At 52 feet tall (16 meters)—taller even than LA’s Hollywood sign—Fiji’s BULA Reef, designed to combat coral bleaching, just celebrated its first birthday. We ask the scientists behind the innovative underwater project for a reef restoration update.

At 52 feet tall (16 meters)—taller even than LA’s Hollywood sign—Fiji’s BULA Reef, designed to combat coral bleaching, just celebrated its first birthday. We ask the scientists behind the innovative underwater project for a reef restoration update.

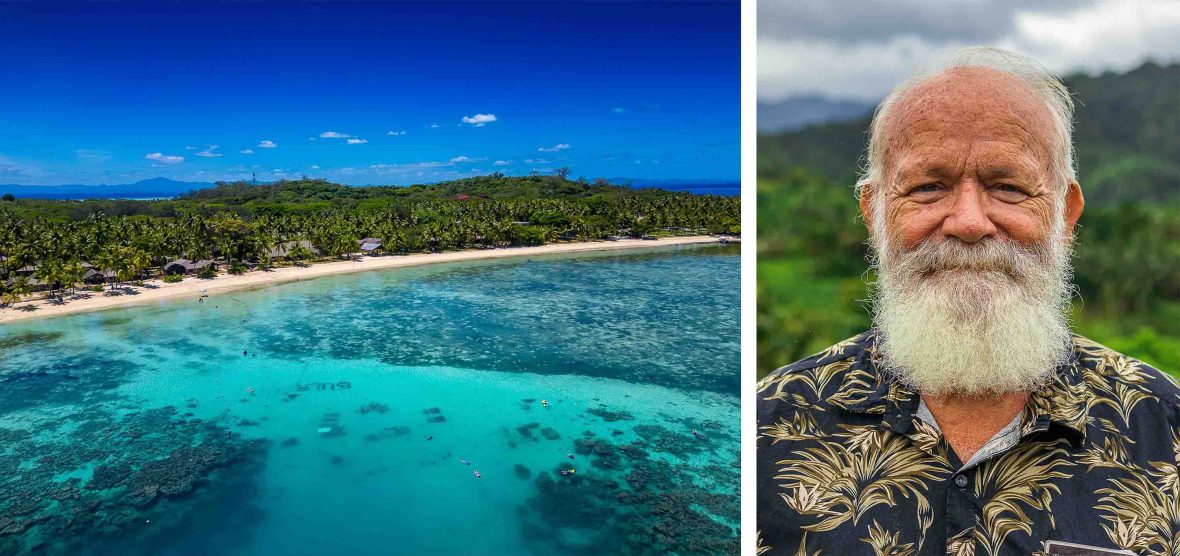

With a bushy white beard and a glint of mischief in his ocean-blue eyes, Dr. Austin Bowden-Kerby could easily be mistaken for Santa Claus. Except for the fact he’s 7,500 miles (12,000 kilometers) off-course and six months too early. Indeed, if this marine scientist’s ambitions to save the South Pacific’s reefs are realized, this may be the greatest gift this region, and the warming ocean waters the world over, could ever receive.

Onboard a boat to visit BULA Reef, Bowden-Kerby is less Saint Nick and more pirate, clad in a blue bandana, a hint of a missing middle tooth, and armed with all the grit and passion for which he is renowned in the South Pacific region.

It is out here, off Malolo Lailai in the Mamanuca Islands—off the west coast of Fiji’s main island, Viti Levu—that Bowden-Kerby and a small team of Fijian marine biologists are waging mutiny on climate change, and the crown-of-thorns starfish, which preys on coral polyps and decimates reefs. BULA Reef is a nursery designed to rescue thousands of coral populations and plant heat-resistant colonies.

Fiji-based Bowden-Kerby, who runs the local NGO Corals for Conservation (C4C), partnered with Plantation Island Resort to build the giant underwater reef. 147 feet long (45 meters) and spelling out ‘BULA’, the Fijian word for ‘hello’ or ‘welcome’.

It’s the largest word ever written under the ocean, and the result of a 10-month project which came to fruition in June 2024 after more than a thousand colonies of rescued heat-resistant corals were transplanted to this elevated wire mesh structure.

“We try to give these corals a second chance by placing them at the BULA Reef. They are doing perfect. They’ve never looked better.”

