Having lived under an Israel-imposed blockade and the threat of violence for most of their lives, sport and physical activity has become a form of escapism for many young people in Gaza. Before the pandemic, photographer Nicola Zolin headed to the Gaza Strip.

Night has already fallen in Gaza when the lights of a car coming over the hill illuminate the darkness of the city, revealing the shapes of two skateboarders heading my direction.

They both live in ‘Shati’, a refugee camp on the city’s outskirts along the beach, in which over 85,000 people reside in an area of only 0.52 square kilometers. It’s one of the most densely populated place in the world. Their families are already waiting for them to return home, but tonight is a special night: their Italian friends have arrived in town, so they’re allowed to stay out a little longer.

Roger, 25, whose full name is Mohammad Al-Sawalhi, and 19-year-old Nasrallah Abu Karsh, who everyone calls Nas, have been welcoming a group of young activists from Milan each year for the last five years. Backed by Centro Vik and the Italian NGO ACS (Association of Cooperation and Solidarity), which work on cultural and infrastructural projects in rural areas excluded from economic development, they entered Gaza with radical humanitarian ideas: building a skate park for the youth, recording music with local rappers, discussing feminist theories with women’s groups, cooperating with local artists, and more besides—all of it culminating in the ‘Gaza Freestyle’ festival.

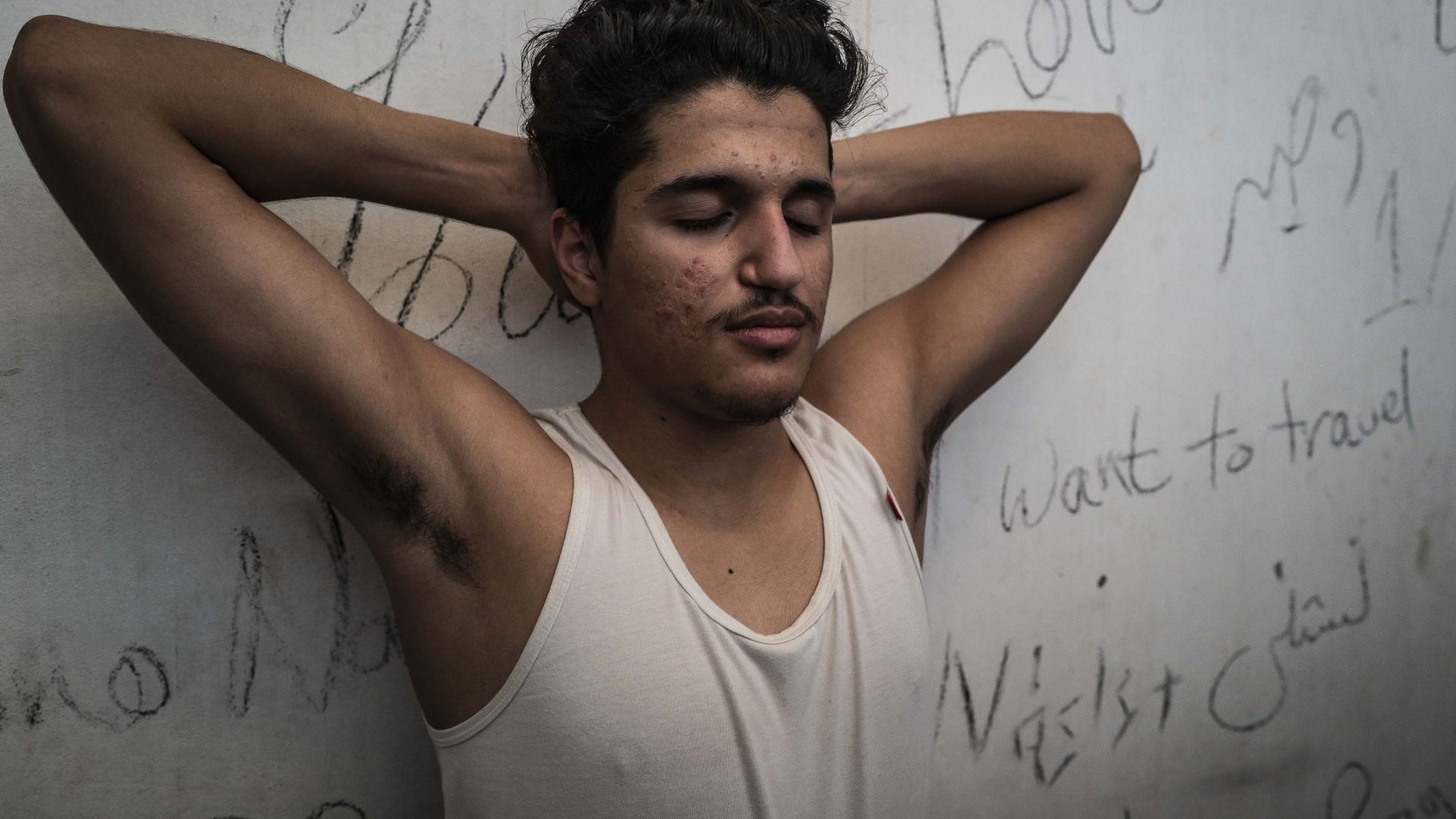

The cultural impact of the initiative has been impressive. “Skateboarding makes me feel I belong to nowhere,” Nas tells me one day at his home, sitting on the sofa, surrounded by artworks by his father Abdul-Atif.

Nas has never ventured out of Gaza City, not even to the nearby city of Khan Yunis. Scrawled in pencil over the walls of his bedroom are the words, “I want to travel” and similar phrases.

RELATED: How refugees saved Riace, the tiny Italian town that could

His father tells me about the accident that almost claimed Nas’s life, some years before, just a few meters from where we sit now. Nas was out playing with friends when Abdul-Atif heard an explosion. His son had been caught up in it. Nas spent weeks in the hospital unconscious and, when he woke up, he learned that 11 children had been killed in the blast.

He still encounters the parents of those children every day. “It’s like being a son for all of them,” Nas says while showing me around Shati camp. “All of these people have suffered the loss of loved ones. It’s the life in Gaza. There is no life in Gaza.”

Of the roughly two million people inhabiting the strip, 75 per cent of them are under the age of 25: a very young society, with little to no professional opportunities and a bleak future.

Later, I find Roger is sitting alone watching videos of Californian skateboarders on his phone. He looks disconnected from everything else. “I don’t wanna stay in Gaza,” he says when I sit down to join him. “I will come to Italy. What can we do in Gaza? There is nothing to do.”

I meet Alaa al-Dali, a sprinter from Rafah (and gold medalist in the National Cycling Championship in 2018), some days later at the Artificial Limbs and Polio Center (ALPC) in Gaza City, where amputees come to train with their prosthetics limbs.

In 2018, Alaa’s dream of competing internationally was shattered after his visa for the 2018 Asian games was refused. A few weeks later, frustrated, he cycled to the Gaza-Israel border to join the Great March of Return, a weekly protest that called for Palestinian refugees to be allowed to return to what is now Israel. “I went with my cycling kit to express my frustration of being denied as an athlete, demanding my rights as everyone else in the world,” explains Alaa.

According to Médecins Sans Frontières, between March 2018 and November 2019, more than 7,900 Palestinian demonstrators were shot, with live ammunition, by the Israeli army. On the day Alaa attended, as he stood with his bike a few hundred meters away from the fence, he was shot in the leg by a sniper.

RELATED: After the pandemic, how can we decolonize our travels?

The bullet almost disintegrated the bone in his leg, damaging the muscle, arteries and veins. He nearly went into hypovolemic shock due to the loss of blood, and had to have his leg amputated in order to survive. Nas and Roger consider Alaa a national hero.

There are other Paralympics teams in Gaza, with rosters full of people who have natural disabilities or injuries from the wars and the border protests. There are basketball teams, a karate and judo team for the blind, and a football team with players who’ve lost limbs. “All of these people have great benefit in practising sport,” Alaa says. “Doing sport is the best way to recover physical and psychological strength.”

Despite the efforts and enthusiasm of these sport teams, the chance of competing outside of Gaza is slim. Israel, in most cases, is not allowing people to exit.

Jumana Shahin is Gaza’s first female baseball player, and has been dreaming for years about traveling abroad with her team. The 24-year-old works occasionally as a freelance translator and stringer, and is frustrated by years of being unable to fulfil her dreams. “It’s so hard to have a normal happy life in Gaza,” she tells me. “I’ve studied all of my life and I can’t do what I’m prepared for. That’s why playing in a team is important for all us…it gives us unity and strength to persist in our daily struggles.”

—-

It was a very different world when I met all these people in Gaza, just before the coronavirus pandemic. The impossibility of traveling outside of our own borders, which is the everyday reality of the people in the strip, is easier to understand today, now that so many of us have experienced isolation at home.

Coronavirus infections in Gaza spiked before the end of 2020, severely affecting the healthcare system, but has dropped again as of January 2021. Jumana, Nas, and many young people in Gaza have spent much of the last few months inside. Roger, in the meantime, left the strip for the Greek island of Samos, from which he hopes to continue his journey to Italy.