For her ongoing series, The Unknown River, photographer Tanya Houghton has collaborated with local Indigenous women, park rangers, scientists and thru-hikers to pay homage to the Colorado River’s female legacy and natural systems.

For her ongoing series, The Unknown River, photographer Tanya Houghton has collaborated with local Indigenous women, park rangers, scientists and thru-hikers to pay homage to the Colorado River’s female legacy and natural systems.

Tanya Houghton focuses her photographic career on the intersection of wild landscapes and human connection. Fascinated by how the spirituality of the natural world leaves an imprint on those who occupy it, this intrigue has taken the London-based photographer from Indigenous communities in the Australian desert to traditional healers in the Panamanian jungle.

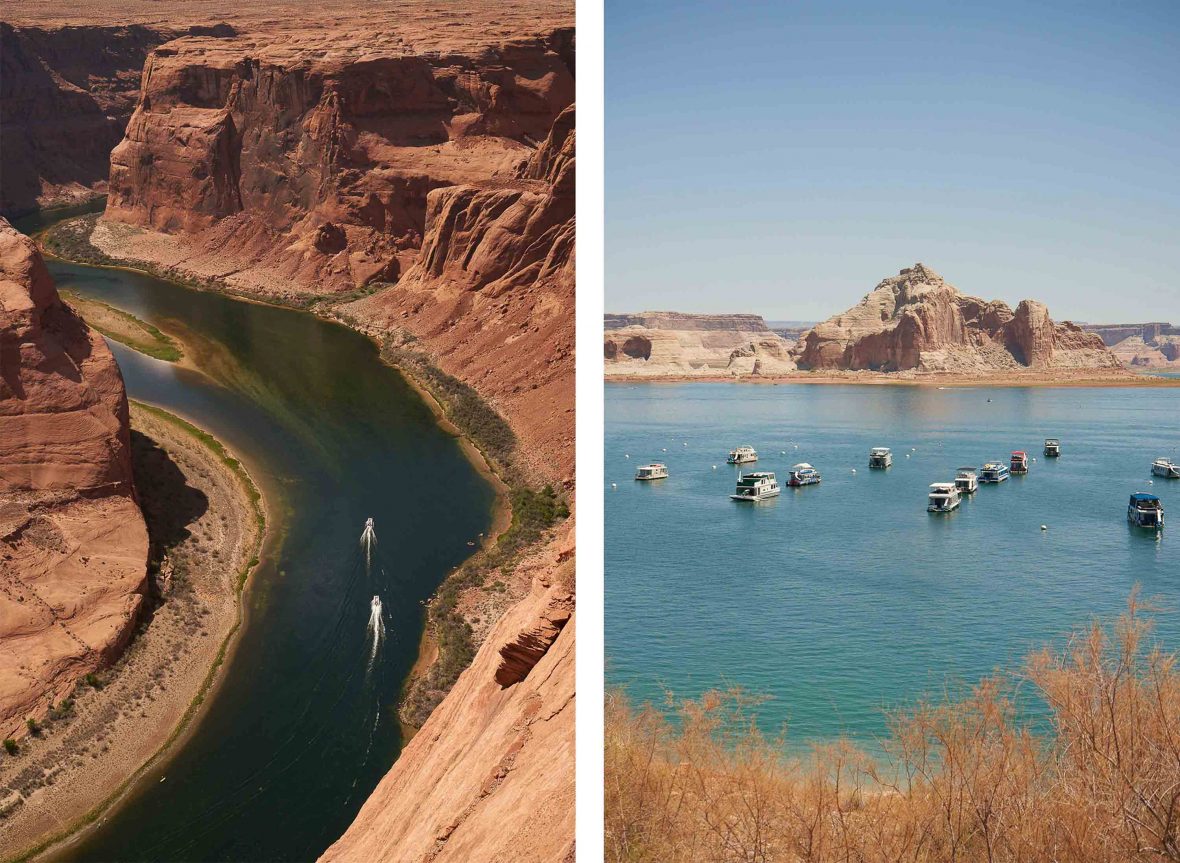

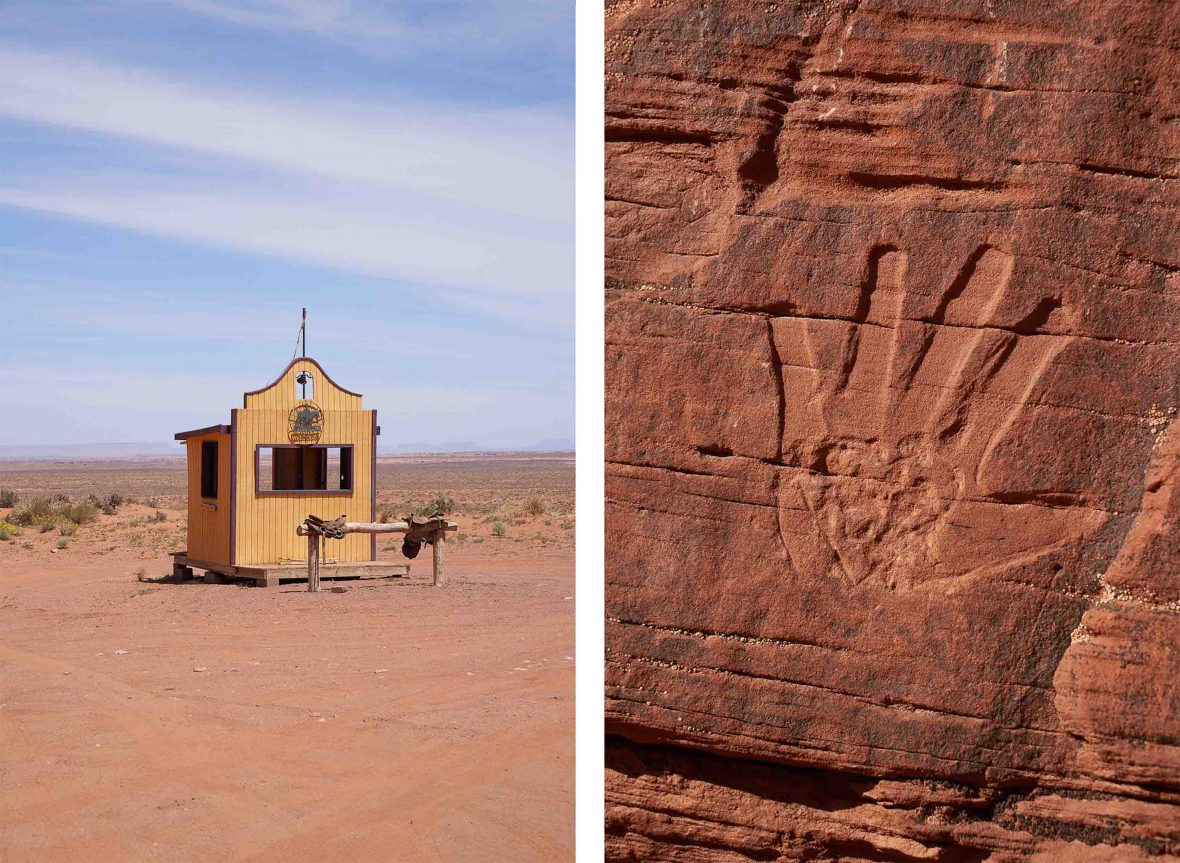

During a 2019 road trip across America from Los Angeles to Boston, Tanya became enamored by the immense Colorado River. For much of the journey, she camped along the 2,300-kilometer riverfront, capturing the canyons that pierce the landscape and surrounding towns. In these communities, she learned how history and politics have shaped a harsh terrain that “cuts through time.”

“The river is the backbone of America, an intricate water system that has been carving its way through the earth’s crust for billions of years,” says Houghton. “To see it up close allows you to look back in time.”

As a starting point for The Unknown River, Houghton delved into the journals of John Wesley Powell—a 19th-century explorer and geologist who led the first recorded passage of white men through the Grand Canyon in 1869. Later, as director of the US Geological Survey, the issues he raised about relying on the Colorado River for water access continue to plague the American West today.

“I’m interested in gathering and shining light on the women’s stories from this place, using the Colorado River as the stage and allowing the stories to be told in the women’s own words.”

- Tanya Houghton

Drought and water shortages are only worsening in major cities like Las Vegas, Phoenix and Los Angeles, as the Colorado River struggles to provide enough drinking water and irrigation for 40 million people and 5.5 million acres of agricultural land. Powell publicly fought against the pseudoscientific concept “rain follows the plough”—a once broadly accepted belief that crops attract rain, even in the most inhospitable environments.

He also appeared before the US Senate in 1890 to argue against irrigating the West’s desolate landscape. Despite presenting an emphatic case that the country’s natural resources required a more strategic approach, his position ultimately lost to economic interests as the Colorado River was dammed and diverted for drinking water, irrigation and, later, hydroelectricity.

“At present, we are entering a new phase of climate change,” says Houghton. “The levels of Lake Powell are at their lowest ever recorded and Glen Canyon is revealing hidden treasures that were once lost to flooding caused by the building of Glen Canyon Dam.”

Alongside Powell’s work, Houghton also discovered inspiration in the experiences of river runner Buzz Holmstrom and backpacking pioneer Colin Fletcher. However, as a female photographer who spends much of her time roaming remote locations, the transformative accounts of women like singer-activist Katie Lee and rafter Patricia McCairen from within the Colorado River’s “male-dominated sphere” were especially insightful.

“This is my first body of work that explores gender and the landscape—or eco-feminism,” says Houghton. “I’m interested in gathering and shining light on the women’s stories from this place, using the Colorado River as the stage and allowing the stories to be told in the women’s own words.”

Some of Houghton’s collaborators include the first non-Indigenous American woman to solo raft the Colorado River, the Hualapai River Runners’ only female boat runner, and Hopi women raised inside the Grand Canyon National Park. The role of “spiritual ecology” is a consistent theme throughout their stories, with Houghton explaining how people frequently describe the Colorado River as a holy place.

“It’s the sense of adventure, a record of a journey, the knowledge that there is something bigger than you that resonates with me.”

- Tanya Houghton

“There are moments when we are in nature where we experience the sublime, wonder, curiosity,” says Houghton. “The spiritual connection to the river, the land and its people has been present throughout the history of humankind. Simply look at the traditional land custodians—the 11 tribes of the Grand Canyon Plateau.”

With this sacred connection promoting an egalitarian relationship between humans and the landscape, the American West’s problematic reliance on the Colorado River for water supply is a telling reminder that our existence depends on the natural world. Houghton is now looking to add to her narrative, with the next chapter reflecting her personal experiences on the riverfront.

“It’s the sense of adventure, a record of a journey, the knowledge that there is something bigger than you that resonates with me,” says Houghton. “This will be the first time I have physically featured myself in my work. I’m not sure yet where the river will take me—that’s kind-of the beauty of it.”

***

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions publication, and we are working to reduce our carbon emissions where possible. Emissions generated by the movements of our staff and contributors are carbon offset through our parent company, Intrepid. You can visit our sustainability page and read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information. While we take our commitment to people and planet seriously, we acknowledge that we still have plenty of work to do, and we welcome all feedback and suggestions from our readers. You can contact us any time at hello@adventure.com. Please allow up to one week for a response.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: