Community, conservation, volcanoes and ancient traditions. When Indonesian writer Riza Annisa Anggraeni visited her ancestral homeland in North Sumatra, she ended up finding a blueprint for the ultimate Indonesian adventure.

Community, conservation, volcanoes and ancient traditions. When Indonesian writer Riza Annisa Anggraeni visited her ancestral homeland in North Sumatra, she ended up finding a blueprint for the ultimate Indonesian adventure.

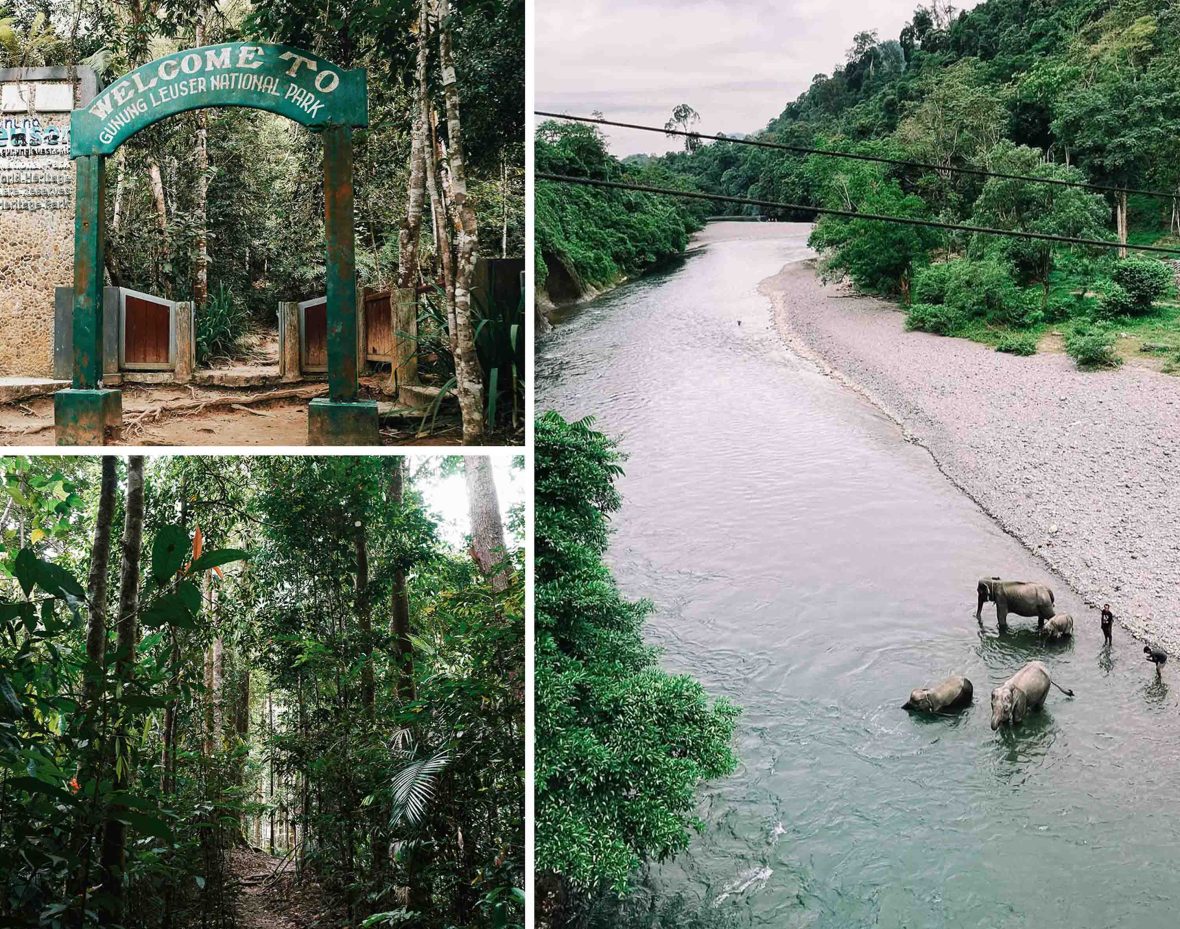

My entire body feels at peace as I dip my feet into the calm, warm, turquoise-green waters of the Batang Serangan River. I close my eyes, raise my head, and absorb the sounds. The faint pulse of life is audible: Hornbill wings flapping, the chirping of cicadas, and the cheerful sounds of elephants’ footsteps playing on the riverbank.

“Finally,” I whisper to myself. My journey had started in Medan, the capital of North Sumatra, a province of Sumatra, Indonesia’s third-largest island. I’d taken a three-hour bus to Binjai, hopped into an angkot (local minibus) to Batang Serangan then jumped on an ojek (motorcycle taxi) here to Tangkahan, a rural town on the edge of Gunung Leuser National Park (TNGL).

My mother is a native Batak (largest ethnic group of North Sumatra), and her clan is Hutabarat. She was born and raised here before her parents migrated to Java. I was raised in Bandung (West Java), and this trip marks my first exploration of my ancestral land.

Gunung Leuser National Park (TNGL) is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, part of The Tropical Rainforest Heritage of North Sumatra and a megadiverse rainforest area made up of three key areas: TNGL, Kerinci Seblat (West Sumatra), and Bukit Barisan Selatan (South Sumatra).

A global priority area for conservation, it’s home to Sumatran orangutans, Sumatran tigers, Asian elephants, abundant birdlife such as hornbills and kingfishers, and distinctive rainforest flora, from towering dipterocarps to the rare Rafflesia (a rare species of Rafflesia hasseltii was re-discovered just under a month ago in West Sumatra).

“We used to cut the trees, now we protect them. The elephants we once feared as pests are now our friends, helping us guard the forest.”

- Pak Aman, guide and mahout

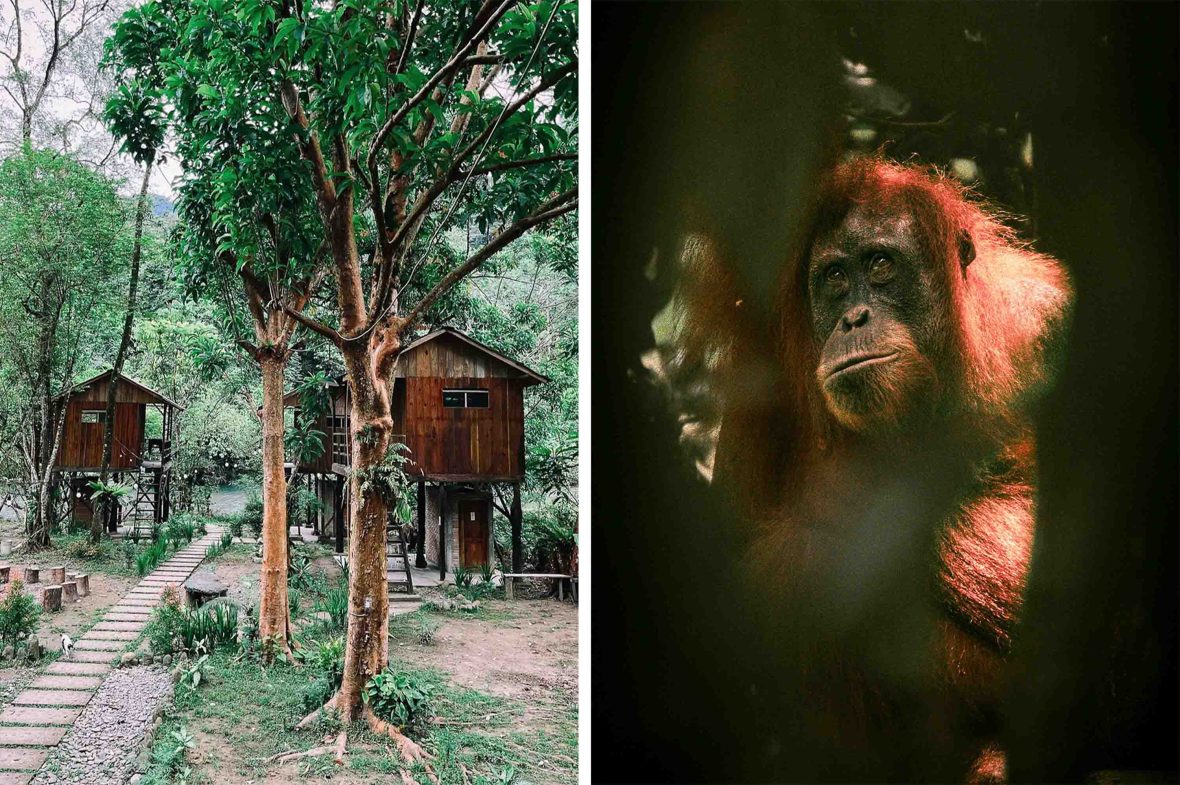

Tangkahan is, by tourism standards, undeveloped. There are no luxury resorts; only simple wooden guesthouses managed by the local community, perched along the river. I stayed in a simple stilted cabin with an outdoor hammock overlooking the water, costing 150,000 rupiah (USD$9) per night, enjoying the scent of damp earth and woodsmoke. More comfortable eco-lodges, priced between 350,000 and 500,000 rupiah (USD$20-30), offer private bathrooms and small balconies. Tourism here only started up in the early 2000s; its charm lies in its rustic, community-run atmosphere.

The village’s transformation was born from devastating human-wildlife conflict. Local villagers decided to act when they found their crops destroyed by wild elephants, resulting in elephants being maimed or killed by the local community in retaliation. This situation was particularly pronounced here, because Tangkahan was a hub for illegal logging which drove the elephants into town.

In April 2001, the community partnered with NGOs such as the Tangkahan Tourism Institution (LPT), a local community initiative, to establish the Conservation Response Unit (CRU), which now employs former illegal loggers as guides. Today, the CRU employs roughly two dozen people and several rescued elephants to patrol the forests, protecting the borders of the national park from illegal activity.

It’s in front of the Tangkahan gate, the entrance to the local community, where I join one of the local mahouts, Pak Aman, on a wildlife trek. At 40 years old, Aman is one of the youngest mahouts here after he shifted from being an illegal logger to a conservationist some 20 years ago. “By understanding our relationship with the elephants and other animals, our lives are more peaceful and sufficient,” he tells me.

I follow him through the wild, twisting trails of the humid rainforest, where the roots of giant fig trees sprawl across the damp earth. “These trees protect everything, from Sumatran tigers to Rafflesia hasseltii, the rare brick-red parasitic flower,” he tells me. The air smells of moss and wild ginger, and he shows me the towering Meranti (genus Shorea) and Damar (agathis) tree.

As a hornbill soars above the emerald canopy, Aman smiles. “We used to cut the trees, now we protect them,” he says. “The elephants we once feared as pests are now our friends, helping us guard the forest.”

Before long, we arrive in an area close to the elephants. Aman calls me over. Even from a distance, I can feel and hear the warm, heavy rush of their breath. I feel a deep urge to protect these elephants and understand why mahouts like Aman make it their mission to take care of them.

While I’m not ready to leave the rainforest, my next stop beckons: Danau Toba (Lake Toba). I’d heard many describe Danau Toba as a fragment of heaven, and I wanted to see it with my own eyes. In North Sumatra’s volcanic heart, it’s the world’s largest crater lake. Surrounded by pine forests and steep volcanic cliffs, its surface stretches for nearly 100 kilometers (62 miles), shimmering beneath the afternoon sun.

Four hours into the drive, I catch my first glimpse of the lake in the distance, almost mistaking it for the ocean. At an elevation ranging between 3,280 and 5,250 feet (1,000 and 1,600 meters), Danau Toba has fertile volcanic soil and a tropical climate ideal for coffee cultivation. Coffee farming is deeply rooted in the Batak way of life and is traditionally intercropped with other plants like chili and corn, ensuring biodiversity and soil health.

As the mist lifts, the deep blue surface of the lake stretches out in perfect stillness, reflecting the green cliffs. The cold mountain wind carries the scent of pine, the beauty of the moment instantly silencing my travel-worn fatigue.

“Instead of staying in those fancy hotels around Samosir, it’s better here. Those luxury hotels only make the investors richer. But if you visitors stay in local homestays, you help us prosper.”

- Ibu Tere, homestay host, Tomok village

Borne of an ancient volcanic eruption some 74,000 years ago, this giant lake holds ancestral tales of the Batak people, with stories of creation, spirits, and kinship tied to the surrounding mountains and forests. The most famous of these is the legend of the poor farmer Toba, who broke his promise not to reveal his wife’s origin as a giant fish. As a result of his betrayal, she transformed back into a fish and the earth erupted in a massive flood, creating the lake. The hill where their son, Samosir, took refuge became the island at its center.

Samosir Island is right in the middle of Danau Toba. Before I explore, I stop for lunch at Tombur Orangta, a restaurant a couple of kilometers from the ferry port, and tuck into a dish of Ikan Tombur (Sambal Na Tinombur), typically made with fresh Nile tilapia or carp from the lake. The fish is either grilled or roasted and served with a fresh, spicy, and sour Batak chili sauce, rich in spices and andaliman leaves. Before leaving, I order a Siborongborong Coffee, a sweet-and-spicy single-origin Arabica coffee characteristic of North Sumatra, grown at an altitude of 4,920 feet (1,500 meters) above sea level.

My goal for the rest of the day is simple: To visit Tomok, a traditional village. Tomok sits peacefully on Samosir Island, right in the heart of the lake. To get there, I just need to take a short car ferry from Parapat, the main gateway to the lake. The trip only takes about 15 minutes, but the views are special; a carpet of calm blue water stretching as far as the eye can see, framed by green hills that seem to touch the sky.

As soon as the ferry docks on Samosir Island, I head straight for Tomok. The road is quiet, lined with tall trees and traditional Batak houses, each with its own charm. I feel a sense of peace.

The large stones used for the Batak kings’ court are still in place in the village, and the traditional houses stand strong, adorned with red, white, and black gorga carvings; swirling patterns of flora, animals, and ancestral motifs said to represent harmony between the human world, the natural world, and the realm of spirits.

“Horas!” says Ibu Tere, the kind, local woman in her 50s who owns the homestay where I’m staying. This typical Batak greeting for hello and goodbye is also one that expresses gratitude and good health. She’s clenching her right hand upwards, full of energy. “Instead of staying in those fancy hotels around Samosir, it’s better here,” she tells me. “Those luxury hotels only make the investors richer. But if you visitors stay in local homestays, you help us prosper.”

Ibu Tere’s house is made of teak wood with high ceilings, and I settle into my room until Ibu Tere calls me downstairs to taste ‘Mi Gomak’, a traditional Batak noodle dish in a yellow coconut-milk broth.

The noodles are thick and straight, soft yet pleasantly chewy, and its flavor comes from the andaliman spice, or ‘Batak pepper,’ a fresh, spicy pepper, slightly bitter or numbing feel on the tongue, similar to Sichuan pepper. Sometimes, kecombrang flower (kincung) is also added for its distinctive aroma. It reminds me of my mother’s cooking—and eating with Ibu Tere makes me feel I’m not so far from home. The day turns to dusk. As we eat dinner, we hear the sound of the hasapi, the traditional lute of the Batak Toba people, played by Ibu Tere’s neighbors’ children.

North Sumatra, with its volcanoes, ancient traditions, and people rooted in conservation, has not just been a holiday destination for me, but a blueprint for understanding myself. Though I grew up in Bandung, this first true visit to my ancestral land felt like a revelation, a sense of coming home to a place I never realized I had lost. The traditions, the food, the warmth and the rhythm of nature; it all felt familiar.

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Riza Annisa Anggraeni is an Indonesian mountaineer, journalist, and independent researcher whose work explores rural and mountain landscapes and communities. Through conscious travel and storytelling, she seeks to reframe travel as a grounded relationship with the Earth, offering an alternative to extractive travel narratives and inviting readers into slower, locally rooted journeys across the Indonesian archipelago.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: