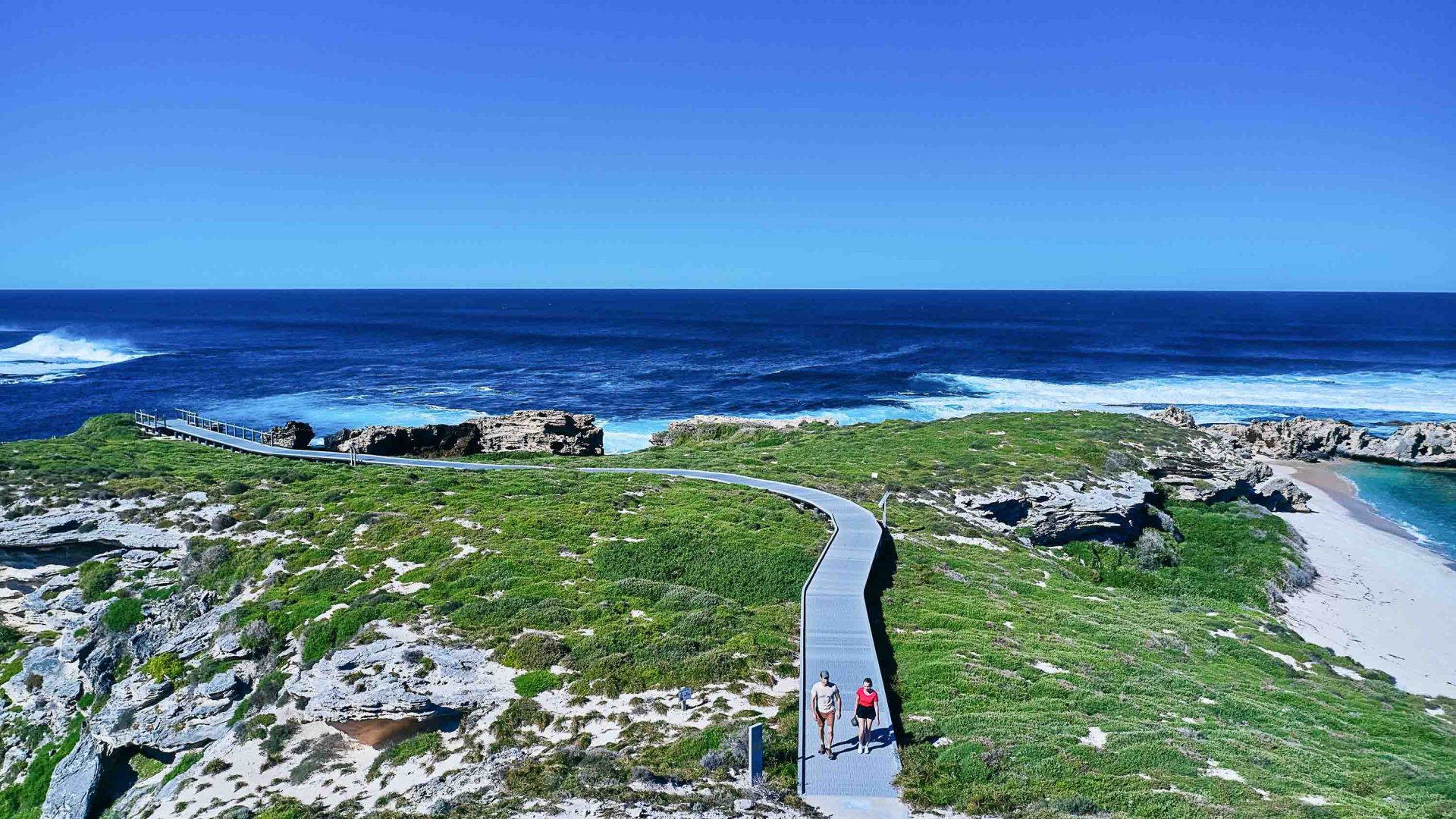

Do quokkas really smile? I’m watching a pair of these miniature marsupials foraging on a pristine beach at the edge of Thomson Bay on Rottnest Island, and the ‘grins’ that have brought them global selfie stardom play across their faces. When the Dutch colonialist Willem de Vlamingh set foot here in 1696, he thought the Australian island was infested with vermin and so named it ’t Eylandt ’t Rottnest (Rats’ Nest Island). Today, quokkas—and pristine beaches—are a major draw for the half million visitors who make the hour-long ferry crossing from Perth each year.

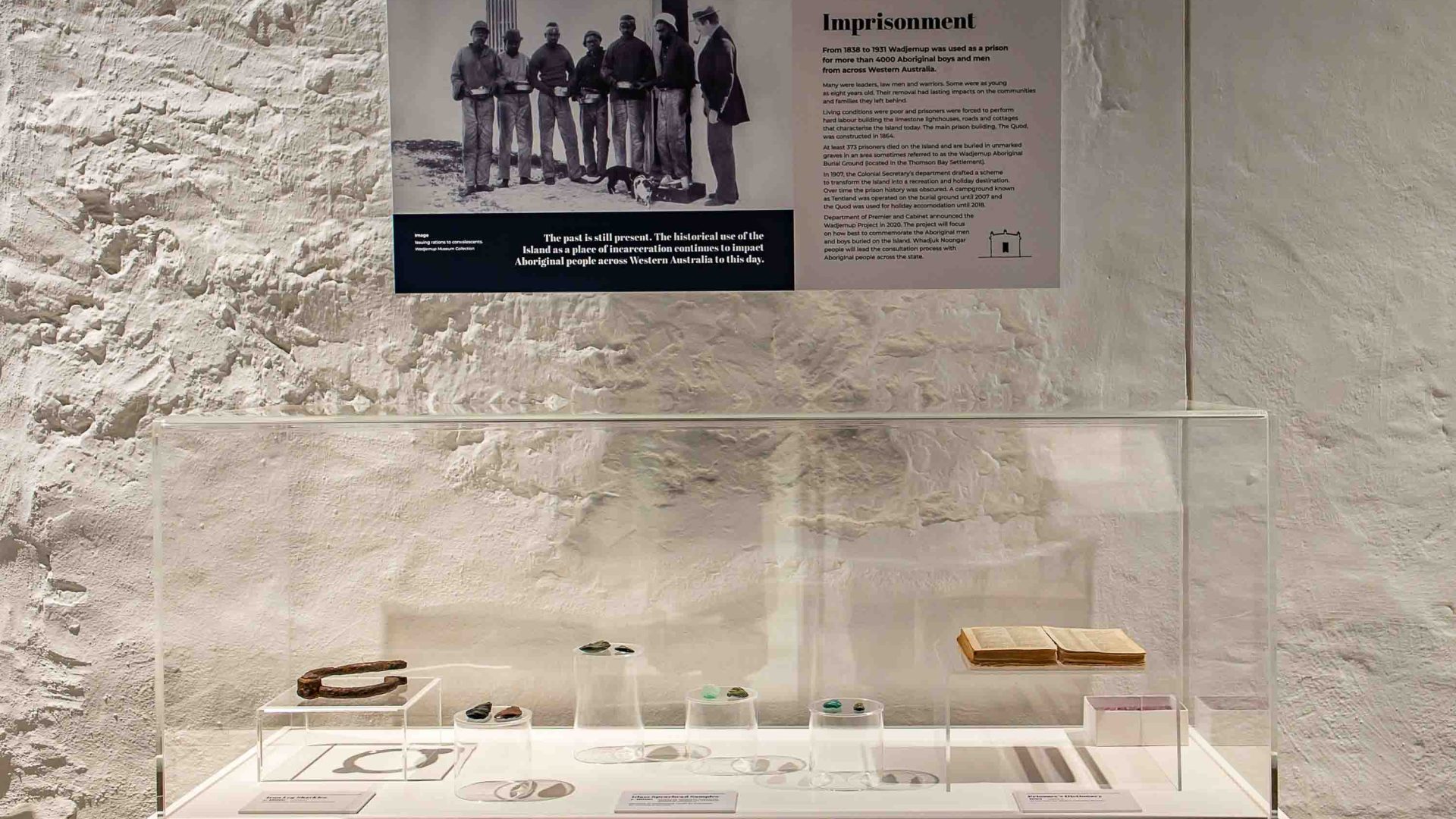

This is the Rottnest Island I had read about. But a few minutes’ walk from the Settlement (a cluster of historic buildings and tourist services), in a quiet patch of scrubland where the chatter of holidaymakers is lost to the breeze, is the Rottnest Island I had not. Here, beneath the shady pines, lie the unmarked graves of at least 373 Aboriginal men and boys, some of the 4,000 Aboriginal males from across Western Australia who were incarcerated on Rottnest—also known as Wadjemup in local Noongar language—between 1838 and 1931.

Some were as young as eight, others as old as 70, many of them were arrested and sent to Rottnest for traditional practices such as carrying spears or hunting. Hard labor, harsh conditions, disease, and violence all took their toll. A sign in the burial ground reads: “Kwidja baalap yey” (the past is still present). And now a new series of projects is striving to reconcile the island’s past with its present, and to shed light on the true Wadjemup story.