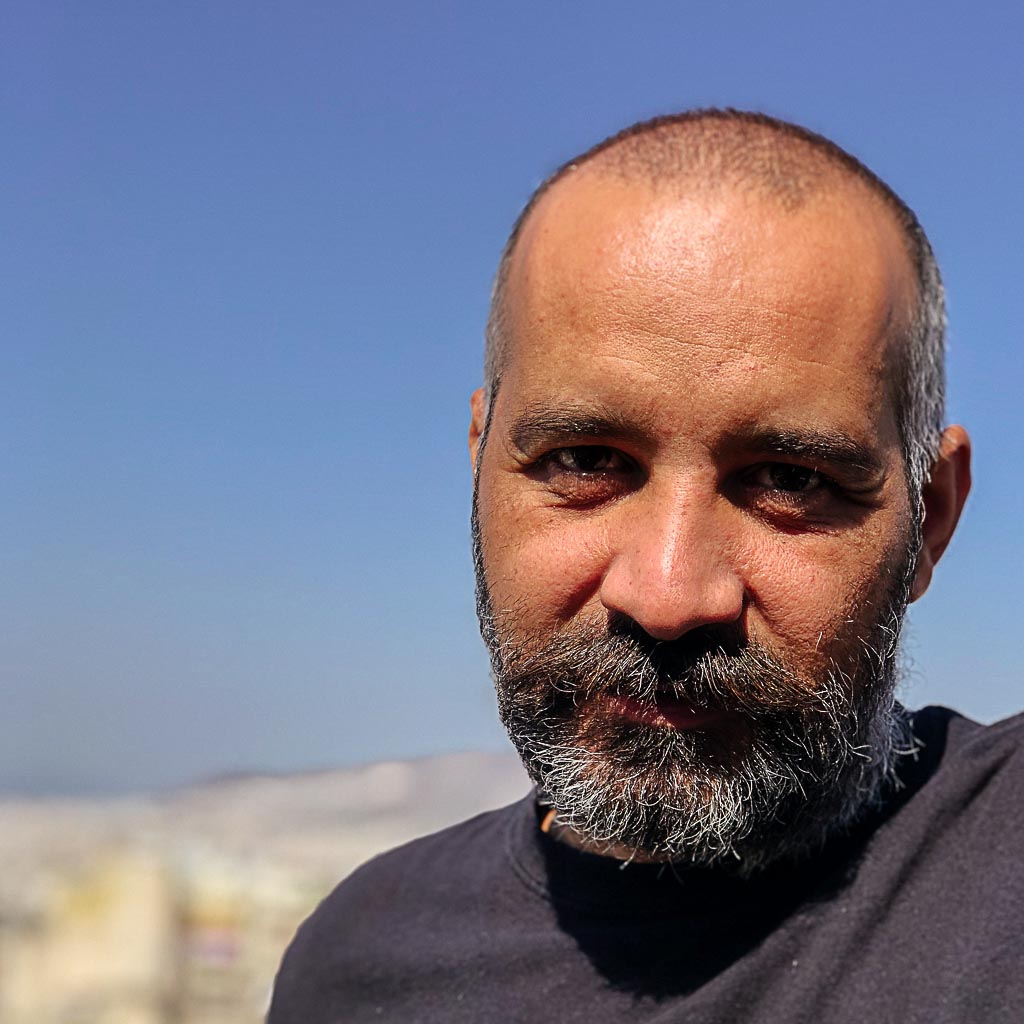

All photographer Angelos Giotopoulos wanted was to return home to Melbourne and visit his terminally ill mother. But, thanks to the COVID-19 pandemic and Australia’s strict 14-day hotel quarantine policy, his journey didn’t go quite the way he’d planned.

I found out my mother had died over the phone, alone in a Melbourne hotel room. She was in hospital just 22 kilometers away. But Australian authorities wouldn’t let me visit her on her deathbed. When I received the news, I was three days into a 14-day quarantine, waiting for my request for an exemption on compassionate grounds to be approved.

I took it badly. I was in shock, I was numb, I couldn’t move. I had traveled to Australia from Greece to grant my mother her dying wish: to see me one last time before she passed. I just couldn’t believe this had happened, I was certain I would be able to see her.

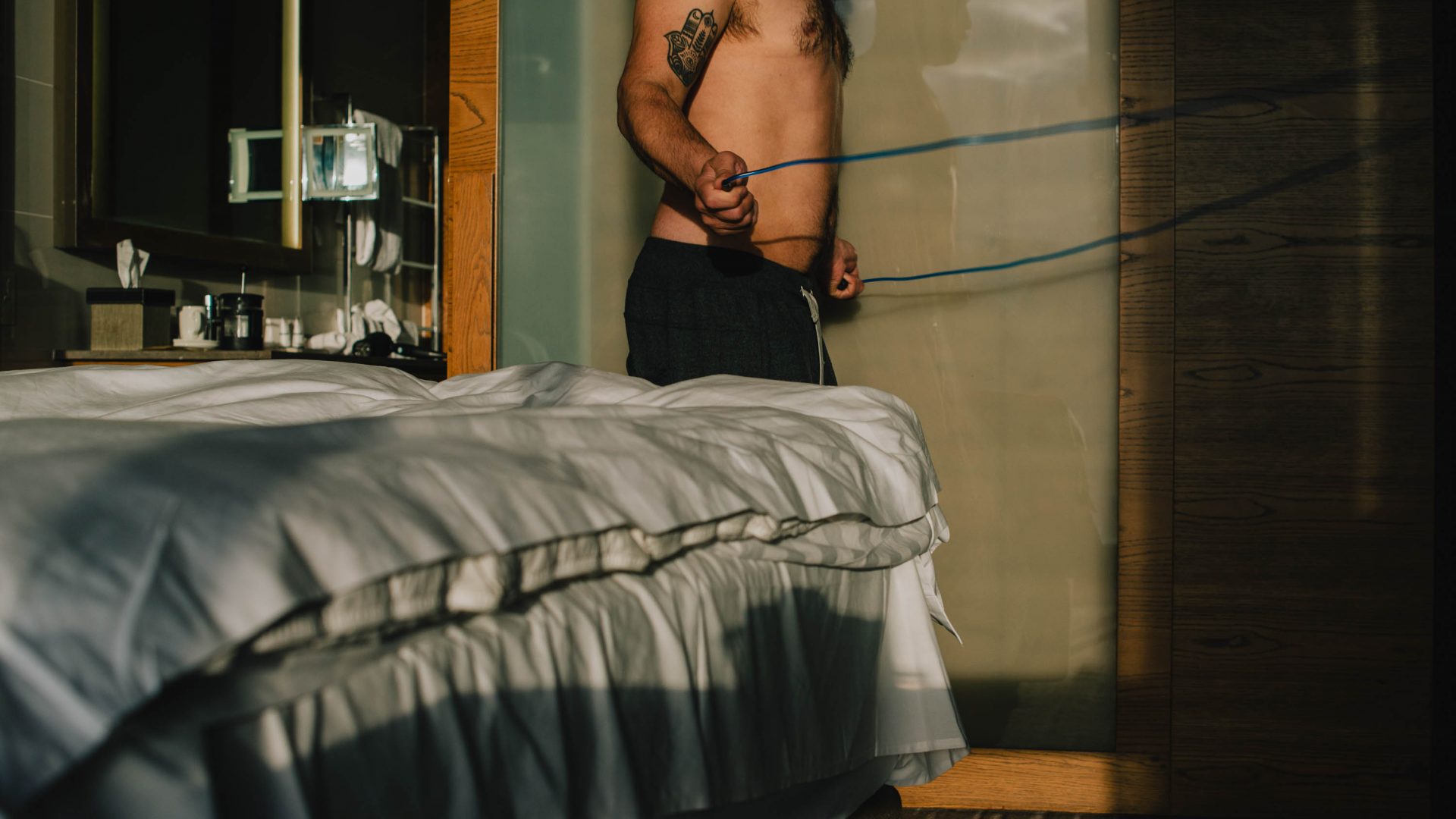

I had to face grieving, alone, in a 30-square-meter hotel room, in isolation, without any physical human interaction. Only four walls and one window that wouldn’t open. 11 days would pass between receiving the news that my mother had passed and properly interacting with another human being. Grieving in isolation is something I would never wish on anyone. It is totally inhumane. The experience has changed me—for good or ill, only time will tell.

Traveling during the coronavirus pandemic is a challenge at the best of times. But my advice for anyone thinking of going to Australia—for whatever reason—would be: don’t do it. There is a fortress mentality which has developed in recent years. Yet, the realities of ‘Fortress Australia’ are usually invisible to Australian nationals (like myself) or other (white) Westerners.

RELATED: For travel to return, we need global vaccine equity

Normally, it is only refugees and migrants who experience the brutality of this border regime. But now, thanks to the pandemic, everyone is at the mercy of an indifferent bureaucracy. In Australia, compulsory 14-day quarantine on arrival is officially referred to as ‘detention.’

I had the privilege of experiencing this firsthand when I embarked on a journey from Athens, Greece, where I live and work, to Melbourne, Australia, where I grew up. My mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer in February this year and doctors told her she had a year to live. But her condition quickly began to deteriorate.

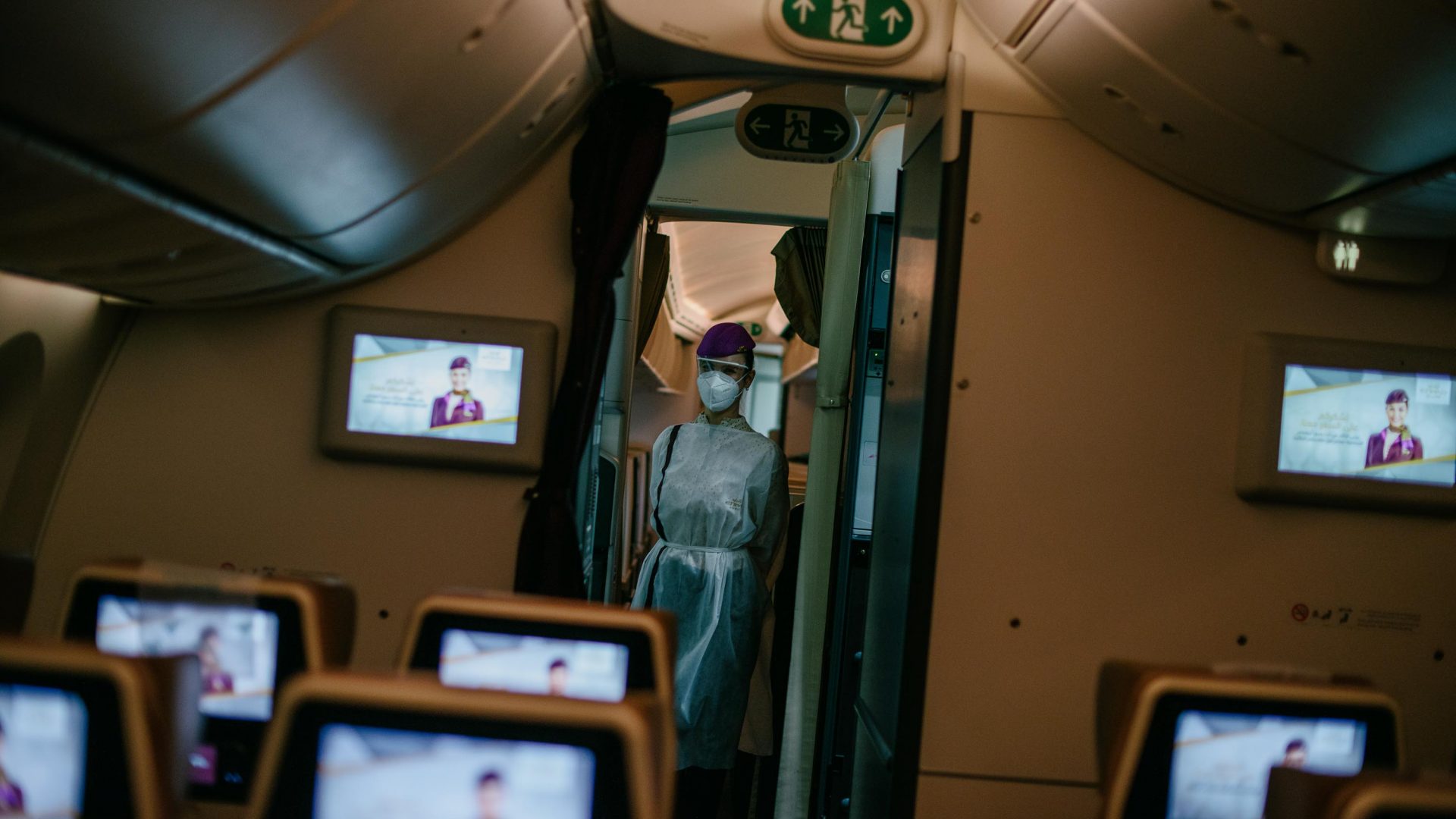

Upon arriving at the hotel, we were ‘welcomed’ by hotel, police and military personnel. Everyone inside was in full PPE—and you could tell they meant business. It is a prison-like regime. You are confined to your room and not allowed to leave for any reason. Food is delivered three times per day. You hear a knock on the door then must wait 15 seconds before opening the door and picking up your paper bag, which contains just enough food to sustain an adult.

You’re not allowed to leave your room, let alone go outside. Nobody enters your room, either. If you need fresh towels or to change your sheets, you have to call the front desk to make a request—and each request is met with extreme suspicion. The closest thing to human contact is the PCR test, conducted every four days. It was like being operated on by a robot doctor following the same lines of code every time: name, date of birth, nasal cavity swipe, shut the door. Then you can watch them through the peephole, cleaning the surface of the door outside.

Little by little, you start to feel like you have done something wrong, that you are a problem to the rest of society. They keep reminding you that you are in detention—from the ‘welcome package’ you receive and in any interaction with staff. There are 24/7 security patrols. I opened my door to photograph the corridor and immediately received a stern phone call reminding me that I was only allowed to open the door to pick up food, sheets or laundry.

Now, there are merits to the strict regime Australia has put in place. To date, 1,050 people have died of COVID-19 in Australia. Meanwhile, other countries have seen more than that number die on just a single day.

Like any decent person, of course I would be happy to spend two weeks of my life in quarantine to help contain a virus that has spread death and chaos throughout the world. But, as I told the authorities, those two weeks could very well be my mother’s last two weeks on this earth. Every official I spoke to in the process of applying for a compassionate exemption tried to hide behind their desks, hoping it would all blow over. Or that they could pass the responsibility to someone else. I wasn’t asking for anything that hasn’t been done before: people have been given permission to see their dying parents in full PPE gear. I felt like I was being avoided. And the clock was ticking.

The following days didn’t get any easier. I was so desensitized to my surroundings, it was like I was in a waking coma, just working off basic motor skills. Everything about the experience was abnormal. I tried to keep some kind of routine, something to make the days go faster: exercise in the morning, read a book, do some editing on the computer. I finally managed to finish a short film I had been working on for a couple of years, which gave me something to channel my energy into.

RELATED: Vaccine passports aren’t perfect, but how else should we reopen travel?

But I couldn’t hold my emotions at bay. Despite trying to keep yourself occupied, there is only so much you can do in a single room, 30 meters square. The demons were raging. I’ve done my best to deal with these powerful feelings of loss and injustice and tried to remain as stable as I can. I won’t get over this. But I will have to learn to accept it, somehow, someday… The emotions that hit me looking back over the images now are double-edged: what I captured was out of this world, but I had to experience something really detrimental to do so.