As bushfires ravaged his homeland, Australian adventurer and environmentalist Huw Kingston was thousands of miles away. Having returned early to his community as the fire approached, he reflects on what the fires mean for the world, now and in the future.

Today, late January, is another day where smoke

wafts into the house and stings my eyes. Another night just passed with the sky

glowing red from fires burning in the deep gullies below Bundanoon, my little

town in New South Wales. It has been like this for weeks now. The sound of

sirens, the sight and smell of smoke.

This is our summer.

In the months before this summer had even begun, millions of hectares in northern New South Wales and southern Queensland had burnt, and millions of animals had been killed. Dozens of properties had been destroyed by October, nearly 500 by November. Lives were tragically lost.

During those weeks before I flew to Europe in early December, the beast had moved south, closer to home, but still a distance away. I felt a little nervous to be leaving. Our prime minister, a man who had once carried a lump of coal into our parliament and, laughing, told us not to be afraid of it, was also taking a holiday. Despite the unfolding catastrophe back home, he relaxed on Hawaii.

Australia is on the frontline of the climate emergency. We’re a hot, dry continent where climate change has long been predicted to wreak havoc. Ross Garnaut, a professor of economics, led the government Climate Change Review 12 years ago. It stated, prophetically:

“Fire seasons will start earlier, end slightly later, and generally be more intense. This effect increases over time but should be directly observable by 2020. The risk [of damaging climate change] can be substantially reduced by strong, effective and early action by all major economies. Australia will need to play its full proportionate part in global action. As one of the developed countries, its full part will be relatively large, and involve major early changes to established economic structure.”

Australia has not played its part. For decades, I have been proud to tell people I’m Australian. Invariably the reaction is positive. How they love Australia: Our landscape, our weird fauna, our people. Now I’m a little less cocky. On more recent travels, people have expressed dismay at our support for massive new coalmines and our plans to use accounting tricks to meet our Paris Agreement targets.

I, like many fellow Australians, was deeply embarrassed to see our Minister for Energy and Emissions Reduction torpedo last December’s climate negotiations in Madrid. This same minister, my local MP, who has never turned up to the launch of any of the multi-million dollar windfarms in his constituency, showed up at the re-opening of a coalmine here, closed for three days due to the bushfire threat. This minister who, on New Year’s Eve, the most destructive day of this fire season, wrote an opinion piece in The Australian newspaper, gloating about how well we were doing in combating climate change.

Our leaders tell us and the world we are doing our bit: We’re not. They say that given we’re “only” responsible for 1.3 per cent of global emissions, what’s the point of doing more than we have to? The fires this season will now more than double our annual emissions.

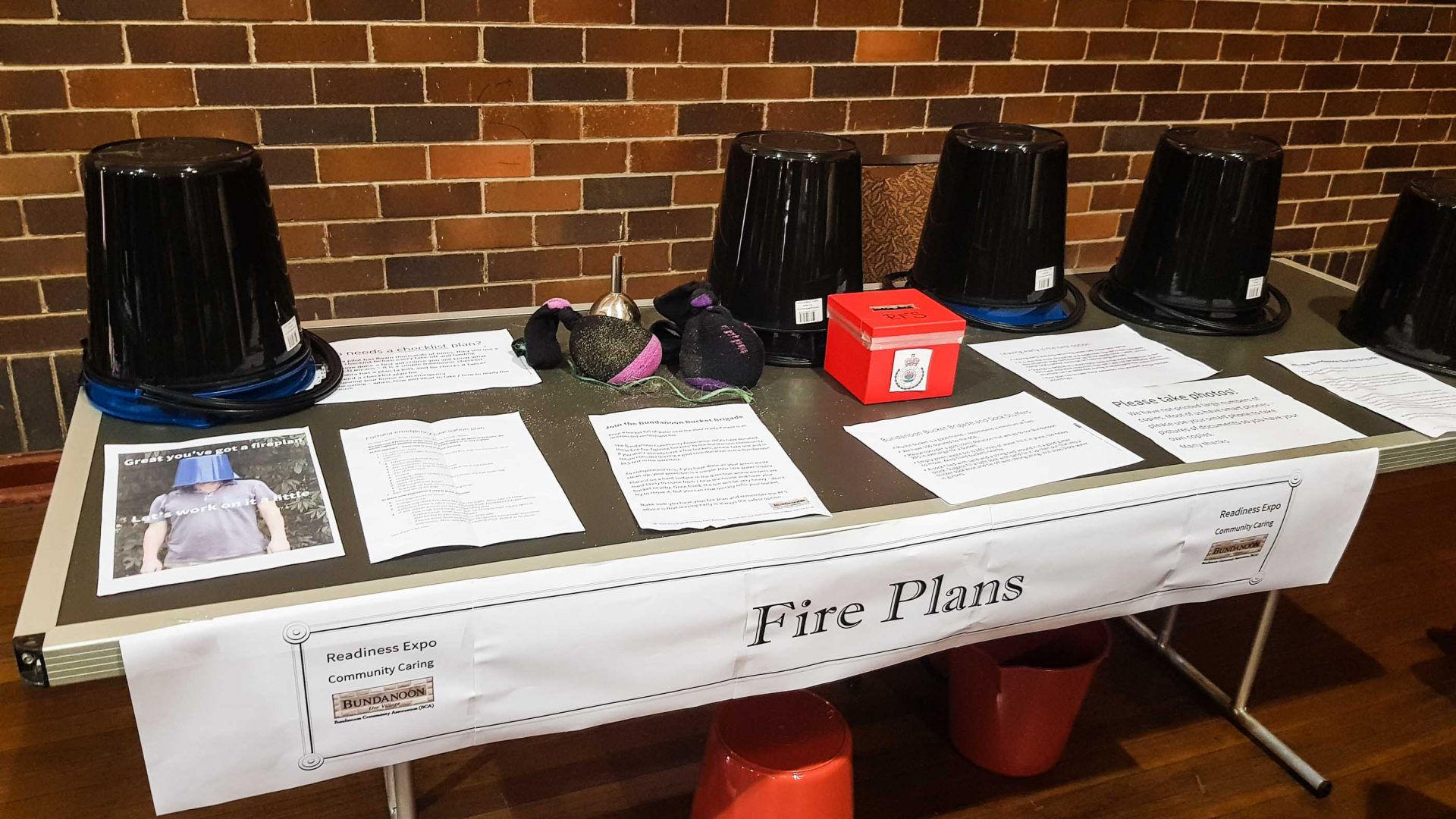

I spent the first days of 2020 removing trailers full of timber, leaf litter and more from our property and helping neighbors do the same. Hoses were checked and connected, downpipes blocked and gutters filled, wheelie bins filled with water, furniture removed from decks. Face masks, cotton clothing, woollen blankets, torches, radios were all prepared. Community meetings were held, fire plans written. Plans to stay and defend. Plans to leave. Sentimental, irreplaceable and valuable possessions were moved to places less threatened. Many people had already evacuated.

“Take shelter from the fire; it is too late to leave” screamed an SMS at 10.30pm. Townsfolk took this as their cue to go, largely because there had been no time to issue the expected first standard message (“If you plan to leave, leave now.”) Cars clogged the roads, exit routes were blocked by the fires, and U-turns were quickly made. Dozens of fire trucks poured into town.

RELATED: The best way to help during Australia’s historic drought? Visit.

By dawn, the damage could be counted. Somehow ‘only’ four houses had been destroyed in Bundanoon but our neighbors, in the little village of Wingello, had not been so fortunate, losing a dozen.

For the past month, despite hundreds of waterbombing sorties by helicopters, the fires have climbed over our back fence from the gullies to threaten, again and again. Each time, they have been beaten back by our formidable firefighters or halted by the welcome dying-off of a threatening wind. These fires are our neighbor now.

‘Leadership’ is making a stand. ‘Leadership’ is setting an example for the tens of other countries who “only” emit 1.3 per cent of emissions. ‘Leadership’ is showing the biggest polluters the economic and social benefits of taking meaningful action. ‘Leadership’ is something we sorely need in Australia this decade.

Is this the moment for my country to wake up or will we, once this apocalypse passes, slumber again in our comfort and inertia?

Australia’s abundant natural resources have made it one of the richest nations on earth. Materially, from mining them and spiritually, from our incredible landscapes. As we move warily into a new decade, we must turn away from the riches underground and instead to the renewable resources above: The wind, the sun, the tides, and our people.

––––

Postscript: A week after I wrote this article, much of eastern Australia was deluged with rain, the biggest falls in some years, on the same weekend as Storm Ciara wreaked havoc in Europe. We all rejoiced as up to 300mm hosed down fires, filled dams and drenched the parched land. Some of us can now relax. A little. The rain fell mainly along or close to the coast, leaving the inland still under the grip of the drought. It was good news indeed but no excuse for inaction.