- Luisa Nadavobalavu, marine biologist

This followed six years of water-testing by dozens of local and international marine biologists and volunteers at various sites to determine the ultimate temperature in which to place the reef. It was on World Oceans Day last year that local Fijian chiefs from the Malolo Islands inaugurated BULA Reef, which is UN-endorsed.

“This is the Goldilocks reef… the coral is not too hot in the middle reef,” says Bowden-Kerby. “Over there, on the outer reef, that’s the Papa Bear reef where it’s too cool. While on the other side of us is the Mama Bear reef where the coral is too hot.”

One year later, on a windy day out on the ocean, the 70-year-old scientist describes removing the “hot pocket of corals” from West Nuku Reef, about half a mile from the new BULA Reef site, as a “globally significant contribution.”

“We were able to save close to 2,000 colonies of corals that survived without bleaching at temperatures which went up to 95 degrees and above,” he says, “and this means it’s a huge breakthrough in keeping corals alive. Where we took the corals from, the remaining corals have since died. The corals got to 100 degrees in the shallows and where we put them in, they were only 91 degrees, so they were fine.”

These marine scientists are confident they’ve unlocked a new way of keeping alive corals pre-adapted to climate change, which could have significant implications for other reefs around the world.

Despite its impressive size from the air, it’s a sanguine snorkel as I trace the curves of the B before contorting my body into the U, and tracing the line of the long L, and finally twisting and tumbling over the A. BULA—I repeat the greeting out loud through my snorkel tube.

Through my mask, it’s clear from the kaleidoscope of curious fish darting in and out of the pink, purple and green coral that this reef is not only surviving but thriving, despite the relatively warm water lapping my body.

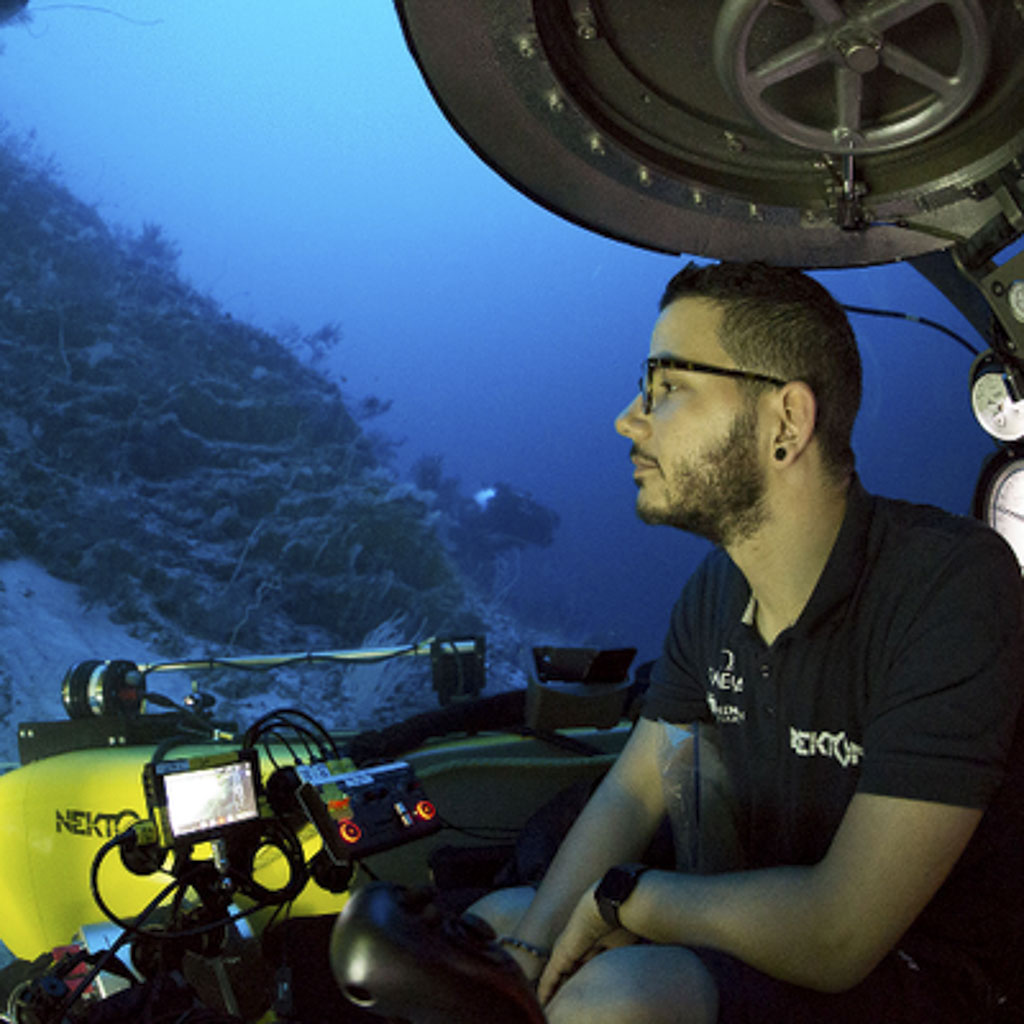

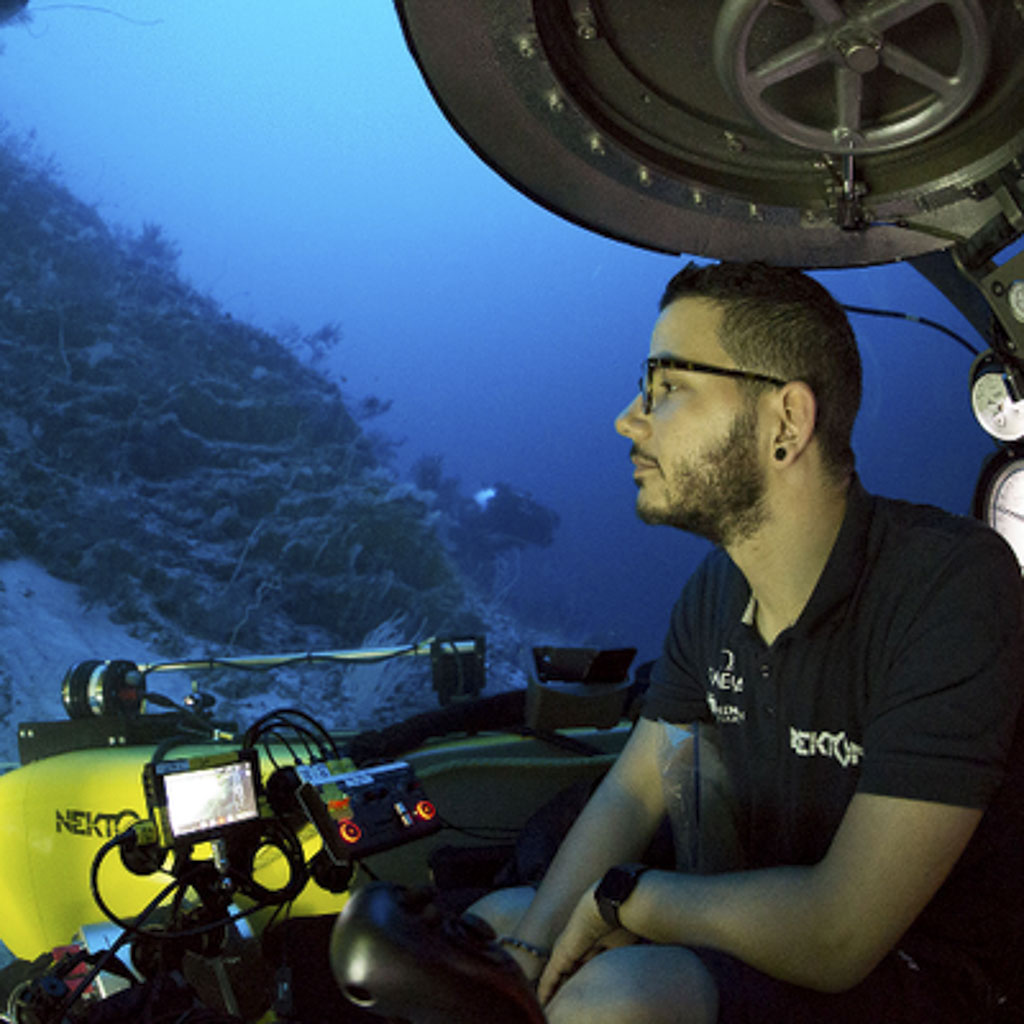

Plantation Island Resort marine biologist Luisa Nadavobalavu, who snorkels and works on the reef every day as part of a team of four, was involved in initially building the underwater structure and removing algae. “I worked on getting the best corals for the structure,” she tells me. “They are from different areas around the reef. We have some hot pockets in the area with higher water temperature and these corals have learned to adapt to the warmer temperatures.”

Nadavobalavu and the team have also replanted corals that had been struggling, either due to a proliferation of crown-of-thorns starfish or uprooted after cyclones or storm surges. “We try to give these corals a second chance by placing them at the BULA Reef,” she says. “They are doing perfect. They’ve never looked better. They are mostly slow-growing coral varieties.”

Nadavobalavu admits there were initial challenges with installing the reef—including hammering the sustainable mesh wire to which the underwater letters are attached–and difficulty in attracting fish. “We had to struggle a bit getting fish onto BULA Reef because the structure was so big,” she says, “but we’ve managed to create some fish spots and they are doing amazing at cleaning the structure. They love their new home.”

“BULA is a Fijian word used for ‘hello’ and it also means ‘life’. It is about life in the sea, life in the communities and life in the tourism industry. What makes this project unique is that for the first time in history, we have found a ray of light that leads us into the future.”

- Dr. Austin Bowden-Kerby

While it’s still too early for the scientists to start collecting data on species on this new reef, Nadavobalavu says the rainbow-colored parrot fish and small blue and yellow damsel fish have been particularly attracted to the site. The bright coral is visible even on a gray day.

“We are very happy to see the coral thriving and the fish doing their homemaking so they are jumping from coral to coral, trying to make a home,” she says. “In another year, I wouldn’t expect to see the mesh structures which will be covered in corals and much more fish. It’s going to be a happy reef.”

I snorkel a short swim away back to Bowden-Kerby who is hovering above the main Great Sea Reef—this is where the flourishing coral from the BULA Reef nursery is eventually transplanted once its deemed healthy enough to survive on its own. Bowden-Kerby is intent on smashing a crown-of-thorns starfish—which looks part-Australian echidna and part-tumbleweed—with old coral, to destroy his underwater nemesis.

“This Barrier Reef is like a honeymoon cottage for corals to have babies,” he tells me. “We are going to be pumping out millions of baby corals from this nursery and they are heat-adapted.” Bowden-Kerby also refers to “seduction by scuba tanks”—referring to travelers who dive the world’s reefs but don’t focus on the science or threats behind these underwater habitats.

Bowden-Kerby believes humans need to take responsibility for the planet’s warming oceans and intervene in a positive and proactive way to ensure corals and fish survive. “It’s not like we won’t have any reefs in the future, but they are shifting into an alternate state,” he says. “There will only be one or two kinds of reefs and not much diversity. I’m trying to wake people up.”

“BULA is a Fijian word used for ‘hello’ and it also means ‘life’. It is about life in the sea, life in the communities and life in the tourism industry. What makes this project unique is that for the first time in history, we have found a ray of light that leads us into the future.”

On my final two days at Plantation Island Resort I am reminded of the fragility and beauty of this part of the planet. On a dolphin safari, a 25-minute boat ride away, I witness a pod of half a dozen spinner dolphins frolic in the wake of the boat, before snorkeling the still healthy Nuku Reef.

Another day, on mid-tide, I wade 65 feet (20 meters) from the shoreline between Plantation Island Resort and its adults-only sister property Lomani Island Resort & Spa to snorkel its quirky Underwater Museum.

As I glide over underwater structures such as sunken golf carts, bicycles, and tables and chairs replete with crockery and cutlery, it strikes me as a fitting metaphor. All of us who care are taking a seat at the climate change table, ensuring corals and fish are protected so we can help guarantee the survival of vulnerable communities whose livelihoods are so dependent on the ocean.

**

The writer traveled as a guest of Plantation Island Resort, the custodians of BULA Reef; they run once-weekly protected guided snorkeling tours to the site.

*

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Christine Retschlag is a multiple award-winning Australian travel journalist with 34 years of experience, who is working and living in Australia, Hong Kong, London and Singapore. At home, you’ll find her on the back deck of her Queenslander cottage with possums, kookaburras and the resident carpet python who makes the occasional cameo appearance.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: