In a world drowning in cheap plastic souvenirs, how can a conscious traveler balance the impulse to buy with the ethics of consumerism? And where does that impulse come from? Nori Jemil explores.

In a world drowning in cheap plastic souvenirs, how can a conscious traveler balance the impulse to buy with the ethics of consumerism? And where does that impulse come from? Nori Jemil explores.

I’m not one for mindless shopping, and I’ve long had an aversion to malls, but there’s something so satisfying about picking up a travel keepsake. At times, the mementos have been useful, like a Chilean scarf for warmth on a breeze-blown beach. Other times, the souvenirs stand as memory-keepers, like the Mayan glyph necklace I bought in Mexico 15 years ago, and have worn ever since.

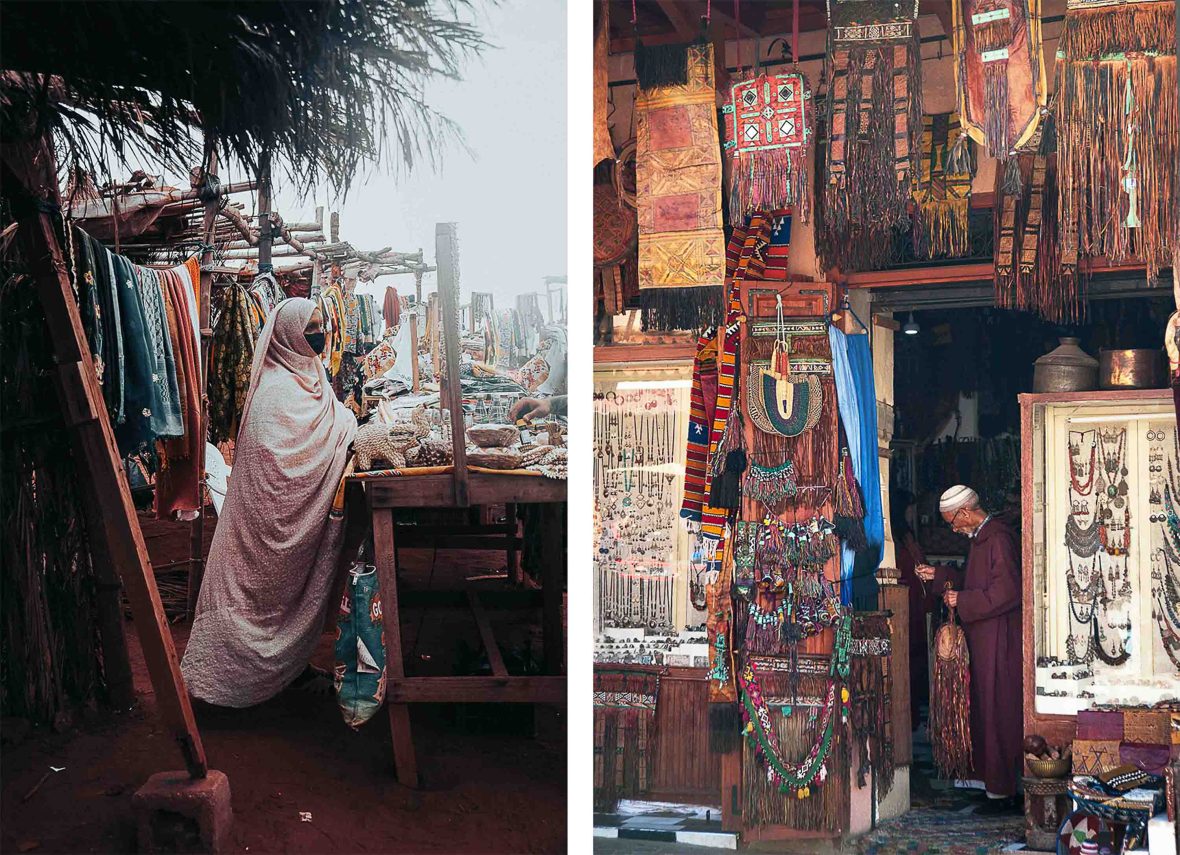

From the trophies plundered by invaders and explorers (yes, Lord Elgin, I’m looking at you), and medieval pilgrims collecting pebbles from the Holy Land, to shopping for shiny trinkets in a foreign flea market, bringing a memento back from our travels has long been accepted—perhaps even expected. But where does this impulse to buy and collect come from? And what does it mean for a world that’s already drowning in ‘stuff’?

The psychology behind retail therapy is well-documented. There are therapeutic benefits, like a chemical dopamine release, that come with buying objects simply for their aesthetic qualities. Then there’s the rush we get from the anticipation before buying. According to neurologist Shirley M. Mueller, “in this phase the pleasure center [of the brain] burns most brightly”.

Purchases that we deem unique light up different parts of our brain again. Research scientists used a functional MRI to prove that when shown extraordinary objects alongside commonplace things, our excitement is sharpened.

The way our brains are hardwired lends itself to the addictive nature of consumerism and collecting, but also to the excitement of shopping while on our travels—where unfamiliar items appear exotic and alluring.

While giving gifts might come with good intentions, are we actually just assuaging our own itch to consume without the guilt of ownership?

However not all souvenirs are created equal, and many sightseers are still, and often, buying ‘tat’—plastic items mass produced in overseas factories. In 2022 in the USA alone, more than USD21 billion dollars was spent in souvenir and novelty stores. And according to Rolf Potts, author of Souvenir, the vast majority of modern tat is made “inexpensively in China”.

Only recently on a city tour of Dubai, I and a group of other travelers were taken to a specialist gift shop. Given the price tag of the gold-threaded tapestries, it’s little wonder that Brazil-based student Liana Li opted for an affordable fridge magnet.

The desire to buy something small, as Liana put it, grips us all. And I have been just as guilty, having collected quite the stash of memory-inducing fridge magnets as a young traveler. During a big declutter just recently, I tried to keep only the ones that “sparked joy”, as Marie Kondo would say. Though perhaps I won’t even be able to keep those much longer, as according to the Wall Street Journal, refrigerators will not necessarily be built with magnet-friendly materials in the future!

That said, small mementos continue to spark big memories, and can be imbued with immense meaning. People have long collected pebbles from beaches (despite being told to take nothing but memories). London-based psychotherapist Ania Herbut says humans feel compelled to collect things as a reminder of happy times. In fact, we seldom hold onto items from an unpleasant trip or experience, save perhaps to serve “as a life lesson”.

And while the plastic ‘tat’ trade is not doing great things for the environment (hello landfill), the selling of artisanal wares can be an economic lifeline for many communities. Kate McWilliams, a trustee of the LATA Foundation, a charity raising funds for social and environmental projects in Latin America, has seen firsthand the positive impact of mindful souvenir selling.

At La Chureca, Nicaragua—what was Central America’s largest open-air landfill site—women have been empowered to start small handicraft businesses. “For visitors, this offers something truly authentic [to purchase],” says McWilliams, “as well as providing economic benefits… and the preservation of traditional techniques that often have been passed down by generations.”

I’ve seen it myself over many years living in Latin America. For a while, I collected textiles, not least because they were portable and had a distinct cultural identity, but more importantly because buying directly from the maker is hugely satisfying. The work of a young painter from a Rio favela still hangs on my wall, as do textiles from Guatemala and the Guna Yala islands.

I’ve also bought many souvenirs as gifts. In fact, I’ve bought so many that my otherwise gracious mum recently announced: “I don’t need any more knick-knacks!” It might have been the sheer number of ornamental cats that prompted her bluntness, though my parents do appreciate the Turkish items displayed discreetly around their home—a reminder of my father’s culture.

But while giving gifts might come with good intentions, are we actually just assuaging our own itch to consume without the guilt of ownership? Or maybe it’s simple altruism at play, where the act of giving activates pathways in our brains that release oxytocin and generates a feeling of connection.

Would I choose this item as a tribute or amulet to be laid to rest with me in the style of a Viking or Pharoah?

The Japanese custom of omiyage sees travelers bring small items, often locally-packaged food parcels, back to share with their co-workers, friends or loved ones who were unable to make the trip with them. This resonates with me, having lived in another country from my family for so long. Picking up small gifts for them on the road has kept them close.

So what should we do—as conscious travelers—in the face of a tempting street market or local gallery or specialty gift shop? I think the answer is to buy generously, but mindfully, from people who will benefit directly.

And if we do find ourselves drawn to a piece of ‘tat’, perhaps we need to stop and ask: Does this souvenir spark enough joy and meaning for me to want to keep it forever? Would I choose this item as a tribute or amulet to be laid to rest with me in the style of a Viking or Pharoah? Somehow I can’t imagine anyone wanting to take their final journey alongside a fridge magnet.

That said, I’m still hanging onto my favorites… until I buy a fancy new fridge, I guess.

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Award-winning photographer and travel writer Nori Jemil lives between London and Perth, Australia. She writes for numerous publications including Rough Guides and National Geographic Traveller UK, teaches travel photography courses, and is the author of 'The Travel Photographer's Way', published by Bradt in 2021.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: