Writer Peter Wilmoth has been heading to Bali for over 40 years. In that time, he’s seen Seminyak go from outpost to overtouristed, and watched the last rice paddies in towns disappear.

Writer Peter Wilmoth has been heading to Bali for over 40 years. In that time, he’s seen Seminyak go from outpost to overtouristed, and watched the last rice paddies in towns disappear.

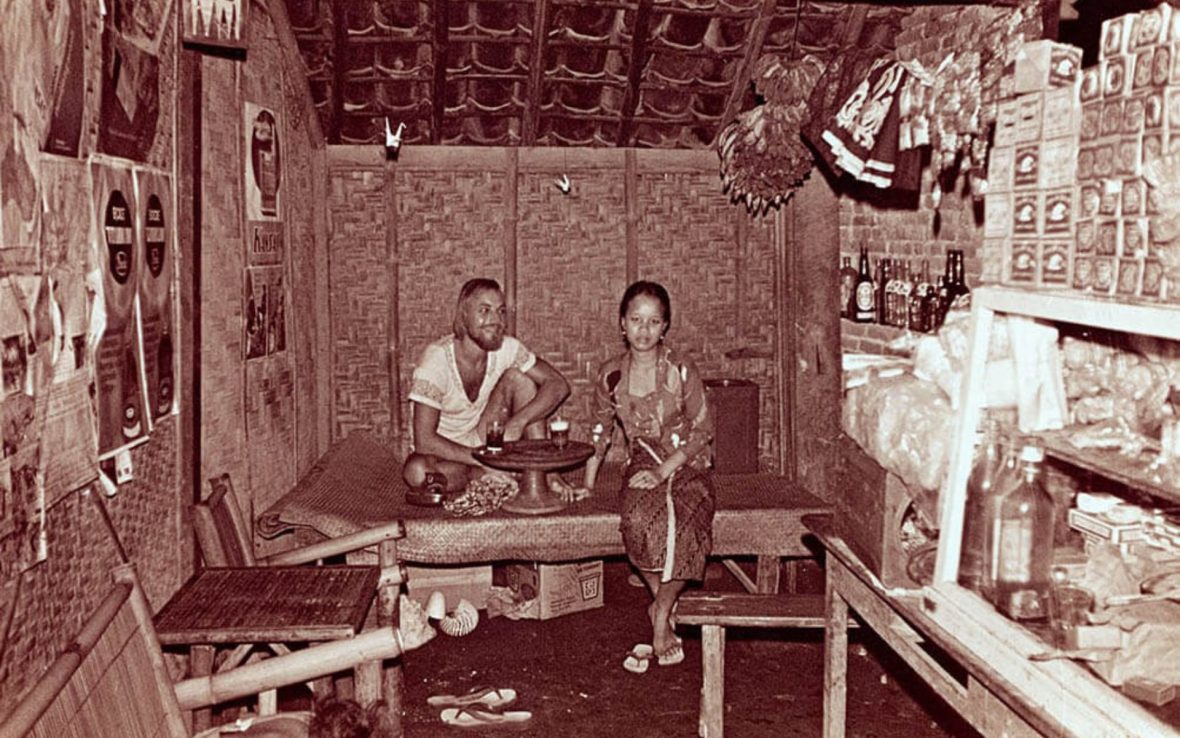

It’s a warm May evening in 1985 and I’m reading a book outside my losmen (a traditional guesthouse), shared with my friend Matt, no pool, USD$3 per night in Kuta, southern Bali. Clinging to the wall behind me is a gecko in full song. The air is redolent with frangipani, incense from the canang sari palm-leaf baskets placed on the ground as offerings to the gods, my Gudang Garam clove cigarette, and the industrial-strength mosquito repellent covering most of my body.

It’s my first trip to Asia and the first of what’s now probably 20 to Bali. It was a time of firsts: First time on a motorized scooter; first time in the tropics; first surf in the Indian Ocean; the pleasure of my first gado-gado (Indonesian salad). And each of these memories remain gin-clear in my mind.

Fast forward a few decades. This time it’s a June evening, earlier this year, and I’m eating at Mama San, my favorite restaurant in Seminyak, just a few miles up the road from Kuta. I’m sitting opposite that same Matt. We both have pricey cocktails in front of us, very different from the Bintang beers and occasional fiery arak (fermented rice or coconut flower sap) shots we drank together in the 80s.

After a six-year gap between visits—pandemic-related lockdowns explain some of that—I’d returned to Bali. I wanted to see if the magic of the island was still there in 2025, for me at least.

In 40 years, a lot has changed. Over 1.5 million Australians visited Bali in 2024, a huge jump from the 350,000 people who holidayed annually on the island in the ‘90s. Bali is to Australians what Cancun is for Americans or Benidorm is for Brits.

Nowadays, headlines include news of tourists behaving badly, terrible motorbike accidents, traffic gridlock and viral videos of disrespectful tourists, like the woman caught riding a motorbike without a helmet and arguing with the police over a USD$16 fine.

Some Australians now sneer at the decision to holiday in Bali. A friend sent me a farewell text before my departure: “Enjoy your end-of-season footy trip”. That one stung.

Kuta flowed into Legian, where Italian and Spanish travelers played beach soccer at dusk, before heading to sashimi dinners at Goa restaurant in Seminyak. To get from Kuta to Seminyak back then meant a bumpy motorbike ride past rice paddies and local warungs.

But as anyone who has ever wandered away from the sports and swim-up bars knows, Bali is not all Bintang-branded singlets and misbehaving Aussies.

And it certainly wasn’t in 1985. Making our way out of the glorified shed that was the international airport terminal, we were part of what could be called Bali’s second wave of Australian tourists—the Aussie surfers who came to Kuta and found incredible breaks off Bali’s southernmost tip in the late ’60s and early ’70s being the first.

By 1985, 15 or so years after these Aussie pioneers first paddled out, Kuta’s township had grown quickly. But it was still a cool place to be. Coffee was hard to find, but the best was at Kopi Warung (warung meaning family-owned restaurant) in Legian, a small coastal village north of Seminyak and south of Kuta. Breakfast was a banana pancake and lunch was roadside nasi campur (mixed rice with fried chicken or shrimp, boiled egg, sautéed vegetables and spicy sambal sauce).

Dinner was the big deal. It was often at Made’s Warung in Kuta, an uber-stylish diner and hangout with marble tables and black-and-white photos of early Bali hanging on the walls.

Made’s was a Bali trailblazer. It opened in 1969 as a small street stall and later became famous for its rijsttafel, an elaborate way of eating involving an array of side dishes in small portions created by the Dutch to showcase Indonesian food. Interestingly, I haven’t seen it on Bali menus since; I wonder whether this is due to its colonialist roots (the Dutch having colonized Indonesia in the early 1600s before recognizing its independence in 1949). But then it’s also been decades since I’ve seen turtle soup, which was everywhere in the ‘80s.

Made’s— still going today, you can even find one at the Denpasar airport—was where the action was. Cool types gathered every night with their silver bracelets, travel journals, clove cigarettes and studied nonchalance. A clutch of motorbikes sat outside, probably about to take them to Double Six nightclub where the beach party wound up around dawn. What a scene it was.

Kuta flowed into Legian, where Italian and Spanish travelers played beach soccer at dusk, before heading to sashimi dinners at Goa restaurant in Seminyak. To get from Kuta to Seminyak back then meant a bumpy motorbike ride past rice paddies and local warungs.

Seminyak was the outpost, still uncrowded and only slowly starting to attract foreigners. Similar to what Canggu, one of Bali’s more recent tourist zones, was a few years ago, with a growing community of cool travelers (don’t call them tourists!).

Things were simple. There were no social meda influencers, so we had to decide where to stay and eat all by ourselves. No-one photographed their food. The army of MacBook-wielding, kale smoothie-drinking, digital nomads were 15 years away from being born.

Some hangouts, which many Australians will recognize and may even remember with affection: The wall-less bedrooms at Three Brothers, a popular Legian budget hotel; sitting on the floor for pizza at Fat Yogi’s down Poppies Lane; The Living Room, a nightclub hangout in Legian; a surf at Echo Beach at the then untouristed Canggu followed by a bite at the memorably named warung, The Chew and Spew.

A name most visitors in the ‘80s and ‘90s knew well: The Sari Club. I dropped in occasionally, usually to meet up with friends to start the evening. After the tragedy of the Bali bombing terror attacks which happened there in 2002—killing 202 people, mostly foreign tourists—for those who frequented it, the poignancy and sadness will last forever.

But Bali has always bounced back from tragedy, even after a second terrorist attack at Jimbaran Beach resort in 2005. Tourist numbers soon reached record highs again, with Australians the most devoted annual visitors.

The vestiges of old Bali seem to have disappeared. I was walking in Seminyak several years ago and noticed a green rice paddy surrounded by hotels, shops and cafes. I remember wondering when the rampant development would consume what could be the last paddy in the city. On my next trip, it had been built over.

Forty years on, Seminyak—once an outpost—is now a party town. There’s a proliferation of tattoo shops. The roads can’t handle the traffic. Ubud, once a rainforest village, is now a hub for foreigners with wellness rituals.

But the beaches on the Bukit Peninsula remain extraordinary. One afternoon, I find a perch in a warung and watch surfers negotiate powerful six-to-eight-foot waves. They recover in wooden structures on the beach that seem like warungs, but I can’t see menus or waitstaff. They’re a million miles from Seminyak.

A couple of weeks after I returned to Australia, 48 restaurants on the beach at Bingin—deemed illegal by local authorities—were destroyed. Speculation is that the site will be re-developed as a luxury hotel. For me, it seemed another marker of change, not gradual but immediate and—to those who’d made their livelihoods there for 50 years—shocking.

The vestiges of old Bali seem to have disappeared. I was walking in Seminyak several years ago and noticed a green rice paddy surrounded by hotels, shops and cafes. I remember wondering when the rampant development would consume what could be the last paddy in the city. On my next trip, it had been built over.

My Bali anniversary has brought back cherished memories of discovery and friendship. It has reminded me how enchanting Bali is away from the touristed madness. It has also shown me how much Bali has changed in 40 years—how mass tourism has re-shaped the island, or at least the island’s southern parts, and led to rampant over-development.

Of course the magic is still there. It might just have moved up the coast a little.

****

Adventure.com strives to be a low-emissions travel publication. We are powered by, but editorially independent of, Intrepid Travel, the world’s largest travel B Corp, who help ensure Adventure.com maintains high standards of sustainability in our work and activities. You can visit our sustainability page or read our Contributor Impact Guidelines for more information.

Peter Wilmoth is a journalist and writer. He has written features for The Age, The Sunday Age, The Sydney Morning Herald, Good Weekend, The Weekend Australian magazine, Rolling Stone and The Weekly Review. He has written and co-authored several autobiographies including with cyclist Cadel Evans and footballer James Hird. He lives in Melbourne.

Can't find what you're looking for? Try using these tags: