How do you find a snow leopard in Ladakh? You find a snow leopard tracker to help you—experts who aren’t just helping travelers clap eyes on these magnificent felines, but working to protect them, too. Charukesi Ramadurai pays them a visit.

Want to find a snow leopard? These snow leopard trackers have a perfect record

You know what they say about amateur mountaineers? About how for each one that has scaled Mount Everest, there are a dozen hardy sherpas who have led, guided, cut paths, fixed ropes, and (literally) done all the heavy lifting? The same is true for snow leopard-trackers, as I learn first-hand during my visit to the trans-Himalaya region of Ladakh in north India.

At the crack of dawn, they sit on the cold ground with their eyes glued to their optical scopes, scanning the ridgelines in the distant hills for the snow leopard. All this in high-altitude territory, above 3,700 meters (12,139 feet) in below-freezing temperatures.

Snow leopards are found only in a handful of countries in Asia, and while details of the exact numbers are fuzzy for a variety of reasons—not least because they are solitary creatures that live across large swathes of barren, unexplored land—a survey conducted in India in early 2024 put the number at 718, with 477 to be found in Ladakh alone.

These numbers may seem small, but the snow leopard is one of the rare animals whose conservation status has been downgraded by the IUCN (International Union for the Conservation of Nature), from Severely Endangered to Vulnerable. While the move is highly contested by champions of this big cat, there is no doubt that the local community at Hemis National Park, my base, cares deeply for them.

The team at Lungmar Remote Camp have a lot to do with this, with a staunch commitment to both community development and snow leopard conservation. They work on educating locals on the need for conservation by highlighting both ecological and economic benefits, and help build predator-proof corrals to reduce human-wildlife conflict.

They believe the only way forward is to turn those who have traditionally viewed snow leopards as the enemy—killing their livestock and therefore, livelihoods—into friends and protectors. And through camera traps across the region, they also help scientific researchers trace and collar the snow leopards, to observe and study their behavior and ensure their wellbeing.

“If we are really lucky, we sometimes get to see the shan right from camp,” naturalist and co-owner of the camp, Abdul Rashid tells me … But there is no question of sitting tight and waiting for the shan to turn up; the trackers go out early and we follow them after breakfast, or even sooner, in case of any reports of sightings overnight.

That apart, I also know that in over eight years of operations, they have a near perfect record of sightings: No guest has gone back without seeing a snow leopard.

And that is a huge deal, since snow leopards are also among the rarest animals to spot in the wild. Not only are they elusive—as leopards generally are—but they are also the masters of camouflage, blending seamlessly into the brown and white background, rendering themselves invisible to the layperson.

Snow leopard-spotting needs the expert eye of trackers; locals who have grown up seeing these big cats and can locate this proverbial needle in the haystack. And the Lungmar team of naturalists are good at this—so good, in fact, that they are now training naturalists in other central Asian countries.

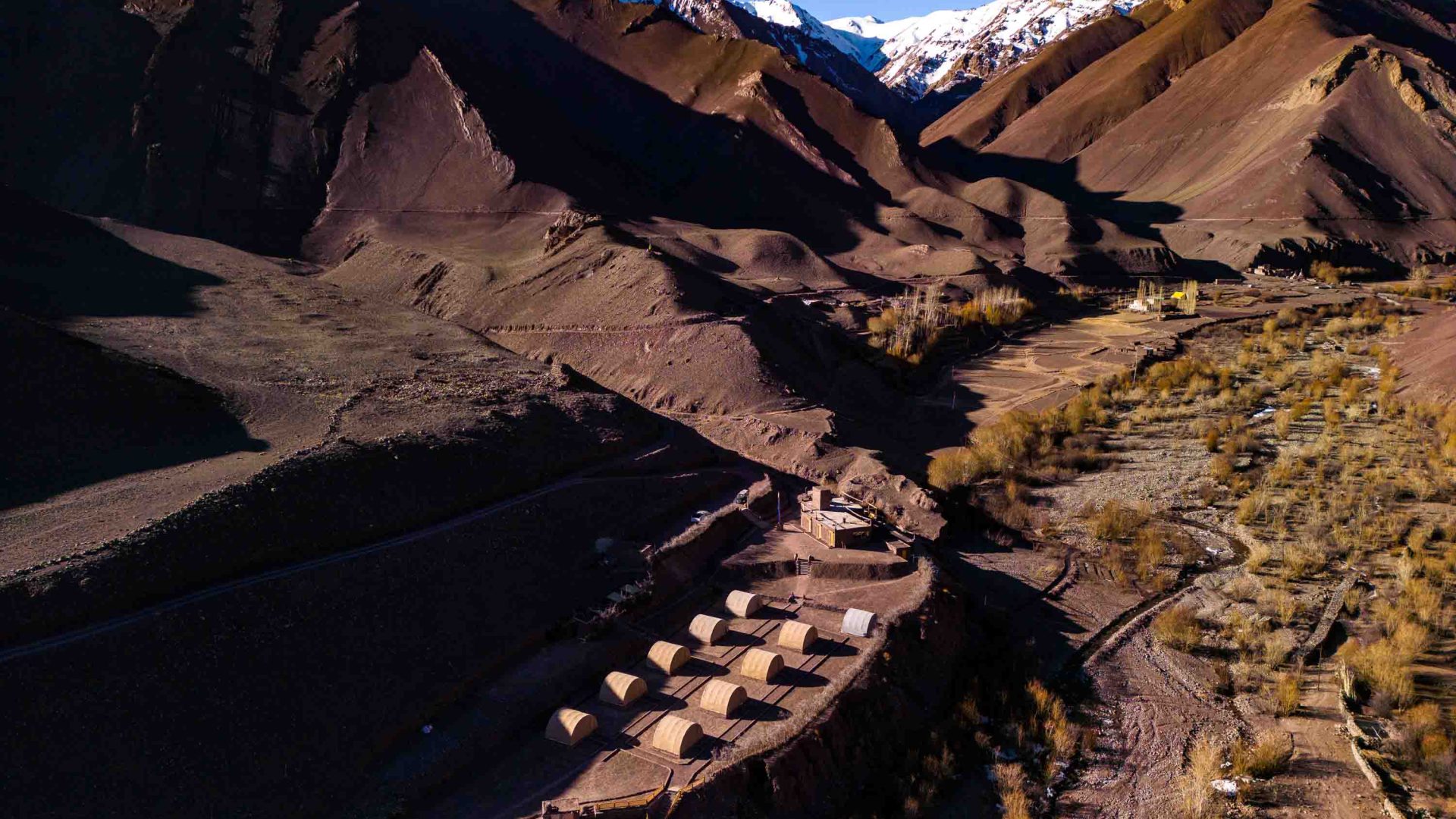

Named for the red soil around this area, Lungmar (‘Red Valley’) is a remote spot deep inside the protected territory of Hemis National Park. The landscape is bleak, but breathtaking—mostly brown, devoid of tree cover, and punctuated by gurgling blue streams, red rocks and the occasional patch of snow in the distance. The camp itself has been built with a focus on vernacular (local) Ladakhi architecture—think warm wood and cold stone—with a central common area known as the Sumdo Sarai at its heart, crammed with books, maps and photos on the theme of wildlife and conservation.

As expected, conversations around the Sumdo Sarai tend to center around the big cat: Near misses and disappointments, as much as actual sightings and the rare close encounters.

“If we are really lucky, we sometimes get to see the shan right from camp,” naturalist and co-owner of the camp, Abdul Rashid tells me during an initial briefing session, referring to the snow leopard by its local name. Rashid has been in the ecotourism business for many years now, from leading small group treks to now owning this boutique camp, his aim has always been to share the beauty of his homeland with others.

I should be so lucky. But there is no question of sitting tight and waiting for the shan to turn up; the trackers go out early and we follow them after breakfast, or even sooner, in case of any reports of sightings overnight.

I am humbled by the knowledge that without the trackers’ sharp eyes and sharper intuition, even the most experienced and expert wildlife enthusiast has no chance of locating these big cats in that landscape. Think of these trackers as detectives following clues—scarce, scant clues. Unlike in the Indian forests or the African Savannah, there is no way to follow pugmarks on the soil, scratch marks on trees, or alarm calls given out by hapless prey.

“The spotters need to know each ridge line; they need to understand the behavior of the snow leopard, where it will emerge from, and what it will do next,” Rashid tells me.

I particularly attach myself to Rigzin Chhosdol, the camp’s head naturalist, and one of the rare women in this field. Like the others, she has also seen snow leopards since childhood, but cherishes each new sighting even after seven years in the job.

And they do, sensing snow leopard presence from the slightest tail swish or ear wag. His business partner Dorjay Stanzin, considered one of the best trackers in the land, nods in agreement, “We have to keep our eyes open for anything that looks different from usual—like a small movement or vultures hovering in the air.”

Childhood friends Dorjay and Rashid couldn’t be more different from each other: the former shy and diminutive, while the latter fills up a room with his height and laughter. Neither of them has formal education or training in wildlife tourism, but care for the land and the leopard comes naturally to them. “People have always wanted to come to Ladakh to see snow leopards,” Rashid explains, “and my aim was to show it to them in an organized and responsible manner.”

I particularly attach myself to Rigzin Chhosdol, the camp’s head naturalist, and one of the rare women in this field. Like the others, she has also seen snow leopards since childhood, but cherishes each new sighting even after seven years in the job. Rigzin credits Rashid—a friend of the family—for her interest in ecotourism: “I have always heard exciting stories from Rashid—and other friends of my parents—and decided that I wanted to be a naturalist.”

While Rashid stepped up to convince her parents, Rigzin was surprised by how much she loved being out with people and showing them the natural wonders of Ladakh. Since the initial days, she has gone on to completing a professional naturalist course in central India and is now trying her hand at birding.

It is challenging, but not the toughest job out there, she claims. Many years ago, she tried her hand at the traditional shepherding that her parents (and theirs before them) did.

“I couldn’t manage even for a day,” she says, laughing. “That was tough. Here, I get to meet people from all over the world, and every guest brings a different energy that keeps me going.” Chhosdol also hopes that her presence will encourage more young Ladakhi women to work in wildlife tourism and conservation in their homeland. While she is one of the few women out on the field, the camp is practically run by a bunch of young, confident, English-speaking women from Ladakh. And she fits right in.

After two barren days, our luck finally turns. I scramble up a hill where the trackers have seen the shan, but he has vanished from sight before I make it to the top. But they know exactly where he has gone, and also when and where he is likely to reemerge. Then begins the waiting game, but the Zen-like calm of these trackers is reassuring. I take a deep breath and settle down.

Surely enough, a couple of hours after lunch, the shan comes out of his hiding place. But for the life of me, I cannot see him. Dorjay and Rashid take turns adjusting the scope. “Where is he?” I wail in increasing panic. By the time my eyes finally locate the shape, he has been standing there for several minutes—hidden in plain sight.

The sighting is glorious; the snow leopard marching with the confidence of a creature that rules the land. We have waited for over seven hours for these few minutes. And to think these spotters do this every single winter day.

This is not to say it is just all toil and tears; the mood at camp is almost always upbeat, cheerful. Even a veteran like Stanzin says the thrill never wanes. “I once had a close encounter with a leopard feeding on a kill, so close that I could hear his teeth grinding. It was actually scary, but it was also very exciting,” he recollects. “Yes, every sighting is special,” Rigzin adds.

Obviously, as my very first snow leopard sighting, this is extra special. And this would not have been possible without these dedicated folks, who don’t just locate them for eager tourists, but also ensure they continue to flourish in their natural homes.

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Charukesi Ramadurai is a freelance journalist currently living in Kuala Lumpur. Her work has been published in a number of international publications, including The Guardian, BBC Travel, South China Morning Post and National Geographic Traveller. She has a keen interest in wildlife and conservation issues, and in stories at the intersection of humans and the natural world.

Related

There are just over 600 wild Asiatic lions in the world… here’s where you can see them

Geologists to marine biologists: It’s time to celebrate the #WomenOfTheWild

Patience makes perfect: How (and where) to track a snow leopard

What’s it like cycling 150 kilometers through India’s prime tiger territory?

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: