While overtourism protests take place in parts of Europe, Greenlanders are creating a new form of tourism, one based on so-called ‘authentic intelligence’. But what does it all mean?

While overtourism protests take place in parts of Europe, Greenlanders are creating a new form of tourism, one based on so-called ‘authentic intelligence’. But what does it all mean?

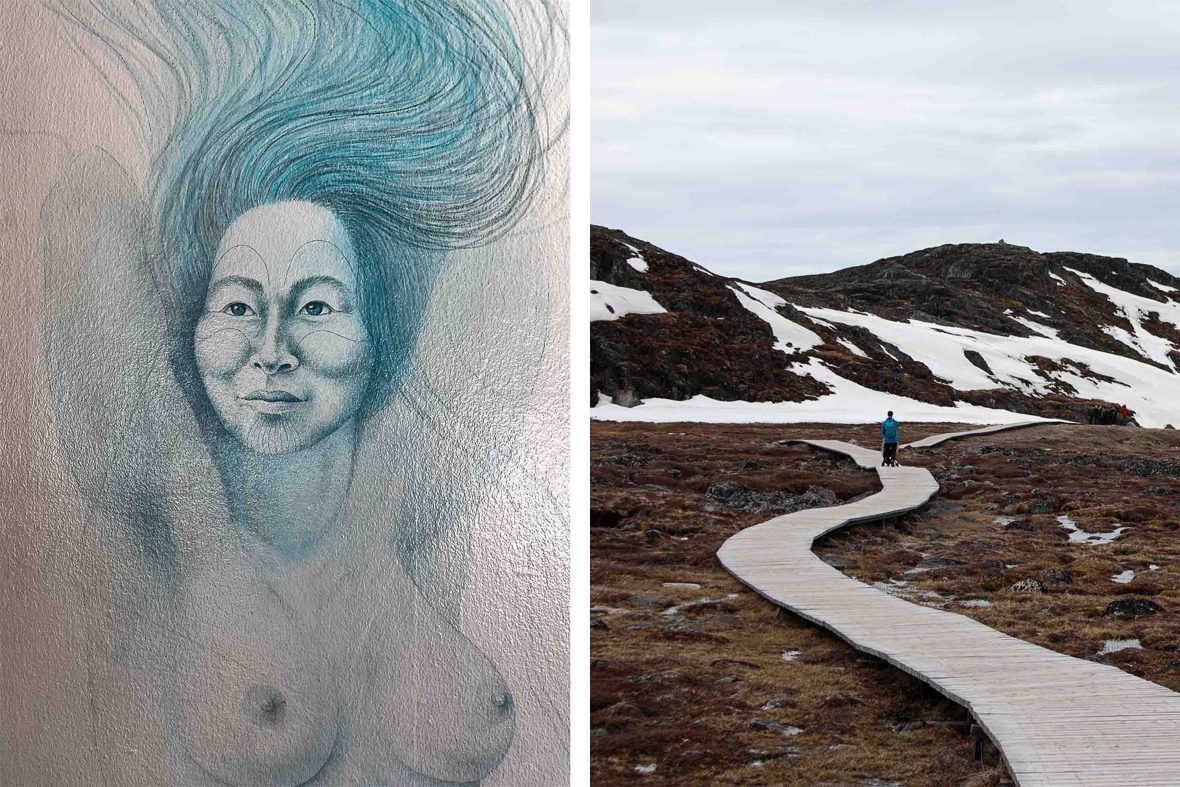

Her name is Sassuma Arnaa and she’s known as the Mother of the Sea. Depicted with wild dark hair swirling around her like a forcefield, she’s a powerful Greenlandic goddess responsible for keeping the ocean in balance.

When humans become too greedy and hunt too much, so the legend goes, she gathers the creatures of the North Atlantic together—seals, whales, dolphins, redfish, Arctic char and walrus included—and hides them in her hair, making humans go hungry. Only when a shaman takes a perilous journey down to the depths to appease her, will she relent and let the creatures out again.

The Mother of the Sea is painted on the walls of the hotels I stay in, and features in a local café I visit in Ilulissat, north Greenland, as well as the town’s stellar museum, the Icefjord Center. As well as being one of Greenland’s most important gods, she has immediate relevance today, as the country’s fledgling tourism industry continues to develop.

In 2025, a new, larger airport will open in the capital Nuuk, and in 2026, another will open in Ilulissat. That’s where I’m visiting, to find out how things are changing, and how local people are approaching something that challenges their own sense of balance.

I’m walking on a snowy trail with Danny Mølgaard, a local guide and owner of Disko Adventures, a travel firm he runs with his girlfriend and cousin in Qeqertarsuaq, Disko Bay. We discuss the tourism protests in Barcelona and what life is like in his small town of 845 people, where sled dogs howl in the midnight sun and you can tell what week of the year it is by spotting migrating geese.

We pass an astroturf football pitch with possibly the most unique views afforded to any football pitch in the world—icebergs and whales. We trek along the coast via a cave and a series of towering basalt cliffs that resemble something from Lord of the Rings. To our left, icebergs the size of islands float by in a pale blue sea.

“The myth reminds us that we have a responsibility to take care of our environment if we want to enjoy all the good things it gives us.”

- Anne Nivíka Grødem, Visit Greenland

We’re the only people on the trail today. It’s a route to Kuannit, the local town’s herb gathering patch. As we sit, overlooking the sea, to have a Greenlandic trail snack of dried narwhal, chocolate biscuits and dried halibut, a group of around 20 people approaches. They stop at the top of the cliff path and look down. And then, after their own snack, they turn back.

Danny breathes a sigh of relief. “We have an understanding as a town that large tour groups aren’t allowed down here,” he says. “The path is vulnerable and this place where the angelica grows is only for local people or small groups like us.”

It’s an example of something that I witnessed across North Greenland during my trip: Local people putting guardrails in place to protect their special and vulnerable spaces. Elsewhere, in Ilulissat, the UNESCO heritage area around its Icefjord Center is walkable, but only on boardwalks.

Signs warn that the ground is vulnerable, and you should not walk off the path. It also highlights something that I’ve found special about Greenland: The intimacy of tourism in this country, where local people share their personal stories with you, and have a deep sense of connection with their local places. It goes beyond the big blockbuster sights, icebergs the size of an island and the whales and birdlife.

It’s this idea of balance, and an awareness that runs through all things that an extractive form of tourism isn’t right: People and nature need to be in harmony. The national tourism board, Visit Greenland, has even developed a pledge for the country’s travel industry invoking the story of the Mother of the Sea to remember balance in nature, people and culture as it grows.

“The myth reminds us that we have a responsibility to take care of our environment if we want to enjoy all the good things it gives us,” says Anne Nivíka Grødem, CEO of Visit Greenland. “Through our pledge, we emphasize our dedication to promoting travel that respects and values our environment, land, and cultural heritage.”

This concern for the natural environment is second nature for many of the Greenlanders I met. Living in a country where the sea and the moorlands are your pantry; the fish, whales, muskox and caribou your sustenance; there’s an intimate connection with nature and a clear understanding about the value of protecting it. The tourist board has even coined a phrase for it—’authentic intelligence’, a cheeky nod to AI—because this deep knowledge and respect for the country is what turns a tourist experience here into something special.

Later in the day, I join Danny at a family gathering, and over a meal of mattak—the skin and fat of a whale, cut into a small, chewable lattice shape—fish layer cake, seal blubber and the silver darts of dried capelin fish, I hear a few more people talk about what the growth in the tourism industry is going to mean to them. The lady next to me is full of enthusiasm about it: “We’re excited about tourism,” she says. “Finally, we’re going to make some money!”

Small-scale tourism is possible and desirable here, because local knowledge is fundamental to a good tourism experience.

While there are voices questioning whether an increase in tourism will disturb their peace, the almost-Gold-Rush-like attitude to the new opportunities and what it might bring—especially if it could offer independence from Denmark—is the overriding sentiment I come across as I travel around Disko Bay. Almost… In the local museum, Lars, behind the desk, tells me that heliskiing and high-net-worth tourism are the key: Small numbers of high-paying tourists ready to spend are very much welcome.

Idrissia Thestrup, chief experience officer at Lost Horizon, a company curating bespoke travel experiences in Greenland, and former head of marketing at Visit Greenland, has noticed this interest too. “Since the news launched about the airports, local people have been investing in what is to come,” she said. “They’re buying boats and starting their own businesses. There’s optimism about it.”

Greenland does seem to be doing things differently, and small-scale tourism is possible and desirable here. With such a variety of scenery and fast-changing weather, local knowledge is fundamental to a good travel experience: If you don’t know where to find a good harbor in a storm or seek alternative solutions when the winds are too strong for a helicopter trip, travelers can, at worst, be at risk, or, at best, feel unlucky and disappointed.

For many firms, tourism is not yet sustainable from a financial perspective. It’s hard to have a year-round industry when travelers mainly visit for three months of the year, and when in some places, there isn’t even daylight for months at a time.

Only 85,484 travelers visited the country in 2022 and only 56,609 people live in Greenland permanently. The unreliability of weather—in part brought on by climate change—means that some of its most exciting opportunities can’t be available all year round. To an extent, small-scale local projects are the most likely to be successful, run as an extra job on top of other work.

On top of that, the Greenlandic government is currently debating how to regulate tourism companies with an eye on making sure that profits from tourism stay in the country, and that local people benefit from it.

Overtourism has been under discussion in a few places, notably in Ilulissat, which in the summer months can see its hiking boardwalks choked with cruise ship passengers. Cruise fees increased this year as a way to manage the influx of cruise ships. In 2023, August saw over 9,000 cruise visitors in a town with a population 4,670; in other parts of Greenland, cruise passengers can swamp the local population in a more dramatic way.

As an example, in Qaqortoq, south Greenland’s largest town, 47,000 cruise passengers visited in 2023—Qaqortoq is a town of just over 3,000 people. Given some cruise ships hold over 2,500 guests, the town can almost double in size for the short period that the boat is docked. Fewer visitors, or even this volume spread evenly across the year, would be greeted with open arms.

The ownership of tourism companies is also currently under discussion, around the idea that all tourism companies should have owners resident in Greenland during the tourism season at least. It’s a way of avoiding extractive tourism, whose pitfalls include tourism leakage—where money ‘leaks out’ to foreign owners and firms instead of staying in local communities.

What it means for travelers is that you’re unlikely to find a big red bus tour—there are few roads here anyway—and you’re far more likely to find personalized tourism experiences.

It underlines something I’ve been thinking about a lot: How the tourism industry, done well, isn’t just numbers on a balance sheet. It’s about pride, about people, and about all of us and how we live.

These include The Arctic Umiaq Line, a local Greenlandic ferry that plies the small communities on the west coast of Greenland, this year open for tourists and locals alike. It offers an authentic way to travel to these smaller haunts and meet local people as you do. There’s also Tasermiut Camp, a glamping set-up in the south of Greenland where you camp, fish and gather herbs with local experts; south Greenland’s horse farms, which offer lodging, hiking and riding experiences; and a plateful of fine dining restaurants across Ilulissat where you can eat local food, like halibut, muskox and minke whale, including Hotel Arctic’s new Brasserie Ulo.

Idrissia Thestrup’s guests have enjoyed these kinds of ultra-local experiences. “I love the traditional Greenlandic barbecue on the rocks,” she tells me, “where local meat is cooked on rocks from the fjord, often in seal blubber. You can’t find it in a catalog—I work closely with local people to develop these kinds of options.”

The sense of a tour created for you, not a cookie-cutter experience rolled out for everyone, makes it special. It’s something I’ve seen and felt all over Greenland. On my last day in Qeqertarsuaq, I visit Danny’s 19 sled dogs. He’s beaming with pride as he introduces them, slopping a bucket of fish out on the rocks for their dinner.

Run on an intimate level like this, Greenland’s independent traveler-focused tourism scene has the chance to give back to everyone in a relatively equal way, holding nature, tourists and local communities in balance.

And for those who want to explore one of the world’s finest adventure playgrounds, watch polar bears and whales, or discover a rich, rewarding and generous local culture, there are few places on earth like Greenland.

**

Laura Hall was a guest of Visit Greenland.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Laura Hall is an award-winning writer, journalist and author of titles including Time Out Copenhagen, Footprint Reykjavik and One Day, So Many Ways, a children’s book about how life is lived around the world. A former travel guide editor, she’s run communications for a travel start-up and led global content at a tourist board. She now writes about Scandinavia and the Nordics for BBC Travel, Kinfolk, Time Out, The Times, Lonely Planet and others.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: