Great Forest National Park hasn’t been declared by the Australian government yet, but the people are treating it like a park anyway. It might be the most brilliant plan yet to protect this old-growth forest.

Great Forest National Park hasn’t been declared by the Australian government yet, but the people are treating it like a park anyway. It might be the most brilliant plan yet to protect this old-growth forest.

What do you do if you want the government to create a national park, but it hasn’t signed the paperwork yet? If you’re Sarah Rees, Creative and Business Director for the Great Forest National Park, you might just start acting as if it is a national park. And you’ll get your community on board too, to start talking about it, teaching about it, and engaging with it as if it already exists.

Recently, Rees and the group working to establish Great Forest National Park in Victoria, Australia, published a guidebook titled, simply, Great Forest Park Guide. In the upper right corner of the cover, there’s an emblem for ‘Great Forest National Park’. Not the ‘proposed’ GFNP, or the ‘potential’ GFNP. Just the Great Forest National Park.

“I hate to say ‘fake it till you make it,’ because it actually exists,” Rees tells Adventure.com. “But it’s kind of, ‘craft it till we land it.’ Just keep imagining into it and what it could be.”

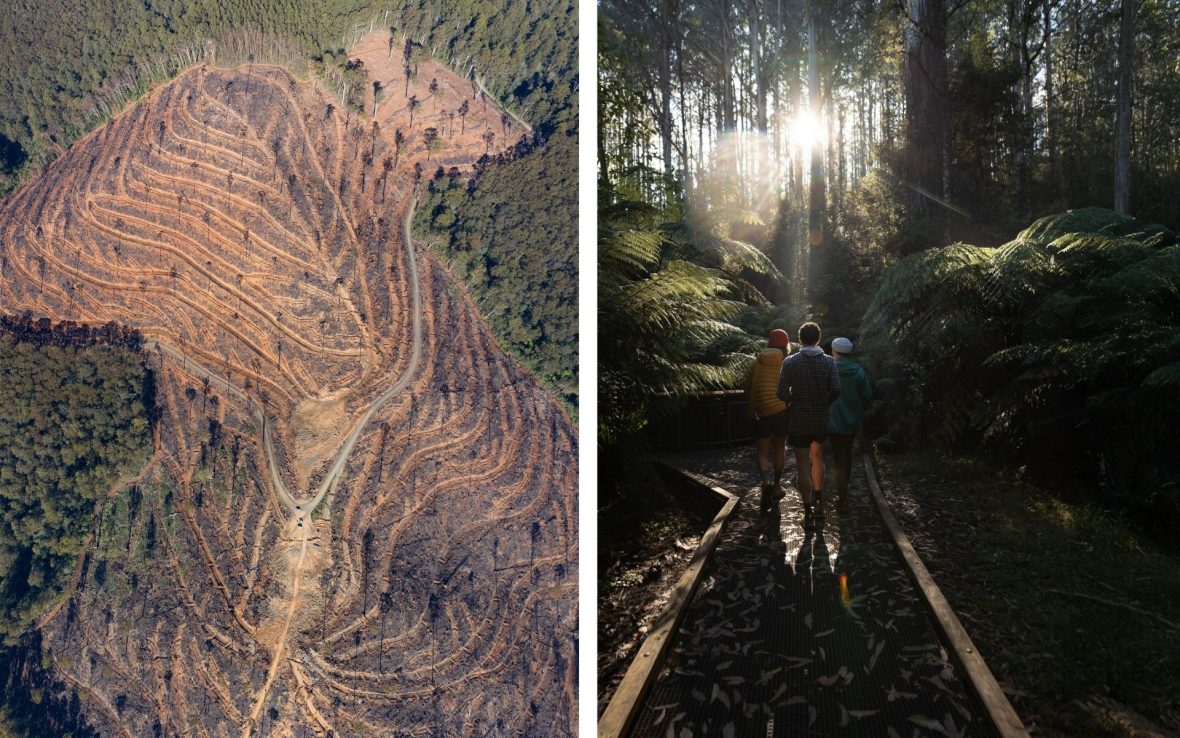

Rees has been working to protect this land for decades, ever since she laid eyes on a section of clearcut forest (also called ‘clearfell’) near her home in Marysville, Victoria, in 1999. She became a full-time activist a few months later. Finally, last year, the state put an end to the logging industry here, six years earlier than they planned to. A Supreme Court ruling found that VicForests, the state-owned logging agency, had failed to protect endangered species.

The park encompasses an area of about half a million hectares, or 2,000 square miles—a bit smaller than the state of Delaware. Roughly 80 percent of Victoria residents support the park, according to a survey conducted on behalf of the Wilderness Society and Victorian National Parks Association.

Aside from protecting the local environment and their drinking water, people here just need more access to nature, Rees says. Compared to Sydney, Melbourne residents have relatively little nature and protected green space within easy reach. GFNP would help to close that gap.

We just need them to say ‘yes, OK, we’ll take it. The investors are all lined up, ready to give, and the big banks are ready to assure it.”

- Sarah Rees

The guidebook includes maps, recommendations for hiking trails, GPS coordinates for the area’s most beautiful and awe-inspiring trees, and interviews with scientists, pro athletes, locals, and more. Even zoologist Jane Goodall weighed in to share her support.

The book is just the latest measure to manifest government recognition of the park. Rees has also worked with local schools to get teachers on board. Students learn the importance of protecting the forest and the endangered species that call it home, including the Leadbeater’s possum.

Rees hopes young people will see the value in landscapes, and learn to use data and mapping tools to critically analyze scientific studies. For example, they can weigh the merits of a park that would attract a projected 400,000 annual visitors, who would be expected to contribute roughly AUD$70 million (USD$45m) to the local economy and support at least 750 new jobs.

It would cost about AUD$224 million (USD$144m) to establish the park and create necessary infrastructure. The park’s supporters have already laid the groundwork for that, however, and Rees says investors are poised to fund every dollar within 48 hours. Her group has designed a ‘green bond’ the state government could issue to borrow funds at a lower interest rate and pay them back over 10 years.

“We just need them to say ‘yes, OK, we’ll take it,’” she says. “The investors are all lined up, ready to give, and the big banks are ready to assure it.”

If it sounds like the group is trying to talk the park into existence, by speaking about it as if it already exists so that people behave as if it’s already protected… you’re onto them. I asked Sarah about this, and she said that’s pretty much exactly what they’re doing.

“The secretary for the Department of Environment—I won’t name names—but he said when he arrived in Victoria, to take on this role, that he thought the park had already been declared,” Rees says. “By the way that it had received such a popular response, and by the innovative style of the campaign, he kind-of thought he was walking into a done deal, and that was quite a few years ago. So, I think he was quite surprised when he learned that, uh, no. It’s kind-of like we’re creating a virtual park.”

It’s wild enough that it just might work. And it’s not entirely unprecedented.

In England, groups like Right to Roam organize trespassing events to protest restrictions on hiking, camping, and swimming. Just this week, the Supreme Court ruled in favor of Dartmoor National Park to assert backpackers’ rights to ‘wild camp’ on private property within the park.

And in Colorado Springs, Colorado, over a decade ago, hikers defied ‘no trespassing’ signs on the Manitou Incline trail so flagrantly, that even Congress was moved to act in support of legalizing hiking access there.

If it works, protection for the new GFNP will give the forest time to heal and return to its former glory.

“[We’d have] visitation from all over the world coming to see some of the, historically, largest trees on the planet, and currently the largest flowering trees on the planet,” Rees says. “These are gonna be giants over time. And if protected and guarded from fire and other things, we’ll be rivaling [the US’s] redwoods.”

The guidebook is available now for AUD$30 (USD$19). Order it here.

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Kassondra Cloos is a travel journalist from Rhode Island living in London, and Adventure.com's news and gear writer. Her work focuses on slow travel, urban outdoor spaces and human-powered adventure. She has written about kayaking across Scotland, dog sledding in Sweden and road tripping around Mexico. Her latest work appears in The Guardian, Backpacker and Outside, and she is currently section-hiking the 2,795-mile England Coast Path.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: