The pace of change isn’t often kind to traditional communities. Yet through quiet moments of everyday life, photographer Kin Coedel shows how nomads high on the Tibetan Plateau use ancient craft to harmonize with the modern world.

The pace of change isn’t often kind to traditional communities. Yet through quiet moments of everyday life, photographer Kin Coedel shows how nomads high on the Tibetan Plateau use ancient craft to harmonize with the modern world.

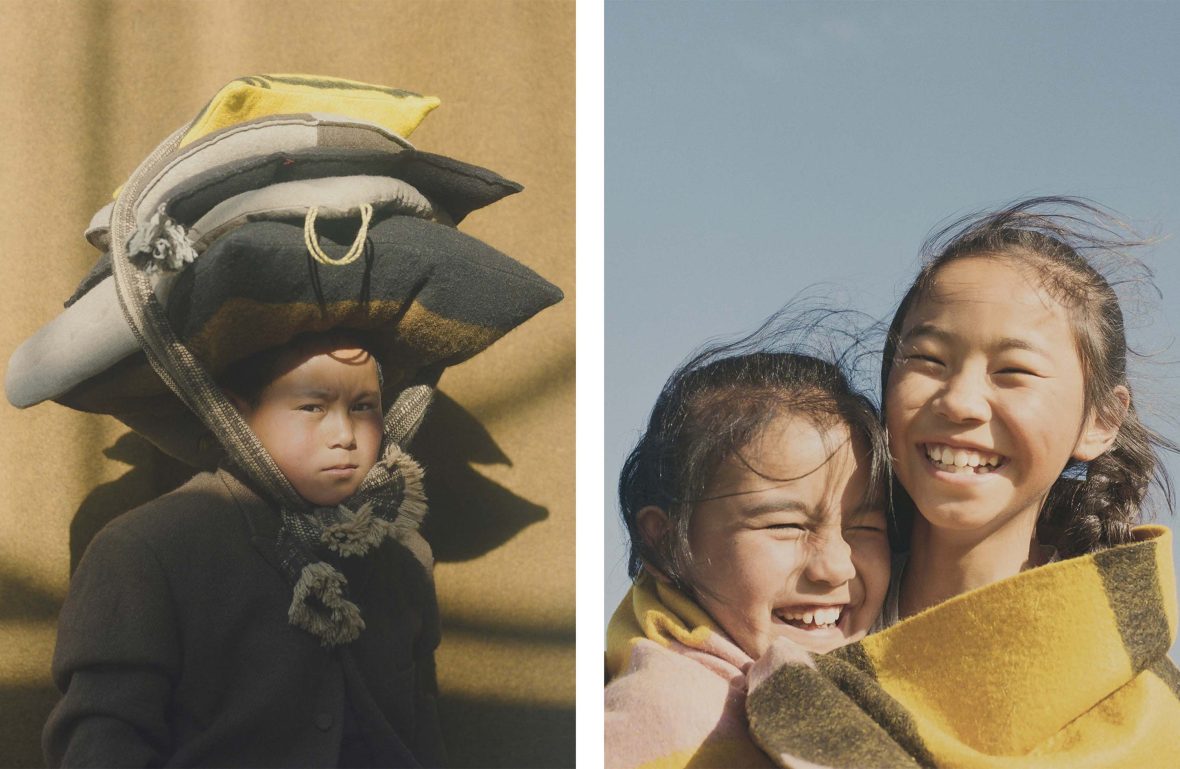

Age-old nomadic communities on the Tibetan Plateau and the surrounding Tibetan Autonomous Regions are experiencing a rapid social and economic shift. Telling this story through the lives of the country’s traditional weavers of yak khullu textiles—made from the soft down hair grown by yaks in the winter—photographer Kin Coedel showcases how these changes manifest in everyday life.

Making five trips to the region throughout 2021—the longest being two and a half months—the pandemic was Kin’s catalyst for traveling to Tibet. Living in Los Angeles and unable to continue his work as a commercial fashion photographer, he decided to base himself in Shanghai until conditions improved. Despite having a Chinese passport, it was Kin’s first time living in the country after being raised by Hong Kongese parents in Canada.

Kin soon agreed to a job for a local fashion brand to go and document the culture and practices around yak khullu—a luxurious textile increasingly compared to refined products like cashmere and merino. After spending two weeks in Tibet, he found himself enamored by the place and its welcoming community.

“This job reignited my interest in traditional textiles again,” says Kin, who previously worked as a fashion designer in London. “Knowing Tibet, with its rich nomadic history and generational practice producing yak textiles, I was instantly drawn to it.”

“Every day had new things to explore and new stories to hear about, but the series is still very much tied to these people’s everyday existence.”

- Kin Coedel

Back in Shanghai, Kin researched more about Tibetan culture. After contacting local religious groups, his search expanded to remote Autonomous Regions within Sichuan, where Tibetan Buddhism closely intertwines with daily life. Soon, he came across Norlha Atelier—a luxury clothing studio founded by a mother and daughter that employs over 130 people in Tibet; all nomads or former nomads. Following an exchange of messages, Kin was warmly invited to visit Ritoma, the village on the Tibetan Plateau where Norlha is located, at 3,200 meters (10,500 feet) above sea level.

“This village is essentially a female-run community, where generationally they are all weavers and spinners,” explains Kin. “They are still making textiles in the most traditional way, with no modern machines.”

Creating images that would eventually become his series, Dyal Thak—meaning “mutual ties” or “a common thread”—he witnessed how the evolving world challenges Tibetan nomads’ traditional way of life. According to Kin, China’s soaring population and industrialization in the post-revolution era meant Tibet’s economy, based mostly on agriculture and textiles, had little chance of competing.

“What can they produce in this geographic region where very little grows, and they can only manufacture a few things?” Kin asks. “For years they struggled, but then Norlha Atelier, this particular example, found a way to convince the rest of the world that its handcrafted products are special—a luxury worth seeking out.”

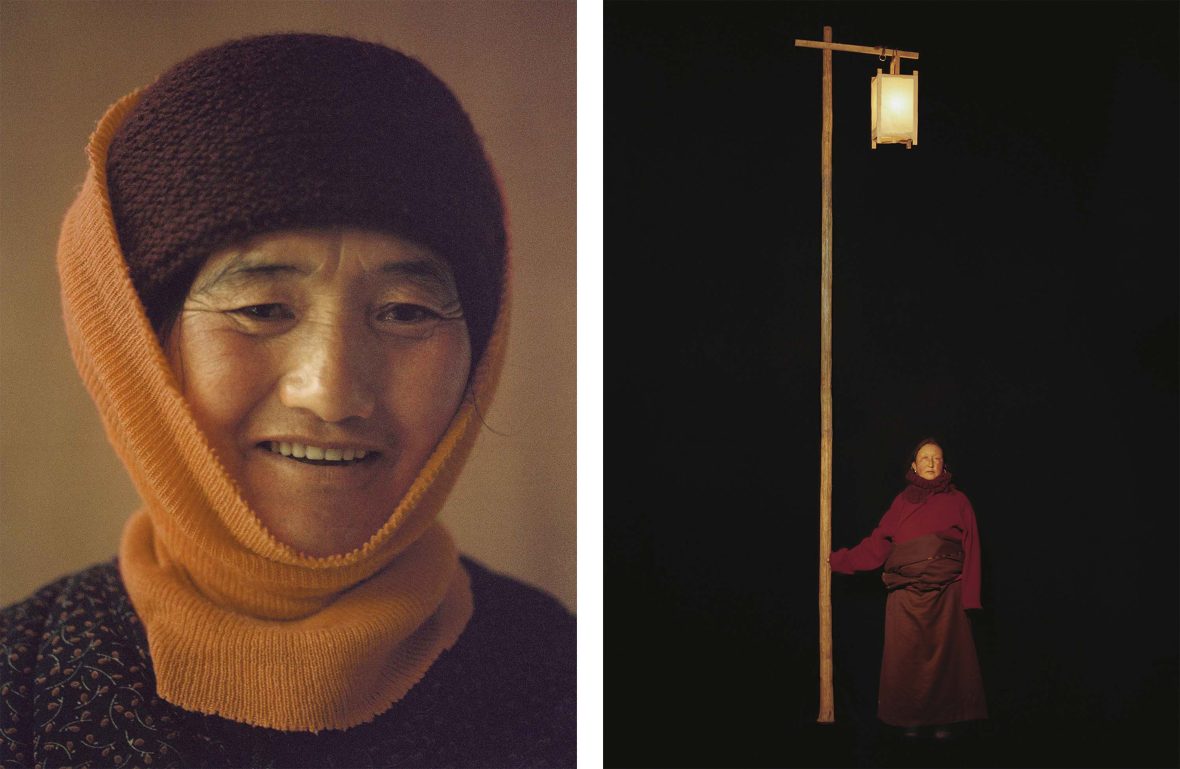

Fascinated by how this venture in a remote region of Tibet carefully balances ancient customs with modern sensibilities, Kin stayed to document this emerging narrative. Rising early in the morning, he would have breakfast with the weavers before wandering through the atelier, searching for overlooked minutiae. He also meandered into the surrounding provinces, observing lives revolving around community, agriculture and religion.

“Every day had new things to explore and new stories to hear about, but the series is still very much tied to these people’s everyday existence. Whether they’re working in the atelier as textile workers or spending time with their families, who could be nomadic farmers, hunters or riders, they all had different stories to be told.”

Learning about the esoteric forces that govern the lives of Tibetan nomads, one aspect that stood out was the significance of the moon and the lunar calendar. While farmers on the plateau use its position in the sky to plan pasture work and harvest, locals also enact religious practices depending on the phase of the moon’s guiding light. Inspired by this facet of Tibetan culture, Kin was driven to highlight the community’s profound connection to the moon.

Part of the narrative captured through the photographic series challenges the perspectives told and retold by western journalists throughout history.

“I spent three days watching the moon set, taking into account its time, elevation and angles. Then, I had to find the right place on the plateau that lined up perfectly with the rising moon. On the final day, a local girl woke with us at five in the morning and posed on the mountain.”

Although that particular image was directed, Kin has continuously played with notions of candidness throughout his work for numerous high-end fashion brands. This aesthetic carries through to Dyal Thak, as he once again blurs the lines between staging and documentary to differentiate his photography from photojournalism—a title Kin doesn’t want nor sees fitting for his work.

“I’m not a journalist because I’m not using local elements like people and culture to tell facts, but to create a different narrative—an escape, a dream,” explains Kin. “I want people to look at my images with a sort of uncertainty, like ‘Oh, how did he get such an intimate image? Is it just a candid moment, or is everything staged, organized and prepared?’”

For Kin, part of the narrative captured through Dyal Thak challenges the perspectives told and retold by western journalists throughout history. Frustrated with how much media attention on the region focuses on well-worn topics like foreigners trekking in the Himalayan mountains, he believes we can learn far more powerful lessons from the quiet beauty of life in the Tibetan Plateau.

Political, social and environmental concerns have seen an exodus of nomads from the steppes to the city.

While it wasn’t a deliberate decision to defy these viewpoints when embarking on the series, Kin says his background and past experiences have led him to reject many of the classical images he sees of East Asian culture. Although he considers many of these images shot by “mostly French and British photographers” striking in their composition, he often senses fear and suspicion in the eyes of those depicted.

In search of images that resonate with honesty and intimacy, Kin’s top priority when photographing people is communication. Kin works alongside a local partner—usually a person the community knows and trusts—who translates Kin’s Mandarin to Tibet’s regional dialects, ensuring those he wants to photograph feel at ease about his ideas and intentions.

“Every portrait, every intimate moment, I have someone explain what I’m trying to get. That way, the person I’m photographing understands,” says Kin, drawing parallels with directing models on a fashion shoot. “Sometimes it’s just talking to feel a person’s energy and make sure the mood is light so work doesn’t just feel like work. It’s all a process of exchange and communication.”

In neighboring countries like Mongolia, political, social and environmental concerns have seen an exodus of nomads from the steppes to the city. However, Kin believes local businesses can leverage international interest in traditional practices to maintain their existing way of life. Taking the weavers at Norlha Atelier as a shining example, he suggests their approach represents a new paradigm in how time-honored communities can protect and benefit from their customs in the present-day world.

“It’s about going back to tradition, to the handcraft or the herbs they can collect on the mountain, the way they raise their cattle,” says Kin. “I don’t have a conclusion nor all the know-how for how it’s done, but I believe we’re in the middle of this economic change for the Tibetan community.”

***

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: