Editor’s note: This article was published before the coronavirus pandemic, and may not reflect the current situation on the ground.

For many, telling the story of the Great Barrier Reef is as important as the science of saving it. Shaney Hudson looks at the connections being forged by traditional owners, tourism corporations and scientists as they fight for the future of this global icon.

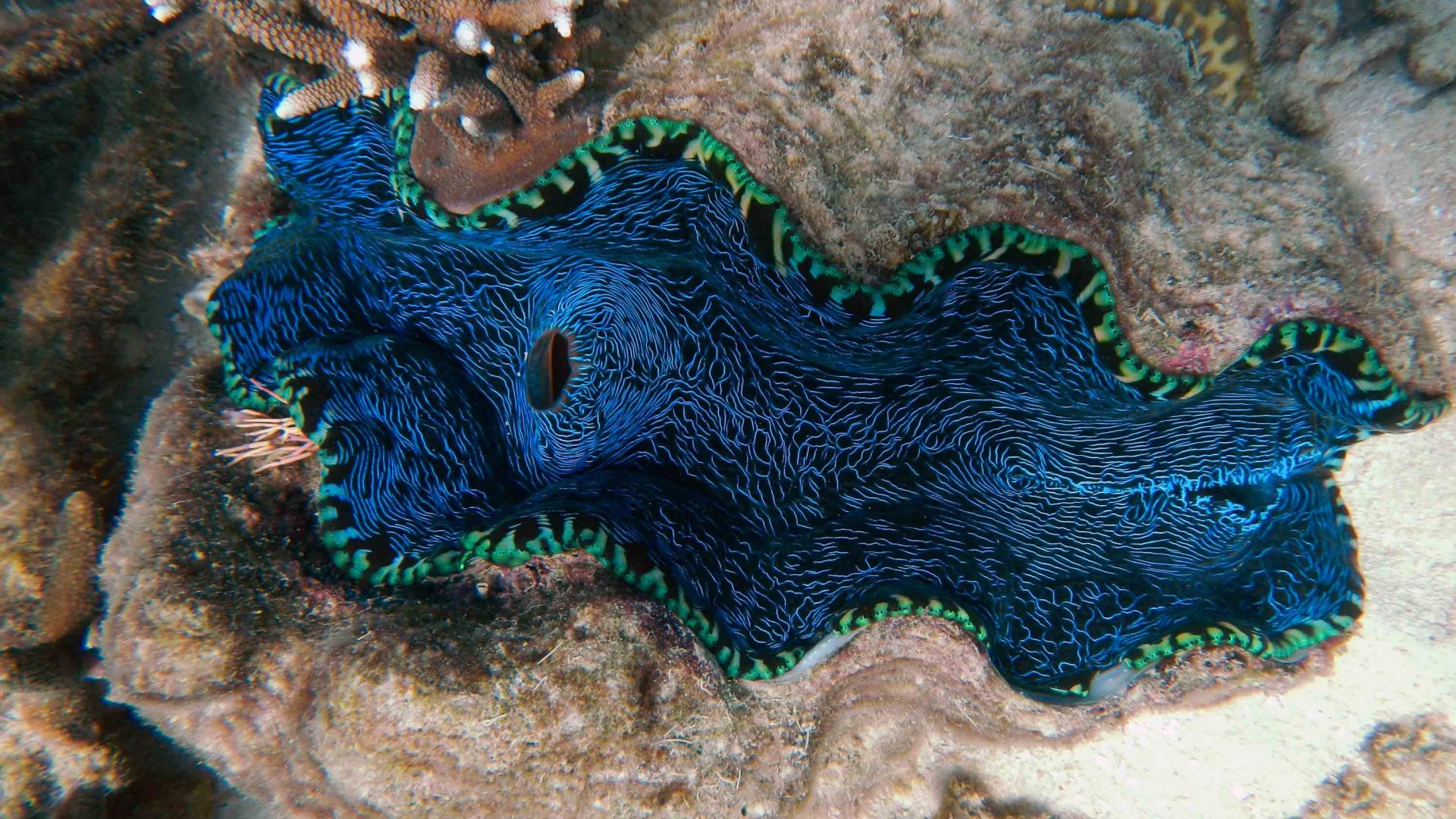

I’m floating face-down in the water. There’s a marine biologist bobbing to my left, an Indigenous ranger treading water to my right, and below us, the spectacular underwater world of the Great Barrier Reef. It’s even better than it looks in the oversaturated brochures, and spine-tingling to see with my own eyes.

It’s a

relief. After years of media hype claiming the reef was dead, or dying, I’ve found

coral gardens of pastel blue staghorns and elegant crimson fans, giant clams

that flinch when we swim overhead, and a hive of fish—some cowardly, all

colorful—darting in and around an ancient underwater ecosystem.

While the

marine biologist explains the science, our sea ranger talks us through the Indigenous

value of what we’re seeing: Giant sea cucumbers whose slimy secretion was used

for sunscreen, coral used for ceremonial scarring, and the importance of this Sea Country to her people.

Earlier in the day, we’d seen the big reef attractions during our first stop at Moore Reef—docile sharks, swimming sea turtles, and photogenic clown fish that seemed to smile for the underwater camera. But it’s during our snorkel safari of Flynn Reef that we see the most important Dreamtime (the foundation of Aboriginal spiritual belief) totem to the local Indigenous tribes: The black stingray. Spotting it below, I signal to the group.

RELATED: Your guide to the future of sustainable travel

“Oh great, guys. A stingray is really good luck!” our sea ranger, Lori Tim Ghee says, beaming.

“Hang on …” She pauses. “Was it a black or a blue-spotted one?”

“A blue-spotted one,” I reply.

“Nah,” she says, grinning. “That’s not good luck—that’s just a stingray”.

“It’s good to see Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander youth host the world,” says Indigenous elder Darryl Murgha, a senior ranger with the Gunggandji Aboriginal Corporation, who’s accompanying us on the tour.

As the Great Barrier Reef battles the impact of the climate emergency, there’s an increasing focus on collaboration: Those with cultural ties are linking up with commercial enterprise, while tourism operators are working with scientists to safeguard the reef.

“It’s a new product, a unique product, and it’s a great bridge builder,” says Trevor Tim, Indigenous operations manager of Experience Co. “This operation is the first of its kind on the reef, where a private company has opened up doors to create a space, a business entity, with Indigenous culture at the table and involved.”

At Moore Reef, we tie up near Marine World. The floating pontoon is used for tourism during the day, but just four nights earlier, it was a base for scientists to monitor what turned out to be one of the most successful coral spawning events in years.

“I know people often worry about development and the impact of tourism, but honestly, tourism is a good thing for the Great Barrier Reef,” says David Wachenfeld, chief scientist of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority. “Both in terms of what the visitor experience, but also how the industry works with us in partnership.”

RELATED: Not visiting Uluru because of the climbing ban? You’re missing the point

Currently, 80 per cent of tourism on the reef occurs in less than 10 per cent of the area of the Marine Park. Additionally, the compulsory environmental management fee which generates between AUS$10-15 million a year, goes back into the conservation of the Reef. Tourism isn’t the problem, but getting visitors to understand the size and complexity of the issues impacting the reef is.

With this in mind, the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, the Association of Marine Park Tourism Operators, and Tourism and Events Queensland created the Master Reef Guide program, a tourism plan that puts a huge focus on guides interpreting and communicating the scientific data in a meaningful way to visitors.

From cultural sea rangers to specialized marine biologists, the aim is to put the story of the reef in context and hope that if people see it, and learn about it, they’ll want to save it. But despite all the good news, the challenges facing the reef aren’t insignificant.

“I think we need to be really clear that although the Great Barrier Reef is an amazing place, it has been damaged by climate change and climate change is getting worse”, says Wachenfeld. “Globally, we have not done anywhere near enough yet to get it under control. It’s a global problem. It needs a global solution. I know that when people come and see the Great Barrier Reef, they fall in love with it. And having fallen in love with it, they immediately want to know what they can do to protect it.”

Returning to Cairns from the outer reef, I sit and yarn with Darryl Murgha about Sea Country, the young Indigenous crew, his desire for people to understand his culture, and his hopes for the future of the reef. “We need to protect it,” he says simply. “I don’t want to show my children what a dugong or turtle used to look like out of a book, you know?”

—