell in love.

“I was so infatuated with the place, it was like a magic kingdom to me,” Yager reminisces while sitting by a creek in his “Send Your Face” Grateful Dead t-shirt and shorts. “The first time I touched the base of El Capitan, I looked up at the rock and said out loud, ‘God, I gotta climb this thing.’”

Like a first love, Yager said Yosemite was all he could think of through junior high and high school. He made plans to move to the Valley after graduation.

“At 17 years old, my father dropped me in Camp 4 with all my climbing gear, some hiking gear and a little bit of food and money so I could pursue my dream of climbing,” Yager smiles. “My mom was worried.”

It was a revolutionary time for America, with that grand feeling of rebellion. Yosemite had big walls to climb and a free place to live—aptly called Sunnyside Walk-in Campground. It was known as such because it was on the sunny side of the Valley. Today, it’s called Camp 4. The modern heroes (and grandfathers) of climbing—like the late Warren Harding, Tom Frost and Royal Robbins—were putting up bold first ascents and making headlines. The climbing life looked appealing.

However, to remain in the Valley and pursue a passion for climbing the titanic granite walls as a cash-poor climber, that meant laying low around the authorities and dodging rangers. The personality clashes are well-documented in the movie, Valley Uprising: Yosemite’s Rock Climbing Revolution, but the bottom line is this: Climbers had a reputation for being troublemakers, especially because there were often drugs involved.

These same climbers, though, were important for technical search-and-rescue missions in the park as they were more skilled than rangers at getting to precarious spots.

According to Yager, one of the craziest stories from those colorful days in Yosemite is when a plane crashed in the Lower Merced Pass Lake. After authorities did what they could to secure the scene during the winter, climbers moved in on the cargo, which happened to be dope. Selling weed soaked in jet fuel was as sketchy as it sounds.

When Yager ruffled the feathers of the park service with enough trivial misdemeanors to warrant trouble he didn’t want, he dwelled in a cave for almost two years.

“It was probably the best place I ever lived! It was really easy to take care of. I didn’t have to mow the lawn or mop,” Yager says.

As the cat-and-mouse games between rangers and climbers continued through the 1990s, Yager simultaneously built up his climbing resume. He humbly reveals he climbed El Capitan not just once like he originally wished as a youth, but about 60 times using multiple routes. More importantly, he started to stay out of the kerfuffle and change his tune to focus on preservation.

“I couldn’t live off of canned food forever,” Yager admits. That’s when he started working as a Yosemite Mountain School guide to use his hobby to make a living.

“It was really embarrassing when I’d explain to people how to leave no trace and behave in the woods. I’d talk about what a beautiful and wild place Yosemite was. But watch out! You’re going to step in some toilet paper.”

While tiptoeing over piles of garbage, Yager became increasingly frustrated, and eventually had an epiphany.

“I could be angry for the rest of my life, or I could do something positive and change it around.”

In 2004, he started the annual Yosemite Facelift. Now entering its 17th year, the five-day clean-up event takes place every September. Over the years, Facelift volunteers have collected more than a million pounds of trash from Yosemite.

“I wanted to show that climbers are a little more responsible and a little more involved than we get credit for,” Yager says. “I feel it’s important for us to take care of those areas, not only as a PR thing, but also to show that we’re a serious user group and a useful user group, and one that land managers should work with.”

Yager’s other intention—besides the basic goal of cleaning up toilet paper—was to make the climbing community a steward of the park and give climbers a seat at the table.

“Doing Facelift helps us ensure that there’s a future climbing history,” Yager emphasizes.

But just as much as wants to ensure a future, he also wants to preserve the past.

In the early 1990s, Yager and a fellow Yosemite climber, Mike Corbett, started gathering climbing artifacts—everything from journals to equipment from the 1940s big-wall climbing pioneer, John Salathé. Their assortment quickly grew into the thousands, filling up Yager’s spare bedroom. They realized the significance of what they were building when it served as key evidence to get Camp 4 placed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Yager and Corbett had conversations about establishing a permanent museum to immortalize the historical collection and share it with the public. They started gaining some traction in a variety of ways, by securing grants to catalog everything and displaying temporary exhibits, like one at Autry Museum of the American West in Los Angeles in the 1990s.

“There’s a lot of big collections out there,” Yager explains. “But this—at least for Yosemite—there’s nothing that’s even close to this.”

When you compare some of the gear early luminaries used—like Salathé’s hand-forged hook and heavy haul bags—it’s not surprising to see how the climbing time on El Capitan went from 27 hours to two hours.

Even after Corbett left the Valley in the late ‘90s, Yager kept up the lot, cold-calling families of past climbing heroes for memorabilia. People trusted Yager to keep these priceless treasures alive.

From the spike used by George Anderson during his first climb of Half Dome in 1875 to the pitons forged out of stove legs used on the first ascent of El Capitan in 1958, it’s all there.

He also continued the dream of having a permanent fixture within the Valley Visitor Center in the national park. In 2003, Yager established the non-profit Yosemite Climbing Association to pursue the mission to preserve and protect climbing history and make it available to the public.

“When people heard what I was doing, they’d say, ‘Oh great idea, but that will never happen,’” Yager laughs. Even though climbing has always been an incredibly important thread in Yosemite’s texture, anything involving government approvals has many hoops to jump through.

“I can’t remember NOT hearing from Ken about a museum in Yosemite,” says Phil Powers, former chief executive officer of the American Alpine Club. “But Yosemite may be the single most iconic place for climbers in the world. There is no better place to help non-climbers understand what we do and why we do it.”

After delays due to the pandemic, his dream came true. The Yosemite Climbing Association officially opened its climbing museum and gallery last year. It sits at the intersection of Highways 140 and 49 in Mariposa, California, a town outside of Yosemite.

By the time the doors opened, Yager’s collection had grown to about 10,000 pieces, so it was easy to fill the space. Today, the Mariposa museum offers a chronological display of real artifacts and photographs charting the evolution of rock climbing in Yosemite from 1875 to the present day, capturing notable moments and preserving them.

From the spike used by George Anderson during his first climb of Half Dome in 1875 to the pitons forged out of stove legs used on the first ascent of El Capitan in 1958, it’s all there… Lynn Hill’s shoes from her free climb of the Nose. The cell phone Tommy Caldwell dropped during his first ascent of El Capitan’s Dawn Wall in 2015. The gear spans decades and demonstrates just how rock climbing went from a fringe activity to a full-on culture and Olympic sport.

Yager says it’s hard for him to nail down his favorite piece. “I’ve got a pretty good Alex [Honnold] exhibit,” Yager says. “I have a blank case with plexiglass over it dedicated to Alex’s Freerider gear… which means it will sit empty.” (For the record, Alex free solo-ed this route on El Cap in 2017, so there’s no gear to display).

The Mariposa location is open year-round, seven days a week, and has one paid employee—although it’s mostly run by volunteers. There’s a suggested donation of $5 as the entrance fee, and Yager is still soliciting benefactors and donors to keep the museum operational.

Inside Yosemite’s boundaries, another exhibit opened in the Valley Visitor Center this year, thanks to a partnership between the National Park Service, American Alpine Club and Yosemite Conservancy. About 600 square feet is dedicated to a broader view of climbing with hands-on climbing gear for visitors to try out, like a rock wall with finger cracks and buckets of weird-looking mechanical devices.

“Over 4 million people a year come to Yosemite National Park. One of the most popular things for people to do and for visitors to learn about is rock climbing,” says Scott Gediman, Yosemite’s chief public affairs officer of media and external relations. He calls the exhibit “a heartening evolution” between the National Park Service and the climbing community, moving from animosity to a shared partnership in park preservation.

Corbett died in May of 2022, but said he was elated to see both physical locations. “He was the happiest he’s ever been,” Yager says.

From 1875 to present day, Yager has seen climbing history set into stone. And, through his continuing efforts, he’s a part of it. He won the David R. Brower Conservation Award from the American Alpine Club for his conservation and preservation of mountain regions and has been inducted into the Hall of Mountaineering Excellence.

Uniting rangers and climbers and proving how Yosemite is truly the birthplace of American rock climbing is quite a turnaround from those early days. And no one but a homeless dirtbag climber living in a cave could’ve made it possible.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us any time at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response.

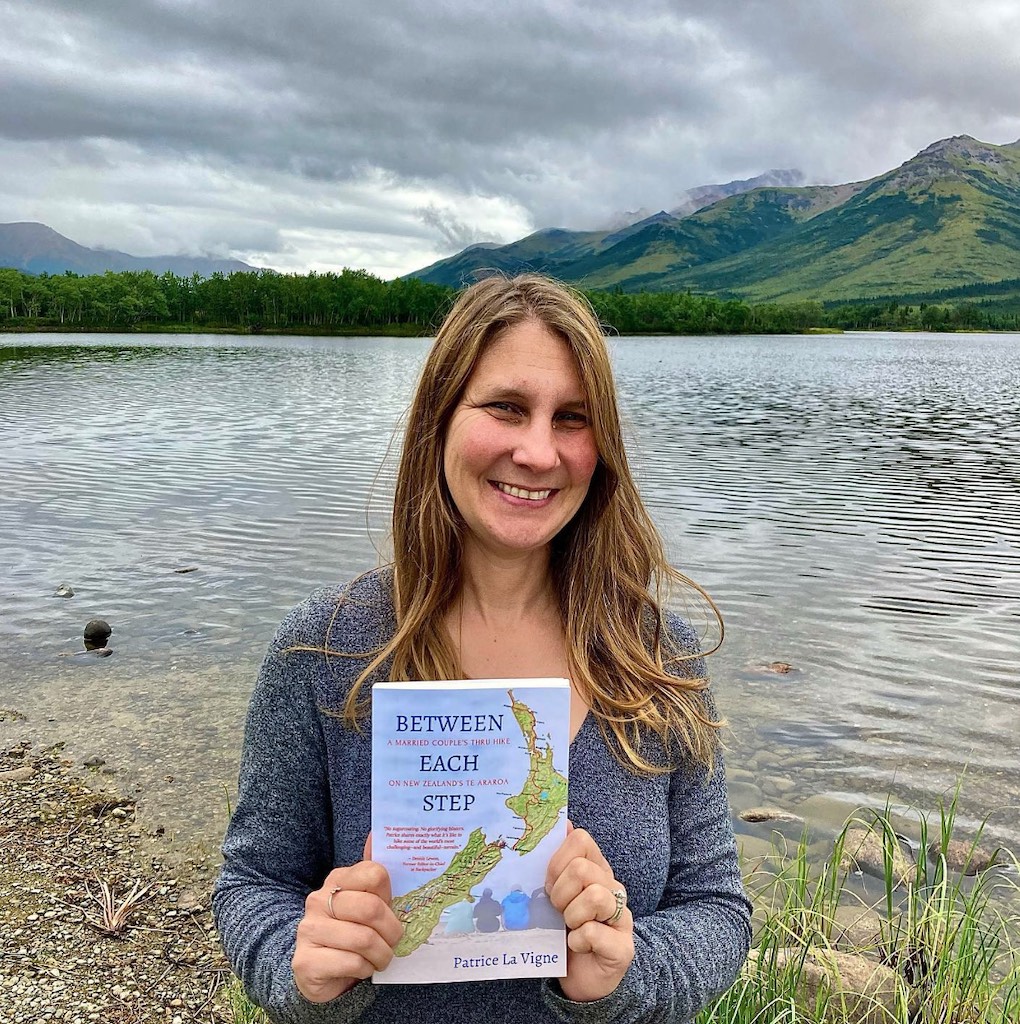

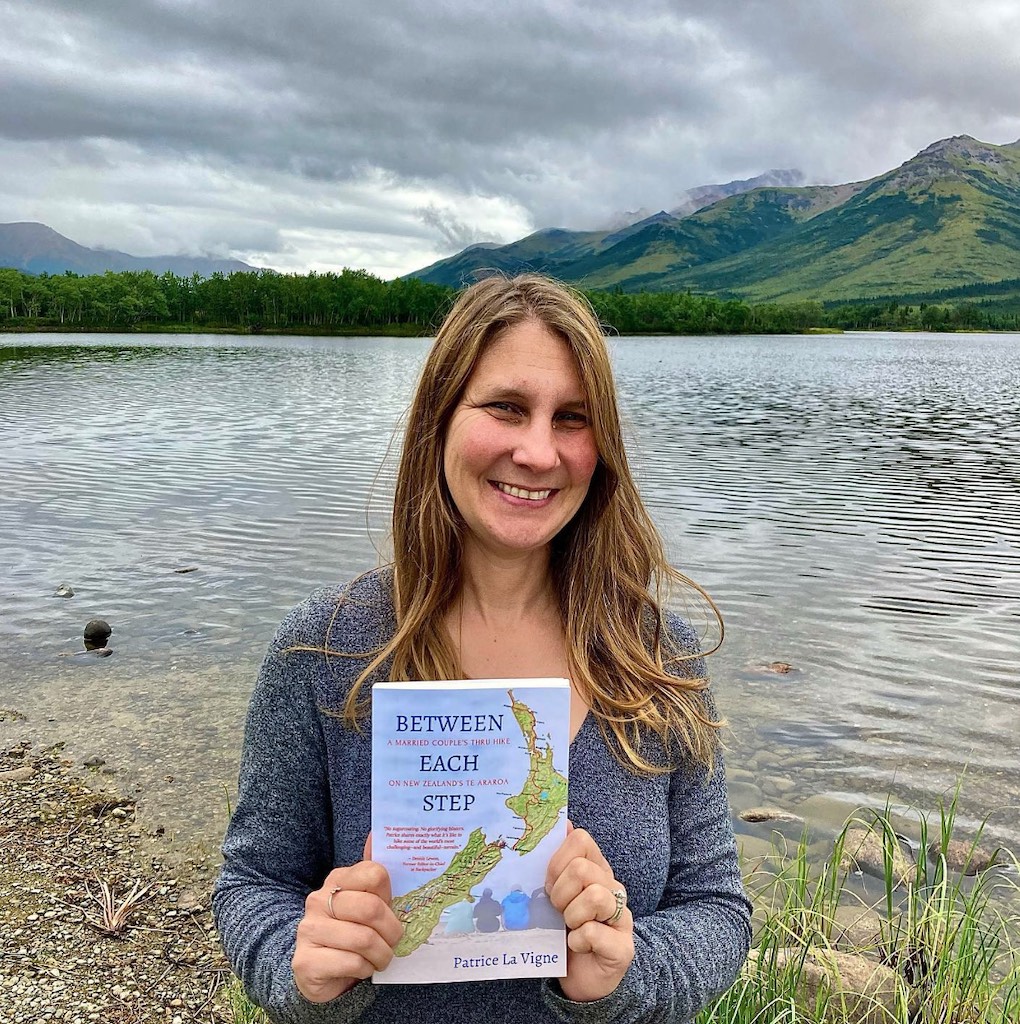

Patrice La Vigne is a freelance writer and author of 'Between Each Step'. Her bylines include Backpacker, Outside, Outdoor Business Journal, GearJunkie and Alaska Magazine. Though she lives in Alaska, she’s backpacked more than 6,000 miles on trails around the world and has road-tripped across America at least 40 times.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: