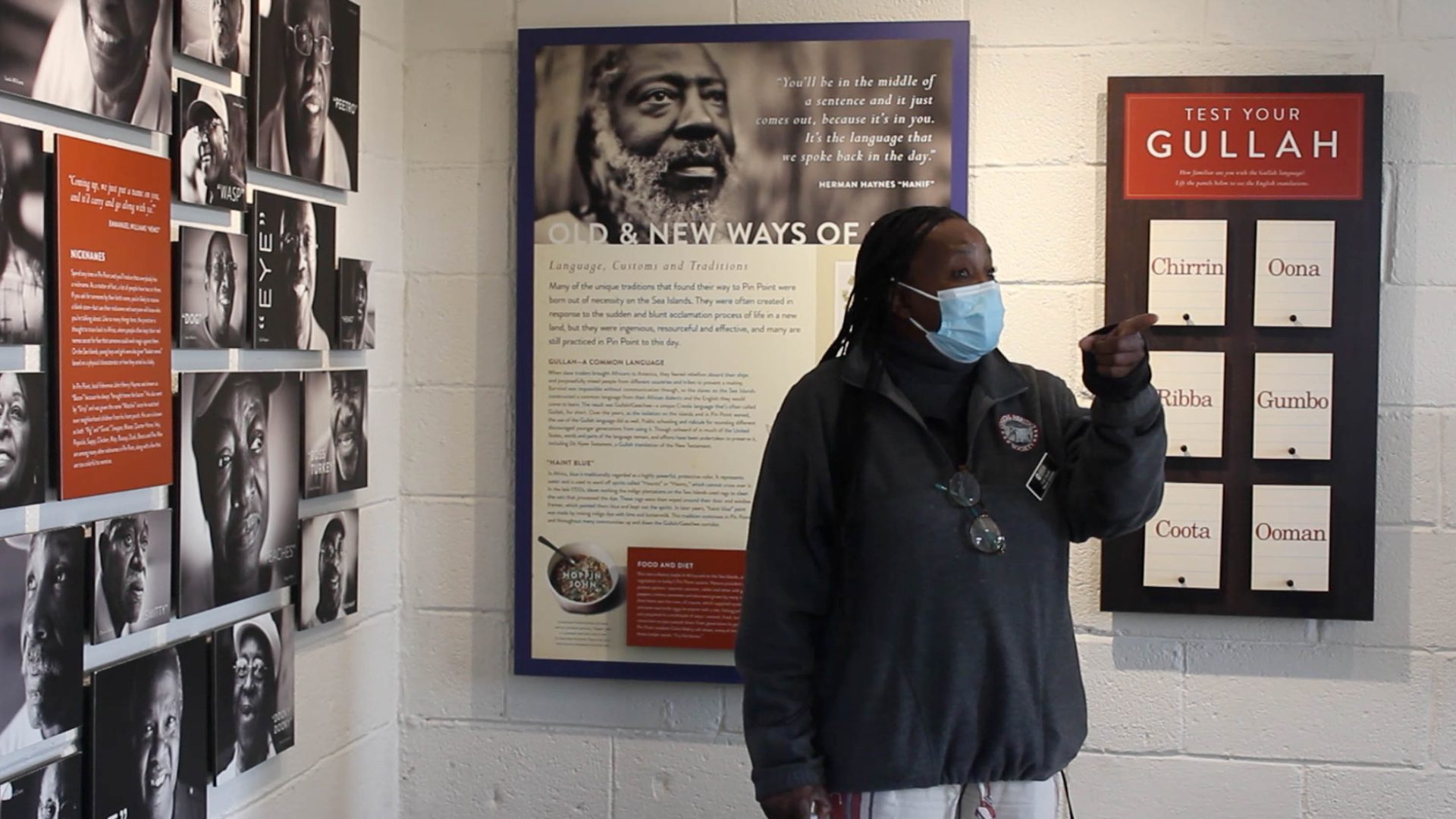

As we step inside the Praise House, our local guide, an elderly bespectacled man, underscores the relevance of these houses, post-slavery. We sit on wooden benches as he teaches us how to speak Gullah. “Gullah isn’t a made-up language, it’s real,” he says, emphatically. “These Praise Houses were used for baptisms, meetings, settling disputes. It’s important to know where you come from.”

This shack is a reminder of the dual nature of the Gullah Geechee. Praise Houses are both a powerful symbol of rebellion against slaveowners, and their religion, and vital sites of rest and recovery for the Gullah Geechee people, who were forced to toil in seas and rivers for generations.

Their geographic isolation has helped preserve the Gullah Geechee’s distinct culture. But many communities today are threatened by rising tides, complex land-owning laws and private development. The National Trust for Historic Preservation placed the Gullah Geechee Coast on its list of most threatened places in 2004, due to the rising tides. Queen Quet, a native of St. Helena Island and head of state for the Gullah Geechee community, spoke at Congress in 2019 to express how fishing prospects were dwindling due to rapid increases in water temperatures.