Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

When it comes to Instagram, most travelers focus on filling their feed with photos. But National Geographic’s Neil Shea was more interested in filling his with words. Now, thousands of followers flock to his feed for his uniquely poetic brand of bite-sized travel storytelling.

In 2006, Neil Shea took a deep breath and attempted his first elevator pitch. Literally. He was riding an elevator with an editor from National Geographic, and she was looking for a writer to send to Iraq. Neil had never been in an active war zone before. He was a wilderness guide-turned-journalist, a lecturer, and staff scribbler at Nat Geo. What did he know about Baghdad? Before he knew what he was doing, he blurted out: “Send me.”

That adventure led to others, as Neil journeyed the world for National Geographic—Iraq, Afghanistan, East Africa—reporting on conflict and social justice, and the movement and displacement of people. But it wasn’t until 2013, when he and photographer Randy Olson were traveling through Turkana County in Kenya, that an editor said, “Hey, you should check out Instagram.”

It was a suggestion that would come to help define Neil’s career.

Because Neil doesn’t just write Instagram captions. Supplemented by Randy’s photography, Neil pioneered a new form of social media journalism. To refer to them as captions almost does them a disservice—his contained, beautifully crafted prose poems hurled readers so close into the action , they could hear the flies buzzing. The pair would post these vignettes at the same time each day and often serialize them, so one story would unfold over several days and several posts. Neil and Randy had invented long-form Instagram. And National Geographic’s feed went berserk.

RELATED: Meet Iran’s defiant hitchhiking youth

We sat down with Neil to ask him about life, words, social media, and the importance of a good notebook.

James Shackell: How did the Instagram stuff begin?

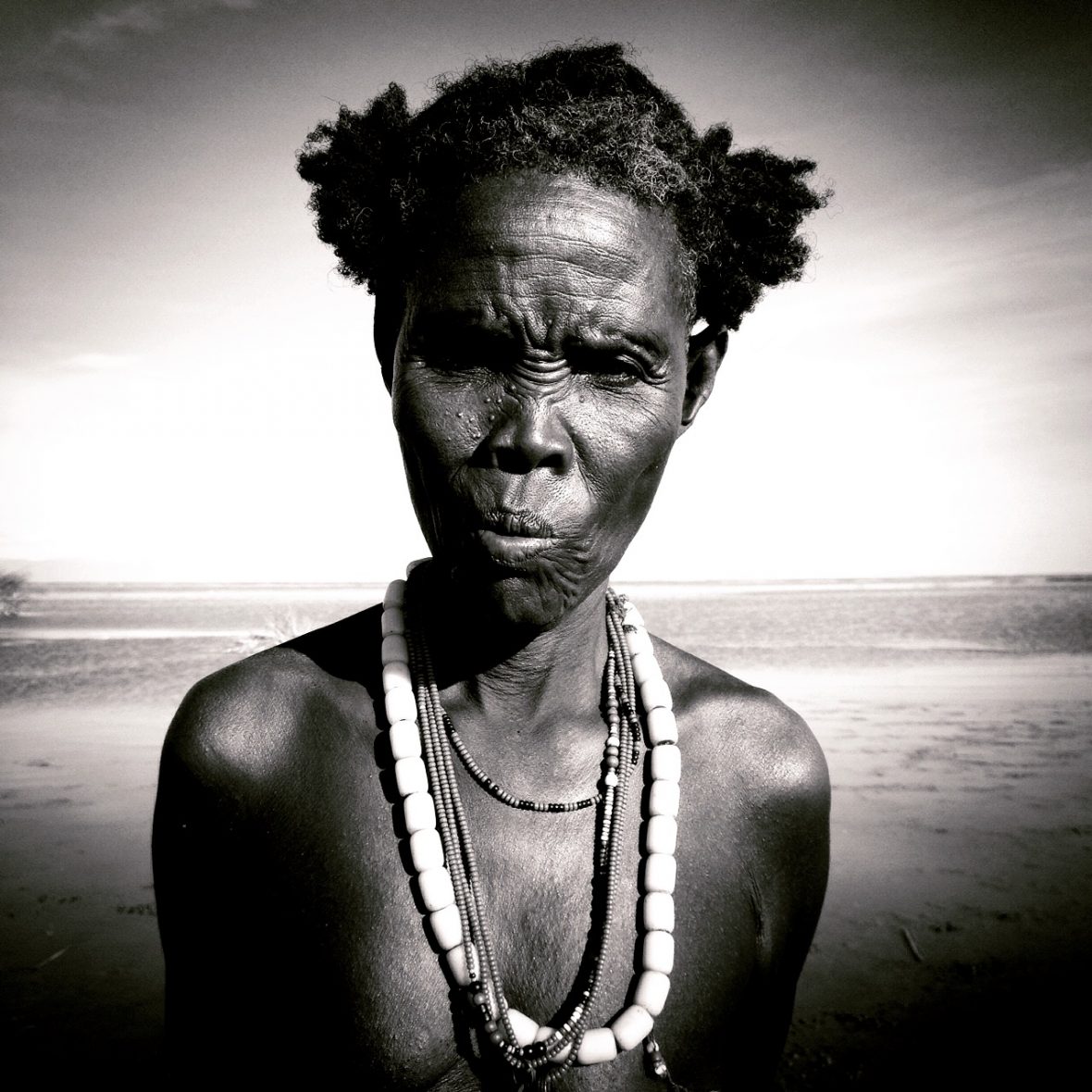

Neil Shea: Randy Olson and I first worked together on a story in Ethiopia’s Omo River Valley. We spent three months and two trips down in this undeveloped part of the country, traveling through some amazing landscapes. We became really good friends.

The Omo River spills south into Kenya, so we thought, let’s take the story further and follow the river south. So a few years later, we came back and did Turkana [a county in the former Rift Valley Province of Kenya]. My editor at the time said, “Hey you should try Instagram.” And my first thought was, ”Instagram? All those cats and selfies? What am I going to do, take pictures of food?”

Then I looked into it and realized people were doing some cool things on there. Photographers digging through their photos and publishing seconds and thirds [unpublished photos]—stuff people wouldn’t usually see. And I thought, ‘No-one’s using the caption space. Why don’t I start doing that?’

National Geographic wasn’t really paying much attention to Instagram at the time. You know, there wasn’t anybody back in New York watching what we were posting. Randy and I didn’t ask permission. We just started doing it. For a while, we worried … you know, ”What happens if somebody notices? Will they shut us down?” And fortunately they liked it, and they let us keep doing it.

Do you see any advantages to using Instagram as a storytelling platform?

Well I was always taking photos, because that’s good for your journalism. I always take the portrait of someone I just interviewed. And that’s how it began.

You’d come home with these stories and most of them never make it into the magazine. In a long feature, you’re always fighting for space. Stuff gets cut all the time. These anecdotes in your notebooks, you’d have 50 or more just sitting there, and I was feeling frustrated with that. I’d blow off steam by writing emails and dispatches to my editor—short little stories written in the body of an email. And that was one way to stop these little stories from vanishing.

How would you categorize your style of journalism?

I think Instagram is mostly influenced by poetry for me. I read a lot of poetry. That was certainly the model.

When I was thinking about the posts, way back at the beginning, I didn’t want it to be standard journalism. I knew they had to be a different type of storytelling. But it’s not like I invented anything – the poets were already there.

At the start, people wanted to call them ‘Insta Essays’. But that’s awful. It just didn’t work. I’m not gonna try to come up with a name for this stuff. If you look back at the early stories, we tried different hashtags like #instaessays. But they were all terrible.

The tough thing is that no-one is making any money off this. You do it because it’s fun. You’re doing it because you want to share the stories you find and help them reach a wider audience.

How do you capture a story on the ground? What sort of gear do you take?

Before I go into the field, I do a lot of research about where I’m going. I try and get a sense of the issues playing out.

I also try to read a lot of the history of a place. I recently traveled to the Arctic, and before leaving, I read a fascinating book called Arctic Dreams by Barry Lopez, who spent two years traveling there in the ‘80s, a time when the Arctic was like another planet. I try to find voices like that. Anything that inspires me.

RELATED: How a single Instagram feed helped reframe a continent

On the ground, I just have my black notebook (I’m constantly scribbling). And I have my iPhone in my pocket all the time, ready to take portraits of the people I meet. I’m looking for anything that’ll help me remember the place. In the Arctic, I couldn’t write as much as I wanted to because my hands were so cold all the time. I’d take notes during the day and ask guys to repeat themselves, and put it all together in the warmth of the tent at night.

You lecture in non-fiction too. Do you have any tips for young travel writers out there?

One of the biggest things I remember from my teaching days was, in a lot of students, there’s this desire to be a Really Great Writer™. So they write the shit out of it. You know, they crank the dial right up to 11. They go all the way. And it’s too much. Their writing starts to crowd out the story.

Pianists explain this best. The music—or the story in our case—passes through you to get to everyone else. You’ve got to get out of the way so the music—the story—can blossom.

A lot of people come to college and they think they’re a good writer because their parents have probably been telling them for years they’re a good writer, but they’re not used to writing for a total stranger. One of my greatest writing professors told me, ‘You won’t be a great writer until you go out into the world and start to experience things.’ So some version of that is what I tell my kids. If they really want to do this, they should get out of here.

Why do you go where you go? And cover the stories you do?

It would be remiss of me not to admit to the allure of covering conflict. With Iraq, it was my generation that was fighting and picking up the pieces. I had friends who were in the military. I felt like it was the story of my generation, and I didn’t believe what my government was telling me. I wanted to see it for myself.

I was, like, 30 at the time, and sure there was a small part of me that thought, ‘Yeah this is gonna be cool’.

But I always feel like an asshole when I talk about this stuff. The danger isn’t why we do it. Yeah you get shot at sometimes. You get blown up. A polar bear chased me once. You’re not sure what’s going to happen next. I’m not unusual in that way—I’m not a conflict reporter. There are plenty of men and women who’ve done much crazier stuff than me.

Now that I’m older, I pick my destinations more carefully. Like Kurdistan. I admire the Kurds. Their landscape is so ancient, filled with history. The Kurds are people who, in my opinion, deserve their own homeland, but they’ve been denied it. There’s drama, there’s a sense of longing, there’s a deep past that goes back as far as you can possibly go. I think that’s an important story.

—-